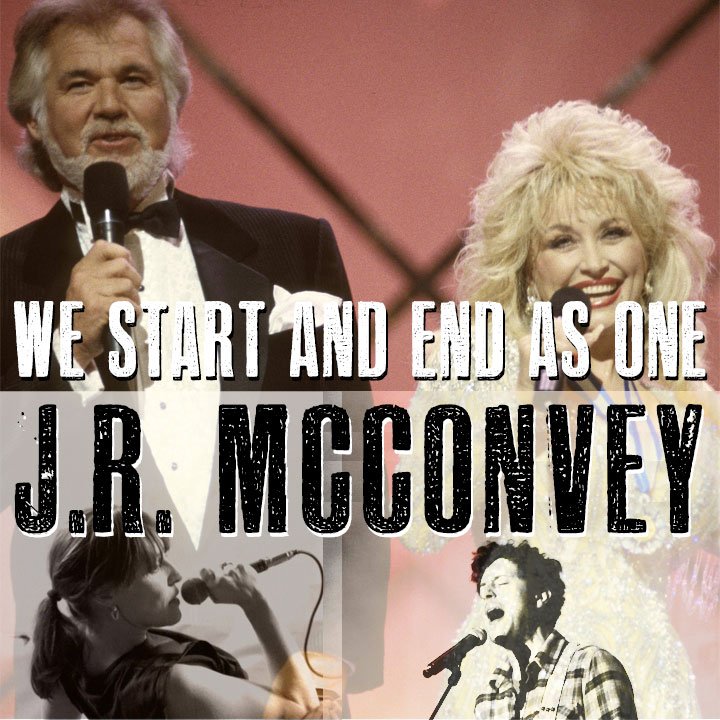

We start and end as one: Feist and Constantines covering “Islands in the Stream” by J.R. McConvey

This essay was supposed to be about the Cowboy Junkies’ cover of “Sweet Jane”. I mention this up front because, by establishing what it’s not about, I’m actually telling you what it is. If that sounds mixed up, it’s all in keeping with context. Some things—stories, songs, cities, countries—are destined to find definition in what they are not, perpetual reflections hovering at the edge of some bigger, more beloved thing.

I first heard “Islands in the Stream”, the chart-topping duet by Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers, in the living room of my childhood home, where my parents would dance around and sing the lyrics into candlesticks. I would have been three years old when it came out, so it likely counts among my first memories of music. The song was on high rotation on our record player, alongside other polished classics of Reagan-era American pop: Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark”, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”. The 80s was a decade of bombast, upward mobility, clearly defined enemies and computers that were still neat instead of essential, addictive or threatening. It’s an era many older Americans (and non-Americans) still idealize, the last moment before digital culture changed the world utterly. Kenny and Dolly were its perfect embodiments, beloved Nashville-bred country stars who crossed over into pop and exuded the wholesome, mainstream, red-white-and-blue patriotism that would come to undergird New Country.

Most of the music of my preteen years was made in and for the United States of America. I probably didn’t become aware of national difference in music until my teens, when I started listening to local rock radio, wherein it was a point of pride to play artists from Canada—even better if they were from Toronto (where I was born and still live). Even so, throughout the 1980s, Canadian music was a relatively modest affair; Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot already looked like folk relics, Neil Young had defected to California, and while Rush were among the most respected and popular rock acts of all time, they were (and remain) too easy to make fun of. Bryan Adams had some hits. So did Celine Dion. But a concrete sense of a thriving music industry and culture that was both distinct from America’s and successful internationally didn’t really emerge until after the millennium, with the establishment of the Polaris Music Prize and the ascendancy of Drake, Justin Bieber, Arcade Fire and—to a lesser but still culturally significant degree—Feist.

“Islands in the Stream” is a love song, but it’s a bit of a weird one. Kenny and Dolly’s buoyant delivery sells the tune as a proclamation of love as Fate, stronger than mere geography. But lines like “Baby, when I met you there was peace unknown” and “Everything is nothing if you got no one” play differently as a whisper—which is exactly what Feist and the Constantines offer on their 2008 cover version, released as a 7-inch single and later included as bonus content on the deluxe edition of Feist’s album, The Reminder. “No one in between,” sing Feist and the Cons’ Bry Webb, bleary with reverb; “How can we be wrong?”

