first round

(14) Tom Tom Club, “genius of love”

outsmarted

(3) Joey Scarbury, “believe it or not (theme from the greatest american hero)”

285-158

and will play on in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/4/23.

joyce millman on the “Believe it or Not (Theme from The Greatest American Hero)”

Full disclosure: The only reason I chose “Theme from The Greatest American Hero (Believe It or Not)” by Joey Scarbury as my March Fadness song was so I could write about its second life as one of the Top Five George Costanza moments on Seinfeld. As someone who’s obsessed, probably to an unhealthy degree, with the greatest sitcom of all time, my Costanza Rating reads as follows: 1.) Jerk Store, 2.) “The sea was angry that day my friends …”, 3.) The Trifecta, 4.) “Believe It or Not” answering machine message, and, 5.) “I was in the pool!”. But more on George later.

“Theme from The Greatest American Hero (Believe It or Not)” was written by prolific TV theme song composer Mike Post (with lyrics by Stephen Geyer) for an ABC superhero series that debuted in 1981. Post’s credits (some as co-writer) over the past four decades include themes for The Rockford Files, Magnum P.I., Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law, The A-Team and Quantum Leap. He also composed the signature “dun-dun” sound effect for Law & Order.

Post’s theme songs were everywhere in the ‘80’s. You couldn’t go into a dental office or a department store or be put on musical hold without hearing one of his tunes on a soft rock radio station or Muzak loop. And whenever you did hear one, it got you thinking about the previous week’s episode of L.A. Law, or made you want to track down a rerun of Rockford. That’s the best measure of Post’s work—his themes so deftly ushered you into the world of their shows that it was slightly disorienting when you heard one of these songs in the wild, as if your TV room was suddenly conjured out of thin air.

“Believe It or Not” was released as a single soon after the premiere of The Greatest American Hero; it also appeared on Joey Scarbury’s only album “America’s Greatest Hero.” It was the highest-charting single for both Scarbury and Post (who also produced it), reaching number two on Billboard’s Hot 100 and number three on the Adult Contemporary chart for the week of Aug. 15, 1981. It was also an anomaly: it was one of the few Post theme songs that wasn’t an instrumental.

“Believe It or Not” was a syrupy soft rock number that nestled comfortably in a Billboard Hot 100 teeming with snoozy hits by Air Supply, Pablo Cruise, Gino Vannelli, Jefferson Starship, Climax Blues Band and the like. As a music critic at the time, I regarded all of these easy listening tunes as pablum for the old at heart; I still stand by that assessment, even as the whole genre has now been rebranded as “yacht rock.” I do concede, though, that “Believe It or Not” has a damnably spirit-lifting melody on the chorus, with lyrics dopy enough to stick in your brain for all the wrong reasons: “Believe it or not, I’m walking on air/ I never thought I could feel so free/ Flying away on a wing and a prayer/ Who could it be? / Believe it or not, it's just me.” I mean, that out-of-left-field “who could it be?” line, and Scarbury’s earnest crooning of it, was destined for parody someday. The song sounded hopelessly dated and bland up against the sophisticated, sly pop of “Jessie’s Girl” by Rick Springfield and “You Make My Dreams” by Hall & Oates, to name two of its chart-mates. There was no way this song was ever going to age well.

And that’s okay, because the sole purpose of “Believe It or Not” was to convey the vibe of The Greatest American Hero in a way that would resonate with the series’ intended viewers, and anything it accomplished beyond that (like becoming a hit single) was an accident. Unfortunately, the vibe of the show was, as we used to say, unhip. The show (created by Stephen J. Cannell) was a superhero/sci-fi/comedy/drama about an L.A. teacher named Ralph Hinkley (played by William Katt) who has an encounter with aliens, during which they give him a suit with superhuman injustice-fighting powers. A sample of its humor: Klutzy Ralph repeatedly falling out of the sky because he lost the instructions to the suit and couldn’t master the art of landing. Beloved by younger brothers and sisters, The Greatest American Hero was filled with low-fi special effects that played as either awesome or cheesy, depending on your age.

