(6) Gary Numan, “Cars”

DOUSED

(10) Midnight Oil, “Beds are Burning”

280-247

AND WILL PLAY IN THE ELITE 8

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/22/23.

Cars on Alternate Earths: elana levin on “cars”

Here in my car

I feel safest of all

I was a young teen the first time I heard Gary Numan’s hit song “Cars.” The best friend of my penpal/zinester friend had made her a beautifully constructed mix tape of 80’s New Wave. She loved it so much she sent a copy of it to me. The mix was my gateway to appreciating synth-led music. I’d previously found synths corny because I associated them with the overplayed, overproduced pop music I’d thoroughly rejected as a solidly counter-culture teen. But Gary Numan was different.

It was the mid-90’s and yet this 80’s New Wave music still sounded like science fiction. What I could not have known at the time, was that while Gary Numan may have been singing to me from the past, he was predicting my future.

I can lock all my doors

It's the only way to live in cars

Hearing the song as a teen the idea of people locked away in their solitary cars felt completely pitiful and bizarre to me. I didn’t have a driver's license. I never got one. I grew up in the DC suburbs but we lived along mass transit lines. I’d grab my walkman and walk, or take the bus, or Metro (or get a lift from a friend). I felt like I was part of the physical world around me.

A lot of drivers describe their car as their fortress. Numan, speaking of the road rage incident that inspired Cars, said “I began to think of the car as a tank for civilians”. Yet statistically speaking, cars have been one of the more dangerous modes of transportation for pedestrians and drivers alike.

Here in my car

where the image breaks down

Numan’s protagonist wasn’t wrong. He was just ahead of his time. A highly contagious airborne virus has changed the safety equation. The risks of riding in a car and the alienation it creates are the same as ever but being in a bus or train full of unmasked people is an easy way to catch COVID. So now instead of riding mass transit with others I’m in a private car. Numan’s sci-fi dystopia has come to pass for me.

Did it have to be this way? Like much of Numan’s repertoire, “Cars” is a work of speculative fiction. So let’s speculate on some parallel worlds. DC Comics gives us a naming convention for parallel worlds, Earth 1 and Earth 2. Here we can explore the different possibilities of how music is spread and how a novel airborne disease is communicated.

Art by Jerry Ordway

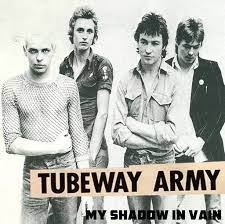

On our Earth (let’s call it Earth 1) Gary Numan’s punk band Tubeway Army was recording in Cambridge England at Gooseberry Studios. On Earth 1 a band whose name was lost to history accidentally left a minimoog synthesizer behind in that studio. As soon as young Gary got his hands on this technological device he was fully committed to making synth-led music. His label expected a more traditional punk album, but by 1979 Tubeway Army released their groundbreaking second album Replicas, which birthed the sound that would make Gary Numan famous.

Like any superhero, Gary Anthony James Webb renamed himself after discovering his musical powers. He called himself Gary Numan. New Man. The man of the future. This man of the future’s music was era-defining and so compelling that teens like me who were barely alive when it was recorded were trading it on magnetic cassette tapes to listen to on the train 15 years later.

In some parallel earth (let's call it Earth 2) Gary Numan’s punk band Tubeway Army recorded their debut album in a studio in London. They don’t find an errant synth in the studio. They go on to record some good songs: you can hear one of their more straight-ahead punk songs here:

It’s good punk rock but it certainly is not groundbreaking like “Cars,” which should be the rightful winner of this March Fadness bracket.

Here on Earth 1 Numan decided to try his hand at bass. He’d never played bass before but he bought one and brought it straight to the studio. The first notes he played on the first bass guitar he ever held, was the riff that formed “Cars.".

Our Gary Numan says “Without a doubt, those were the most productive eight minutes of my entire life”. The result was his only mainstream US hit.