Like the Cowboy Junkies’ “Sweet Jane”, “Islands in the Stream” plays like a melancholy echo of its upbeat original. Slowed down, the boomer-era optimistic sparkle replaced with indie-rock reflection, it exudes a sense of hushed, autumnal repose. The perky yacht rock groove is abandoned for a beat that sounds more like the breath of some big, lonely creature loping through the woods. The understory is a lovely low synth and vibraphone track (which, in researching this essay, I discovered was played by my friend, Paul Aucoin: Canada is huge; Canada is small). The love story within the song ages, becomes quiet but steady, with hints of sadness. The song is a sonic blanket, good for sitting by a crackling fire and staring into the starry distance—miles away from the breezy strut of its source material.

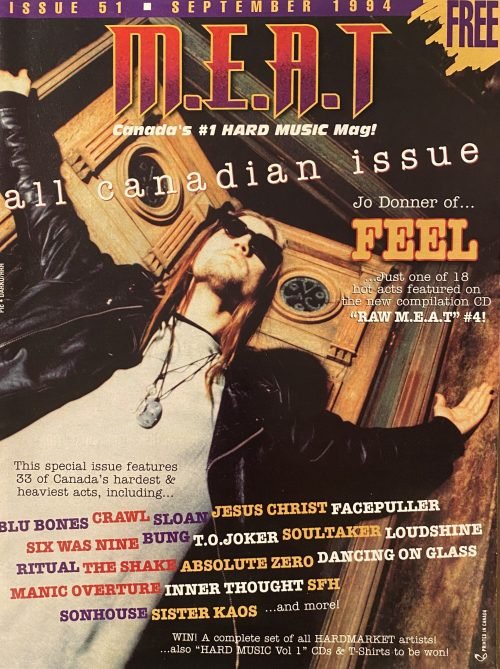

In the post-Drizzy era, when YouTube has obliterated traditional national borders for content distribution, it can be tough to convey how little cross-border love there was, for years, for Canadian music that deserved more attention. I remember sixth-grade talk about whether Maestro Fresh Wes, the godfather of Canadian hip hop, would catch trouble for declaring himself “not American” in his 1989 hit single, “Let Your Backbone Slide”. I remember M.E.A.T. magazine, a free metal rag published from 1989 to 1995, obsessing over who would be the next Canadian metal band to succeed down south.

The most famous band that never made it in the States is The Tragically Hip. It’s hard to describe the place this band occupies in Canadian culture, because there is no American equivalent. Part of the Hip’s appeal is that they couldn’t work in the U.S. marketplace. Legend tells of an L.A. record executive who, on hearing the Hip’s 1992 song, “Fifty Mission Cap”—an ode to Bill Barilko, a long-dead hockey player, and his would-be supernatural influence over the perennially bad Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team—suggested that it could be a smash hit, if anyone could figure out what the hell the singer was talking about. That singer, Gord Downie, is also gone now, felled by glioblastoma after a very emotional farewell concert tour that played, at times, like a religious ceremony. Downie was celebrated as much more than just a rock star. As the New York Times wrote in 2017, “Imagine Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Michael Stipe combined into one sensitive, oblique poet-philosopher, and you’re getting close” to what Downie represented to Canada. His cancer diagnosis and subsequent death received more coverage in U.S. media than the Hip ever got for their music.

When the band reunited earlier this year to perform at the Juno Awards (Canada’s Grammys), they chose, to step into Downie’s shoes, a singer-songwriter who had opened for the Hip on their 1999 tour, and whose reputation had since grown far beyond the 49th parallel—Leslie Feist.

Buoyed by Apple ads and an appearance on Sesame Street, Feist is now well known to U.S. music fans. Meanwhile, the Constantines, having gone on unofficial hiatus in 2009 and logging only a handful of reunion shows since, left behind only faint traces in the U.S., despite releasing their best album, 2003’s Shine a Light, on Sub Pop. They are the most exciting live band I’ve ever seen (for many Toronto rock fans my age, not a particularly controversial opinion): incredibly loud and energetic on stage and able to bring an audience fully and completely into a show. One of the most indelible concert moments of my life came during a Constantines performance at a stage by the Toronto waterfront, when, during the organ-borne breakdown of “Shine a Light”—which, by then, everybody knew meant you put your hands in the air—Bry Webb, his own hands aloft, said to the crowd, “Turn around.” As the band hammered back into the chorus, a volley of fireworks filled the sky in the near distance. It was Canada Day.

The Constantines’ hushed, relatively obscure cover of “Islands in the Stream” is, on account of Feist’s reach, probably among their most widely-heard things outside of Canada. It feels representative of how for many Canadian artists, the border is only semi-permeable. Even if you make it across, you’re likely to lose something on the way.