The Greatest American Hero was old-fashioned escapism a family could watch together. Accordingly, the theme song was wholesome and retrograde, buoyed by Scarbury’s pleasant, if generic, tenor and an overpowering, musty assault of violins. Mind-blowing factoid: Larry Carlton, the cream of 1970’s and ‘80’s L.A. session guitarists, is also on the track. Carlton was a regular Steely Dan sideman (he played the revered, technicolor head-rush of a guitar solo on “Kid Charlemagne”), and finding him on “Believe It or Not” is like finding the Crown Jewels in a Cracker-Jack box.

The Greatest American Hero lasted only three unheralded seasons (two of them shortened), a relative blip in TV history. Its theme song might have also stayed in the land of dusty one-hit-wonder memories, if not for a turn of events as fantastical as Ralph Hinkley’s alien encounter. Comedy scriptwriter David Mandel was working on an episode of Seinfeld which included a scene where viewers are supposed to hear George Costanza’s outgoing answering machine message. Mandel remembered a friend singing “Believe It or Not” as an answering machine message and worked it into his script for the season eight episode “The Susie,” which first aired on NBC on Feb. 13, 1997.

In one of the episode’s plotlines, George (Jason Alexander) is avoiding his girlfriend, Allison, who is trying to break up with him. If she succeeds, he’ll be dateless for the Pinstripe Ball, a black-tie event held by his employer the New York Yankees. He plans to make a grand entrance at the gala by twirling Allison around to show off her backless evening gown; according to Costanza, that’s the way classy people do it. When his girlfriend ominously tells him, “We need to talk,” he goes into hiding, reasoning that if she can’t find him, she can’t break up with him, and if she can’t break up with him, she has to go to the ball. To that end, he’s screening all his phone calls.

The scene opens on the exterior of George’s apartment building, then we see George sitting on the couch watching TV and chowing down on a bowl of popcorn while his telephone rings. The answering machine picks up, and we (and Jerry Seinfeld, rolling his eyes on the other end of the line) hear “Theme from The Greatest American Hero” start up, with George singing, off-key, the following lyrics: “Believe it or not, George isn’t at home/Please leave a message at the beep/ I must be out or I’d pick up the phone/ Where could I be? / Believe it or not, I’m not home.”

In the middle of his conversation with Jerry, George hears another call coming in and hangs up so the machine can answer. And we hear the whole message again, while George digs around in his popcorn bowl and bobs his head to the tune. The second time around reinforces the magnificent stupidity of George’s rewritten lyrics and by extension, the original song. On the “Where could I be?” line, George cockily shrugs his shoulders and raises his eyebrows with a self-satisfied smirk; he’s obviously pleased with himself for the (dubious) cleverness of his answering machine ruse. Jason Alexander’s body language in that moment is an example of an actor so dialed into his character (and after eight seasons, viewers were dialed in too) that we can read his mind from the smallest of gestures. I don’t know how many times I’ve watched this episode, and that shrug/smirk never fails to make me laugh out loud.

As always, George sees himself as a mastermind who’s getting away with something, while all we see is a “short, stocky, slow-witted bald man” (as his sort-of-friend Elaine Benes describes him) whose plan is going to implode in the end. Which makes the use of “Believe It or Not” so comedically brilliant. Serial liar George Costanza is never to be believed about anything. On a deeper level, the reference to The Greatest American Hero neatly echoes Jerry’s obsession with Superman, and plays up the fundamental contrasts between Jerry and George. George is in Jerry’s shadow on everything: looks, intelligence, dating prowess, ambition, hair. Both of them are boy-men, unwilling or unable to fully commit to the responsibilities of adulthood. But while Jerry is discerning and aspirational enough to identify with Superman, the greatest hero of all (with even greater significance for a Jewish comic book fan like Jerry), George characteristically goes for the undemanding low bar and chooses a lame Superman knock-off’s theme song to adopt as his own.