On Earth 2 Gary Numan stuck to playing the guitar. Earth 2 Gary Numan probably wore brighter colors and possibly eschewed that platinum blond moment that our Gary had. Maybe he played guitar solos. Statistically, he was probably not going to write a watershed breakout single.

Music historian Andrew Hickey always says “there’s never a first anything” in music but “Cars” was pivotal in popularizing the use of synth as a leading instrument in pop music. Before, synths were either a novelty instrument as in Runaway by Del Shanon, or if they were more central it was in avant-garde music like Kraftwerk or side 2 of Bowie’s Low, or mixed somewhere in a Pink Floyd trance. In Gary Numan’s music the synth is the star of the show and the show is general admission.

Cars was the birth of synth pop. If you love Depeche Mode, Erasure, Nine Inch Nails, CHVRCHES—give Gary your vote.

“Cars” is extremely catchy. You can hum it. And you can dance to it. Of course it became a hit. But it’s also extremely weird. It doesn’t follow a standard pop song structure. There’s a synth and tambourine solo where the guitar solo would be. The outro is lengthy. The protagonist is not a cool or aspirational figure. He is an outsider inside of a car.

As a young teen a psychologist told Numan he suspected he had “Aspergers” as they called his form of Autism at the time. For many years now Numan has spoken frequently about being autistic, its impact on his art and his experience of being in therapy as a child. Cars is a song by an outsider for outsiders.

During an era of social distancing the synth becomes the perfect instrument: it's a band you can be in all by yourself.

The only instruments in Cars are synth, distorted bass and percussion–which includes that rattling tambourine—like a ball bearing broke loose in a factory. The synth makes a wobble like sheet metal pounded thin. The riff takes that quavering sliver of metal, clones it, stamps it into shape and shuffles each copy away in a metal filing cabinet.

Numan’s nasal monotone vocals are double tracked. It makes the thin sound fat. A single, unique singing voice becomes an army of Numanoid clones. And there would be clones….

Here in my car

I can only receive

I can listen to you

Calling Numan a “one hit wonder" because he only had one single reach the US Hot 100 Singles Chart makes as much sense as calling Lou Reed a “one hit wonder”. Lou holds the same chart statistic as Numan. No one doubts Reed’s influence.

But there is a conversation to be had around how influential “Cars” was in reshaping popular music that came after, including that of a lot of popular artists who would come to dominate the charts and be generally more commercial, and often less inventive. You can hear Numan’s influence in many other songs on this bracket like “She Blinded Me With Science,” “Relax,” and “It’s My Life.” His hand is certainly all over the Goth and Industrial music I danced to as a teen and college student taking the train– not a car—to clubs in DC and NYC.

Numan has said Cars is awkward to perform live as there’s not much to sing.

The song doesn’t follow popular music’s standard verse chorus verse chorus structure. During the instrumental stretches all he has left to do is shake the tambourine and look into the vastness of the replicant army. Numan is handsome but the way he presented himself on TV when he performed was cold, removed, synthetic, anti-charismatic but completely compelling.

Because Earth 2’s Tubeway Army never lucked into a synthesizer and remained a standard punk band they never reached the greatness that is Gary Numan’s solo career. Yet the Earth 2 band would probably still be good enough that alternate earth Elana would want to see them play Le Poisson Rouge in 2023.

But this is Earth 1—we may have the best Gary Numan but we’re in the throes of an ongoing global pandemic and our public health infrastructure might as well be from Star Trek’s evil Mirrorverse or DC Comics evil reality, Earth 3.

I doubt I’ll be able to go to see Numan’s big tour. I caught COVID in December and I’m not fully recovered yet. I can’t risk catching it at a concert. But Gary Numan is ever a Futurist. He’s offering an online concert for the reasonable price of €6 or $6.50 for a 7 day rental. Technology like this helps us avoid the virus. We can even watch together remotely, live chatting and streaming together.

I can listen to you

It keeps me stable for days

On Earth 1, for the first time in my life the safest way for me to get somewhere is in our private car. Driving itself didn’t get safer, but COVID and the end of mask mandates on public transit changed the math of Earth 1 and changed my body.