For the record, the most famous and well-known Canadian band of all time is probably The Band—who sang, with emphasis, about America.

“Islands in the Stream” was written by the Bee Gees, who are British by way of Australia—like Canada, a colony. When Barry Gibb wrote in the chorus, “Islands in the Stream, that is what we are… and we rely on each other, ah-ha,” he probably wasn’t thinking about colonialism, about cultural hegemony, about two entities existing as one, except with one part much larger and more dominant than the other. But it fits (though I have no explanation for why islands, in this metaphor or at all, are supposed to sail): islands are perfect for colonizing, for creating “another world.” “How can we be wrong?” is the colonizer’s rallying cry, committing casual atrocities in the name of God and country. Imperialist nations absorb other, smaller ones: “we rely on each other, ah-ha.” Still, we are lovers. Who does not wish to love and be love in returned by the gatekeepers of what has, for so long, been called paradise? Watching from across Lake Ontario, the present American predicament looks sad and dangerous. And yet, to give up on the U.S. and its project is to admit a hard defeat after centuries of effort, and to open a void that must be filled in its place.

The nation widely known as Canada has never been sure how to feel about itself. Two quotes resonate throughout decades of soul searching. The first is from Marshall McLuhan, who said that “Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.” The second comes from Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s 15th prime minister and father to our current one. Speaking in 1969 to the Washington Press Club, Trudeau likened existing beside the United States to “sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast… one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” To be Canadian is to have an innate case of impostor syndrome, to always feel bridesmaid over bride, to admit our smallness, caught between a giant of western enterprise and a northern wilderness larger than most of the world’s countries. Even if the U.S. falls from cultural dominance, replaced by some other behemoth, we will likely always live in America’s shadow, no matter how many streams Drake racks up. We are the rapper who croons, the anthem rendered as a quiet cover: we are what we are not.

Because what it means to be Canadian is so vague and fungible, much is still possible in terms of how we create a shared future. The cultural conversation these days is much about Indigenous peoples—“Truth and Reconciliation”, in the frame of the government. The fundamental question at play is how to manage a place in which the Indigenous cultures that were erased by colonization can be brought back, within the reality of a modern urban society that is not going to disappear. Political discussions to date have been slow. There is much justified distrust to overcome.

Musically, however, the conversation is more fruitful. It has room for artists like Snotty Nose Rez Kids, Jeremy Dutcher and Crown Lands, all of whom mix elements from their Indigenous traditions with western musical forms. It also loops in Backxwash, a Zambian-Canadian artist whose music mixes hardcore rap, metal and an aesthetic of gothic suffering to speak to issues around gender, race and outsiderness. Both Backxwash and Dutcher have won the $50,000 Polaris Prize, significantly boosting their profile; Dutcher, whose process involves creating duets with old wax cylinder recordings of songs sung in the Wolastoqiyik language as a way to keep it alive, recently appeared on the new album from the world’s most famous cellist, Yo-Yo Ma.

These artists are, if anything, emphatically not-Canadian, dealing in reimagined ideas about what the country should be at this moment in time. America hardly comes into the picture. It’s fitting that the next wave of culturally distinctive music coming out of Canada exists to interrogate it, to be yet another negation. Canada was a cover song to begin with, an attempt to build a mirror of Britain overtop of a society that was already there. Over the last century, our culture has often looked like an afterimage of America’s. We have switched partners, and the arrangement has not always been formal, but it has always been clear: we start and end as one.

Now, however, there are other views at play. There are those that would point not to the islands—eroding, at odds, swept with ominous winds—but instead to the stream. There is something between, after all.

This has gotten away from Feist and the Constantines covering Kenny and Dolly. But that’s fine. It was never really about that, anyway.

*

A few doubly Canadian covers:

Barenaked Ladies cover Bruce Cockburn’s “Lovers in a Dangerous Time”:

k.d. lang covers Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”:

The Rheostatics cover Gordon Lightfoot’s “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”:

Enjoy!

J.R. McConvey’s debut short story collection, Different Beasts (Goose Lane Editions), won the 2020 Kobo Emerging Writer Prize for speculative fiction. His stories have been shortlisted for the Journey Prize, the Bristol Short Story Prize and the Thomas Morton Prize, and published widely in magazines and anthologies. He is also a media producer whose work includes The National Parks Project, a series featuring 39 Canadian musicians you’ve maybe heard of. He exists online @jrmcconvey and jrmcconvey.com, and in physical space near Toronto, Canada.