In doing so, George Costanza—or, more accurately, episode writer David Mandel—gave “Believe It or Not” an immortality it might never have achieved otherwise. Seinfeld ended in 1998 and reruns have been playing in syndication and on streaming services ever since. There are generations of Seinfeld viewers who only know “Believe It or Not” as “George Costanza’s answering machine song,” who’ve never seen The Greatest American Hero or heard Joey Scarbury’s version. The song belongs to Seinfeld lore now, a fact reinforced by the use of Scarbury’s recording in a Tide laundry detergent commercial starring Jason Alexander that premiered during the 2022 Super Bowl. (Presumably, Scarbury and Post earned some royalties for it.)

“Believe It or Not” secured its enduring place in the popular consciousness much the same way George landed every job he ever held—by a quirk of fate, despite not being good at anything. It ended up being one of TV’s most recognized and beloved theme songs, even though it’s associated with an entirely different show than the one for which it was recorded. To each successive generation of viewers who discover Seinfeld in rerun, George Costanza will forever be The Greatest American Hero.

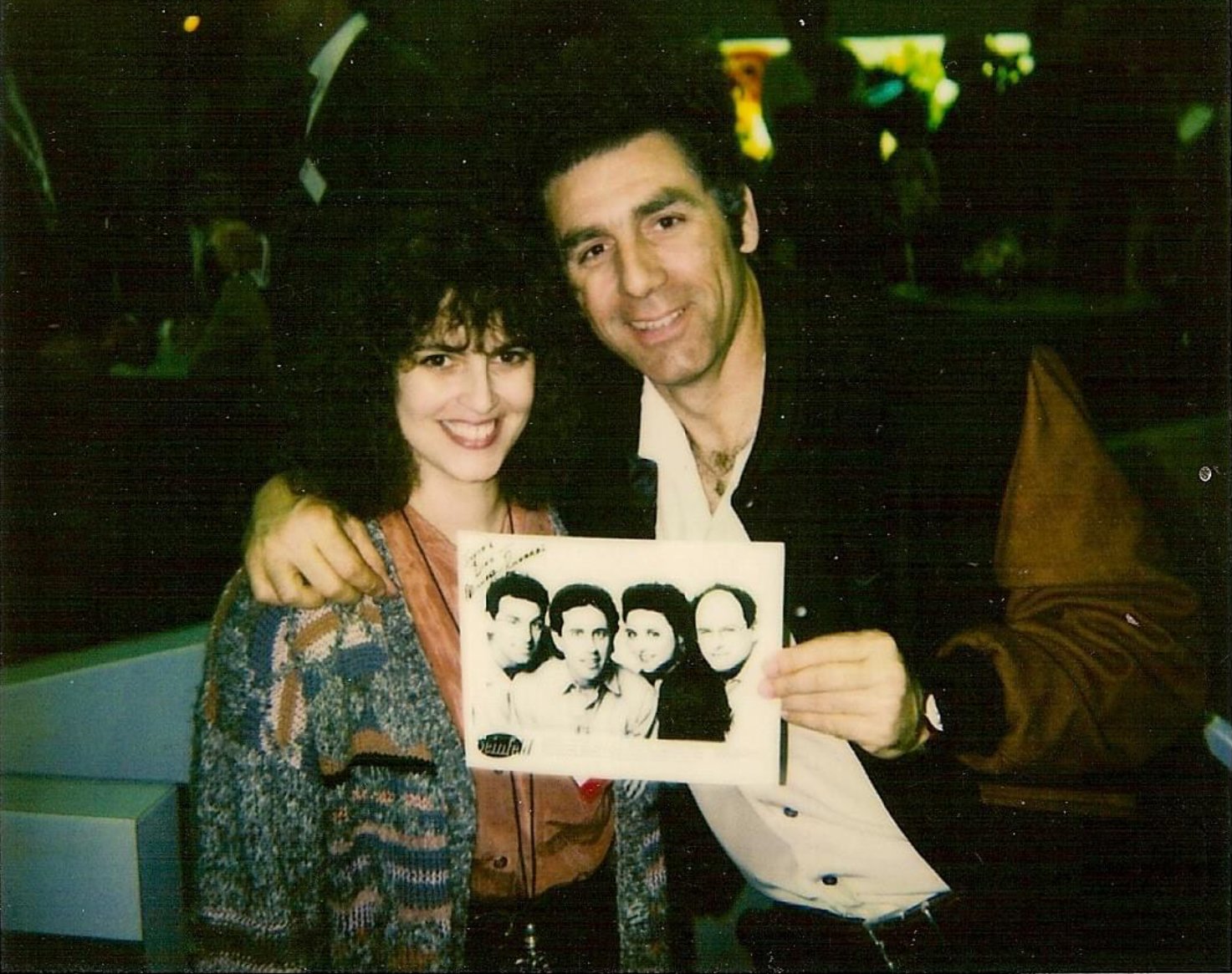

Here I am in 1993 with actor Michael Richards (Kramer on “Seinfeld”) at a TV syndicators’ convention in San Francisco. I was a TV critic for the SF Examiner at the time, but I was on a “Seinfeld” fan mission: Meet all four cast members and get their autographs. After this photo was taken, I had a lovely chat with Jason “George” Alexander, the subject of my March Fadness piece today, but the photographer had disappeared. (Mission accomplished, by the way.)

Joyce Millman started her writing career in 1981 as a music critic for the Boston Phoenix. She was the Pulitzer Prize-finalist TV critic for the San Francisco Examiner, and a founding staff member of Salon. She has also published humor essays in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Belladonna and Points in Case. She lives in Seattle with her husband, and considers watching Seinfeld before bedtime a form of self-care. Her blog and archive are at joycemillman.wordpress.com.