As I write this in February I’m still struggling with the after effects of my “mild” case of COVID. For now I am unable to do some of the things I rely on, like walking everywhere. With too much activity I get vertigo and migraines. This never happened before. It should pass but for many who suffer from Long Covid it doesn’t.

I’d been privileged enough to avoid catching COVID for a long time. When I got it in December it was either outside at a holiday market or while I was wearing an N95 mask in a public bathroom. If COVID exists on other earths Elana certainly wouldn’t catch it that way. Maybe if COVID hits other earths they would require masks while spread is high (some places here do still require masks).

Art by Carmine Infantino & Murphy Anderson,

The ruling class knows what it takes to make shared spaces safe: air filtration, UV light, PCR tests and N95 masks. They’re demanding it and getting it. If enough people unite to demand a real public health response from institutions on this earth, we could safely gather too.

But without any mitigations it's far too easy to catch a disabling disease on mass transit. Or at a show. In all those places I used to love and felt safe in.

When the pandemic began, walking went from being one of the options I enjoyed to being my only escape. I’d put my headphones on and log more steps than ever before. Now that I’ve had COVID I can’t even do that anymore.

The song “Cars” is a sympathetic critique of the isolation created by our fear of being vulnerable. But isolation is one of my greatest fears. As an extrovert who also can’t afford to be sick, COVID has been emotionally exhausting and frequently isolating.

Now in the fourth year of the global pandemic so often my spouse and I are stuck as a unit of two in our private car. One thing we can control is the stereo.

Will you visit me, please

If I open my door in cars?

If you want to ride with us we can all don N95 masks and open the windows for air circulation. We will look like we’re from the future. Share playlists instead of mix tapes. You won’t see half my face but we won’t be alone, and we won’t be forcing others to be alone either.

Elana Levin podcasts at the intersection of comics, geek culture and politics as Graphic Policy Radio and Deep Space Dive: a Star Trek Deep Space Nine Podcast. Elana’s critical work has appeared in The Daily Beast, Wired Magazine, BBC Radio, Graphic Policy, and Comics Beat and more. Elana enjoys explaining why Hair Metal is actually camp on the finest music podcasts and in March Badnesses. Elana is @Elana_Brooklyn on “the socials" and teaches digital strategy to progressive campaigns and nonprofits.

KEITH PILLE ON “BEDS ARE BURNING”

1. THE SONG ITSELF

It’s incongruous that this song is even on this list. It’s a freak fact, an artifact of the top 40 charts; to classify Midnight Oil with Taco feels like a category error. If you were a young musichead in the late 80s and early 90s, Midnight Oil were an immensity you had to reckon with. When Blue Sky Mining came out in 1990, it was a major event that we all anticipated and luxuriated in; I remember MTV going into one of their occasional “this is an album YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT!” cycles. And it was a major event, of course, because the success of 1987’s Diesel and Dust and its breakout single “Beds Are Burning” put us all on notice that this was a band to keep an eye on.

And there’s the rub. “Beds Are Burning” was a pretty big crossover hit. In the normal course of things, Midnight Oil were giants within the fevered niche of what we then called alternative rock and absolutely unknown outside of it. This one song, soaring on the fact that it fucking rocked and carried an urgent message (probably leaning harder on the “fucking rocked” side) crossed over out of the alt-rock world and into the top 40. Viewed from within the alt-rock world (and the successor “indie rock” world most readers of this tourney inhabit these days), Midnight Oil were titans; but viewed from within the top 40, they were a weird band who had one modest hit. It’s that Kenobi thing: many of the truths we cling to depend entirely on one’s point of view.

Back to the fact that the song fucking rocks; we wouldn’t care about it so much if it didn’t. It opens big: BAH-BAH BAAAMP! The horn stabs! A brief quiet pause, and then the rhythm section gets rolling. The bass and drums on this song are something to marvel at (when I brought this song into a bass lesson in high school, the slippery Peter Gunn thing they have going on absolutely defeated my teacher, who was otherwise peerless at working out parts for songs I brought in). They kick into a chugging, ticking engine that manages to sound organic and mechanistic at the same time. A heart, maybe?