scott edward anderson: STUDIO LOG: the tom tom club’s “Genius of Love,” A Memoir and Exposition in 18 Tracks

ARTIST: Tom Tom Club

PRODUCER: Scott Edward Anderson

TITLE: “Genius of Love”

DATE: March 2023

TRACK 01: “My New Wave Transformation” | Deadpants and Heatwave

April 1980. My pal Doug and I make our way to NYC to check out the music scene. We arrive just prior to a major transit strike. Doug and I bonded over music through our high school Radio Club in suburban Rochester. This trip—where we also meet the street artist known as Adam Purple—is part of a musical awakening for me that started with Devo’s performance of “Satisfaction” on SNL in October 1978. (See Erin Belieu’s excellent essay on that song from last year’s MF.) Doug brought the record into school the following Monday so we could play it on the air.

We’d heard about the Mudd Club and CBGBs and decided to check it out for ourselves. Up until that time, I’d been a hippie wannabe—born on the tail end of boomerdom, my musical tastes had been shaped by my baby boomer aunt and uncle, Liz (The Beatles) and Buzzy (70s glam rock); my father’s best friend Carl Boren, who moonlighted as a DJ known as “The Ghost,” and who had the most amazing record collection I’d ever seen (he was the first to turn me on to Harry Nilsson’s “Nilsson Schmilsson,” still an all-time favorite); and my father’s 45 collection (now in my possession) consisting mostly of 50s doo-wop, Elvis, Sam Cooke, Motown, and early rock and roll. My father also passed on his love of Johnny Cash, which somewhat ironically led me to an obsession with Bob Dylan after his appearance on Cash’s primetime TV variety show. My stepmother Sandra’s collection of iconic late 60s-early 70s LPs—Neil Young, CSN, CSNY, Linda Ronstadt, Joe Cocker, and the Woodstock Soundtrack—rounded-out my musical tastes, along with my friend Lindsay who turned me into a mid-to-late 70s Deadhead. All that is about to change with this trip to NYC.

Mudd Club, CBGBs, the grit and grime of New York, the stench of the urine-soaked subway, graffiti everywhere, and all the used record shops and bookstores and vintage clothing shops. I fall in love. I cut my hair, form a punk band we call Deadpants, and enter a battle of the bands at the Monroe County Fair in the Summer of 1980. (See reference below.) We take Third Place against some country bands by performing a butchered quasi-punk-Beatles take on Buddy Holly’s “Crying Waiting Hoping” and a song called “Surf Ohio,” which I wrote (under the pseudonym “Iggy Stamp”) with our drummer, who went by the nom de drum, “The Mouse.” I am 16 years old.

A funny thing happens later that summer: we meet Jan & Dean (of “Surf City” fame) at the House of Guitars in Rochester and pitch the song to them. They are interested, but Jan struggles with drug addiction and it never happens. Here are the lyrics to “Surf Ohio”:

Some say Honolulu is the place to be,

But Cincinnati and Akron will suffice for me.

Come on and go Surf Ohio

It’s the place to be!

Come on Surf Ohio

Won’t you come along with me?

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (oh, baby!)

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (place to be)

Surf, surf, Surf Ohio,

Come on baby let’s go down,

Let’s go surfing on the ground!Some say California is the only one,

But give me Cleveland or Ol’ Dayton.

Come on and go Surf Ohio

It’s the place to be!

Come on Surf Ohio

Won’t you come along with me?

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (oh, baby!)

Surf, surf surf, Surf Ohio (place to be)

Surf, surf, Surf Ohio,

Come on baby let’s go down,

Let’s go surfing on the ground!The drinking age there may be 21,

But stomping on the beach can be a lot of fun.

Come on and go Surf Ohio

It’s the place to be!

Come on Surf Ohio

Won’t you come along with me?

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (oh, baby!)

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (place to be)

Surf, surf, Surf Ohio,

Come on baby let’s go down,

Let’s go surfing on the ground!Well, the Banzai Pipeline is for surfer fiends,

But give me a sewer on the Erie Scene.

Come on and go Surf Ohio

It’s the place to be!

Come on Surf Ohio

Won’t you come along with me?

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (oh, baby!)

Surf, surf, surf, Surf Ohio (place to be)

Surf, surf, Surf Ohio,

Come on baby let’s go down,

Let’s go surfing on the ground!(lyrics copyright 1980 Iggy Stamp and The Mouse)

That is my first missed opportunity to be a “one-hit wonder.”

Later that August, Doug and I and a group of others drive North to Canada for the Heatwave Festival at Mosport Park outside Toronto, where we see Elvis Costello, the B52s, Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Rockpile, the Rumour (without Graham Parker), and Canadian bands Teenage Head and The Kings. The Clash are supposed to be on the bill as well, but rumor has it they get detained at the border for some reason. (Someone else says later the Clash were pissed that Elvis Costello got top billing and not them.) The festival is called the “New Wave Woodstock,” we are in post-punk heaven. I move to NYC that Fall and never look back.

TRACK 02: Tom Tom Club, “One-hit Wonder or….?”

People say I’m a one-hit wonder

But what happens when I have two?—Sharon Van Etten, “Every Time the Sun Comes Up”

Tom Tom Club had two hits, actually, so I’m not sure they qualify for the category of “one-hit wonder,” unless you restrict it to the Billboard Hot 100. “Wordy Rappinghood,” their first single for Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, made it to #7 in the UK.

Tom Tom Club was a side project of Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth, the drummer and bass player of Talking Heads, and came about when David Byrne and Jerry Harrison decided to work on some solo projects after Talking Heads’ Remain in Light.