Peter Garrett starts singing; it’s a singular voice, quavering and close to monotone (in the early going, he’s just moving between a few notes) but also somehow authoritative. And he’s telling us a story! “Out where the river broke…”

I don’t want to turn this into a livetweet of walking through the song; you can (and should!) listen to it and decide if it clicks for you. I just want to establish that it grabs your attention upfront and holds it throughout. And that it’s produced in a way that doesn’t much like anything else we were hearing back in 1987. Again, this thing opens with horn stabs that serve as a repeated hook through the song. The instrumental production is wide-open, clean and spacious, and it kind of has to be because there are a *lot* of instruments competing here: the aforementioned bass and drum parts, those recurring horns (including what sounds like a French horn taking a solo! Let me be clear: you do not hear a lot of French horn solos in rock and roll), synths, guitars, Peter Garrett’s voice (often multitracked). The balance of “there’s a lot going on here” and “but it’s produced so cleanly that none of it clashes” makes one think of late Pink Floyd, except that instead of indulgent and overwrought, this one’s just sincere and good.

In the absence of all context, this song is good on its own merits. But nothing exists without context; and there’s all kinds of interesting stuff here at different levels of focus.

2. PERSONAL CONTEXT: THE AUSTRALIAN THING

In the late 1930s, my grandfather was a baseball prospect in central Iowa; a scout from the Cubs invited him to come to Chicago to try out. But his father nixed the trip because he needed all of the help he could get on the hog farm, and the chance passed (the Cubs would subsequently take 77 years to win a World Series. Connection? You decide). A couple of years later, my grandfather was drafted into the US Army Air Corps and stationed in Australia, where he fixed planes, played baseball for a team in Sydney for a few years (family legend, which I want to believe but can’t really commit to, has it that he was called the “Lou Gehrig of Australian baseball”), and wooed a girl from Brisbane, who he eventually brought back to the American Midwest and had 11 kids with.

What this means is that growing up I (and all of my many aunts, uncles, and cousins) always had this weird Australian identity thing going on where, like of course we were American and GO USA! but also we were pretty into Australia and being Australian. This meant watching Crocodile Dundee a *lot* more than was really necessary, but it also meant being hipped to the fact that Australia really seemed to punch above its weight, population-wise, in terms of producing cool music. AC/DC, Men at Work, INXS; all bands I could feel a shiver of “they’re on *my* team” pride whenever I heard them on the radio.

And of course Midnight Oil was part of that pantheon, as I was sliding from listening to whatever the Omaha classic rock radio station happened to be playing to listening to stuff *I* was choosing on tape. But Midnight Oil was different from all of the other Australian bands. AC/DC ruled, but they were gloriously dumb (this was, in fact, part of why they ruled). Men at Work weren’t dumb, but they felt slight (maybe they shouldn’t have, given how heavy a song like “It’s a Mistake” is, but at the very least their production made them sound slight). INXS, it still pains me to admit, were really pretty close to as gloriously dumb as AC/DC, just presenting it in much more stylish wrapping (I say this not to shit on them; they rule. But most of their songs are written from the point of view of Michael Hutchence’s junk). Midnight Oil, on top of rocking, were clearly not dumb. They sounded really smart, and they had stuff to say. Stuff to say about important topics. This seemed especially big in the late 80s, when R.E.M. and U2 (and more on them in a moment) were establishing that to be a capital-letter Important Band you had to have stuff to say about important topics.

3. MUSIC SCENE CONTEXT: THE RIGHT HONORABLE PETER GARRETT

The one giving voice to all that stuff to say about important topics, of course, was Peter Garrett, the band’s lead singer. Garrett fascinated me in 1987 and he fascinates me now. His voice, as I mentioned, is distinctive, and his point of view doubly so. But so is his physical presence: six and a half feet tall, skin bald, athletically built, and given to dancing in a way that wasn’t that unlike Martin Short’s comic character Ed Grimley. Midnight Oil videos used him to great effect; consider how often the video for this song is content to show him in silhouette, knowing that this is as arresting a visual as they need.