TRACK 03: “Wordy Rappinghood” | Tom Tom Club

Sometime in the summer of ’81. I walk into a club to hear someone tapping a typewriter over the PA, followed by a funky synth and steady, simple drumbeat. Then a bit of what sounds like Yoko Ono sing-saying, “What are words worth? What are words worth? Words.” Immediately followed by a monotone, Nico-influenced laconic “rap” about “Words in papers, words in books/ Words on TV, words for crooks,” then a bit of French thrown in. The rhymes are sometimes fantastic, sometimes forced. The beat is funky and synthy and fun. It’s catchy and I find myself hearing it in all the clubs, Hurrah!, Mudd Club, Danceteria, Palladium, Pyramid, and Club57. What is this? When I ask a DJ spinning the disc he tells me it’s a band called Tom Tom Club, which I later learn consists of one half of Talking Heads.

TRACK 04: “Natural Source” | Gilda Radner

Spring 1981. One of my first jobs in New York is as a baker’s assistant at Natural Source, a small upscale bakery on West 72nd St and Columbus Ave. Most of my time is spent running baked goods from the kitchen on 71st and hand-trucking tubs of ice cream from the basement to the shop on the corner.

The early 80s are a potent, gentrifying time on Columbus Avenue and the Upper West Side. New York Magazine dubs it the “New Left Bank,” pointing to Charivari’s high-end fashion store, the original Silver Palate restaurant, numerous galleries, and even a Texas bootery called “To Boot.” (I still have a pair of Noconas they threw out because of a tear in the snakeskin.)

I learn a lot about baking from the baker, a woman named Lesley who later went on to work for Sarabeth’s Kitchen. (We sold Sarabeth’s marmalade when she was still making it out of her apartment.) I also learn a valuable lesson about customer service.

Occasionally, during my runs I find the shop crowded and offer to lend a hand at the counter. The counter crew don’t like a bakery “runner” crowding in on their territory and tips, so I do it sparingly. One time, a woman dressed as a bag lady comes in. No one waits on her.

“Can I help you?”

“I’ll take the ugliest pastries you have,” says the woman.

“We don’t carry ugly pastries, lady,” the impatient counter help replies. “Why don’t you try another store.”

The woman looks annoyed. I step in and offer, “If you want ugly pastry, come back with me to the kitchen. We’ve got a bunch that will just be tossed otherwise.” Counter-help glares at me.

She follows me to 71st Street. I explain the situation to Lesley, and she gives me a paper bag full of discards. Back on the street, I hand it to the woman.

“Thanks, sonny,” she says, adding, “Do you know who I am?” She looks familiar, but I can’t place her. Frankly, she looks like every other bag lady on the Upper West Side. I shake my head. She tosses hers back and shouts, “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!”

After that, whenever the “bag lady,” Gilda Radner, comes by the shop, she asks for me (she always calls me “Sonny”) and I bring her the ugliest pastry discards I can find. I never tell anyone at the store who she is; it’s our little secret.

TRACK 05: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 1)

“Tina wrote some amazing words in tribute to our favorite soul, funk, and reggae artists, but wanted a third verse,” Chris Frantz writes in his memoir, Remain in Love: Talking Heads, Tom Tom Club, Tina. “I gave her these closing lines: ‘He’s the genius of love, he’s got a greater depth of feeling. Well, he’s the genius of love. He’s so deep!’ She loved it and declared me a genius!”

TRACK 06: “Gossamer Wing” | The Breakfast Club

Another early job of mine in NYC. I’m working for the design company Gossamer Wing in the Garment District, hand-painting silk for Mary McFadden and Anne Klein dresses, and chamois shirts for Ralph Lauren. One of the designers, Dan Gilroy, has a band called the Breakfast Club, for which a young Italian American woman from Michigan plays the drums. Madonna Ciccone tells everyone, including me, that she’ll be famous one day. Yeah, right, I think. Me too.

TRACK 07: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 2)

Tina Weymouth sings and co-wrote “Genius of Love,” but she didn’t play the bass on the recording even though she wrote the bassline. “When it was time to do that track my whole right arm seized up in a terrible cramp, and I couldn’t play,” she told Bassplayer.com. “I had never played in the studio around the clock like we were doing, so I didn’t even know that could happen. I ended up waking the assistant engineer—he was asleep under the console—and I showed him the part, and he played it. Chris was mad, but I really couldn’t play; my hand wouldn’t even close.”