But let’s back up and talk about his point of view. It was taken as a given in the late 80s and early 90s that Important Bands must, as a condition of their importance, weigh in on the political matters of the day (I remember a sad conversation where a friend and I, acting as the world’s lamest revolutionary tribunal, concluded that it wasn’t OK to like Soul Asylum because they put too much energy into trying to be funny and not enough into making the world a better place). R.E.M. did it. U2 did it. Midnight Oil did it (foregrounding indigenous concerns in a way most of their peers didn’t, which we’ll be circling back to before long). But over the long haul, Garrett took a step further than pretty much any of his 80s alternative-rock peers: he stepped down off the stage and got in the actual fucking game.

Garrett served two stints as the President of the Australian Conservation Foundation, from ‘89 to ‘93 and then ‘98 to ‘02 (this means that he managed to kick absolute ass on Blue Sky Mining while in office), with a term on the international board of Greenpeace sandwiched in the middle there. In 2004, he was elected as a Labor Party member of the Australian House of Representatives, and was subsequently named Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts and then Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth, eventually leaving government in 2016.

I’m not plugged into Australian politics well enough (or at all, really) to know if Garrett was effective in these posts; knowing the nature of politics, I’m sure he accomplished some things but was often hemmed in by larger structural forces. He no doubt had to compromise frequently in a way that doesn’t live up to the rhetoric you can drop from a stage. But I’m absolutely in awe of the fact that he got into the game. As much as I respect Michael Stipe, he was never willing to go that far to back his words with action (as far as I can tell, the most politically active member of R.E.M. seems to be Mike Mills, who to this day still does absolute yeoman’s work owning reactionary dickheads on twitter; activism can take many forms). And it’s a damn sight better than the empty posturing of Bono, who yammered endlessly about liberal causes while doing photo ops with George W. Bush and later turning up as a lunch partner in Jared fucking Kushner’s memoir.

I’m reminded of a bit in Tom Perrotta’s Election when student Lisa Flanagan asks Mr. McAllister why the pundit George Will never actually ran for office, and McAllister dismissively says that a knob like Will knows deep down that he’d get smeared if he ever had the guts to actually try to put any of his opinions into practice. Bono reeks of George Will here; Garrett had the guts to wade into the fray.

4. POLITICAL CONTEXT: IT BELONGS TO THEM

I keep mentioning that the song has important stuff to say. Let’s circle back to that.

For listeners who aren’t listening to more than the chorus (especially people who aren’t super imprinted onto the video), I think the song could land as a not terribly specific statement of urgency: how can we dance when our world keeps turning? How can we sleep while our beds our burning? These are great lines on their own, and they could easily attach themselves to any situation that’s in need of urgent action. In 2023, if you heard them without context, you’d think they were talking about climate change.

But they’re not. Australia is a land whose current residents are predominantly made up of descendants of Europeans who moved in and displaced or outright removed the people who’d previously been living there. This was an ugly process that involved a mix of outright murder and theft mixed with land-transfer agreements negotiated in bad faith by the Europeans. The members of Midnight Oil, touring through the Australian backcountry, saw the conditions that members of Australia’s indigenous people were experiencing, and it made them angry. Hence this song. The time has come to say fair’s fair. To pay the rent, to pay our share. In other words, at the very least, honor the fucking agreements, stop the ongoing exploitative behavior, and try to remediate what’s already been done.

I said earlier that I’m not plugged in enough to Australian politics to know if Peter Garrett was any good as a politician; along the same lines, I’m not conversant enough in Australian history and racial politics to catch all of the nuances in this song. But here’s the thing: I don’t really have to be to get the emotional drift, because the United States is every bit as much a case of Europeans moving in and stealing an entire continent. In the US (and I would be shocked to learn that it’s very different in Australia), the standard line is that well, that all happened long ago, what’s done is done, everything’s OK now; you only have to be minimally aware of the news to know that this isn’t the case. Oil companies are allowed again and again by the government to build pipelines across native lands, over the protests of tribal governments who say—rightly—that oil pipelines leak all the time and the leaks will put petroleum straight into their water supply. It’s a crock of shit, and it needs to stop. Honor the fucking agreements. Stop the ongoing exploitative behavior. Try to remediate what’s already been done. The song resonates because the problems it speaks to are both very specific and depressingly widespread and timeless.

It's worth asking: is it right for a bunch of white musicians to write a song that tries to give voice to indigenous communities? And that’s not a thing I can answer with much of a rhetorical leg to stand on, being a white person myself (and one from another country at that). It would have been wonderful if there had been an Indigenous Australian band in a position to have a hit singing about the shit deal they’d been given. But the structure of the music industry, especially in 1987, all but precluded such a thing. In the meantime, Midnight Oil was there and did have a platform. To me, at least, this song does feel like a sincere effort made in good faith; Garrett and the Oils (that’s what we hep insiders call them, by the way) never claim in this song to speak for indigenous Australians. The song’s lyrics are constructed to clearly always be colonizers addressing other colonizers: “it belongs to THEM, WE’VE gotta give it back.”

God knows that white people trying to involve themselves in indigenous concerns can go very badly; more often than not, it winds up feeling like their (our?) point is just to center themselves. “Stay in your lane” is a common piece of advice for a reason (and a quick aside here: “The Dead Heart,” another Diesel and Dust track, is written from a Native point of view and did draw criticism for it, especially for furthering a “primitive” stereotype; the band eventually decreed that all royalties from that song be given to indigenous groups, which was probably the right thing to do but also does feel like a lame after-the-fact “oopsie!” response). On the other hand, if you have a platform with a lot of visibility, and a chance to elevate an issue that you sincerely care about, maybe it’s not a bad thing to try to put the spotlight on it, in a way that doesn’t make you the main character? As an American, I’m much more conscious of Australian indigenous issues than I otherwise would have been, thanks to the music of Midnight Oil, especially this song. That has to be worth something. On the other hand, it’s arguable that not much in the way of actual real-world improvement has happened because of that consciousness, which I guess should factor into exactly how much it’s worth. On the other other hand (we Australian-Americans are known for often having three hands), that awareness has undoubtedly filtered over into the way I view American Indigenous issues, in a political sphere where I theoretically do have some minute influence as a voter, donor, and general loudmouth. Who knows? Advocacy is a land of contrasts.

Again, if the song’s concerns transcend the specific and move up to the general, in 2023 America “Beds Are Burning” always makes me think of the Land Back movement. I can’t pretend to know every detail of the Land Back program; and I have to imagine that, as with any large movement, you’re going to hear widely different goals and methods depending on who you ask. But what I understand as the basic goal—return lands that, per existing agreements, should belong to tribal nations back to those nations (the Black Hills being a prime example)—just seems like the morally correct thing to do. Honor the fucking agreements. Stop the ongoing exploitative behavior. Try to remediate what’s already been done. At the very least, have the conversation and move the Overton Window.

Two summers ago, in northern Minnesota near some tribal land, I saw graffiti on a rail bridge that made me think of “Beds Are Burning.” It said “WHITE PEOPLE: THIS IS OUR LAND. BUT WE’LL LET YOU STAY HERE IF YOU TREAT IT NICE.” It feels like we should be able to do a little more than that, but that seems like a good starting place at least. The time has come; a fact’s a fact.

Keith Pille lives in Minneapolis, unless he has frozen to death by the time this essay has run. Assuming he is not currently entombed in a block of ice, he writes articles and newsletters, draws cartoons, and makes podcasts (one about music, one about sea monsters). He shares his ice cave with his collage artist wife and a comically huge dog.