TRACK 08: “Gotta Dance (Dance It Away)” | Active Driveway

Early ‘82. My own band, Active Driveway, for which I play bass and sing, this time under the pseudonym Dash Beatcomber, releases a cassette-only single called “Gotta Dance (Dance It Away),” which gets a lot of airplay on WFUV and WFMU. This is as close as I get to being a one-hit wonder. The song is a curious mashup of post-punk, Nina Hagen, and The Cramps. We never get a record deal.

Here’s our entry from the web page, “Lost Rochester Bands”—I still don’t know who wrote and posted it (https://rocwiki.org/Lost_Rochester_Bands):

Active Driveway - early 80s post-punk band that emerged from the ashes of Deadpants (“Surf Ohio”) and that bands’ triumph at the Monroe County Fair in the summer of 1980. Active Driveway featured the pseudonymous Dash Beatcomber (fretless bass, lead vocals), Dora Brilliant (vocals), Joshu (guitar), and Keith Fraemont (drums, tape effects) and had a popular post-punk song, “Gotta Dance (Dance It Away),” which was in heavy rotation on WFUV (90.7, NYC) in 1981-82. The unique vocal styling of Beatcomber and Brilliant was influenced by Nina Hagen, Lene Lovich, Yoko Ono, the Flying Lizards, and Public Image, Ltd., while Fraemont and Joshu were the musical backbone of the group. The duo brought a heavy guitar and drum sound to Active Driveway’s cover of The Who’s “My Generation” and early “sampling” experiments utilized on “Can You Teach Me to Fly Like That? (Jonathan Livingston Seagull).” While associated with the Rochester scene, the band also had tentacles in New York City and Cleveland, Ohio, including possibly opening for the Psychedelic Furs. Their exploits were frequently covered by Rockstop Magazine, which was started in part to promote this and other projects of Beatcomber’s alter-ego. Active Driveway recorded and released their music (“Active Driveway: Do Not Stop”) on the cassette-only indie label, Sorry Kitten Records. They disbanded in 1985 after recording now-lost versions of an original “Blondes On Bikes” (Beatcomber/Joshu) and a [sic] early alt-country cover of Bob Dylan’s “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.”

TRACK 09: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 3)

“For ‘Genius of Love,’ Tina played the Prophet 5 part, the dee-deet of bar one, then the dee-deet of bar two, and repeated that two-bar pattern for the whole song,” Chris Frantz writes in Remain in Love. “I then added the corresponding syncopated deet-deet that led back to the downbeat of Tina’s dee-deets of bar two. Simple, but powerful. We made a pretty good team.”

TRACK 10: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 4)

“After building a number of basic tracks, we invited Adrian Belew down to Compass Point to play some guitar,” Frantz writes in Remain in Love. “Monte [sic] Brown came to the studio again to play a lilting Bahamian-style rhythm guitar part on ‘Genius of Love.’ This sat well in the groove along with Adrian’s snaking, slithery picking part.”

TRACK 11: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 5)

“It probably took two 16-hour days to complete, but once we had the bass and drums, we already knew we had a hit,” Chris Frantz said in an interview for Songfacts. “Usually, you wouldn’t say, ‘This is a hit,’ because you don’t want to jinx it, but I think everybody in the room knew it.”

TRACK 12: “Wheels of Steel” | 434 Copy Center

Summer of ’82. I’m the manager of 434 Copy Center on 6th Avenue between 9th and 10th Streets. Actually, I’m co-manager, sharing duties with Renée, a young Black woman from BedStuy. We are an eclectic, mixed-race crew and, after closing, a bunch of us often go over to the Roxy, where Kool Lady Blue hosts her “Wheels of Steel” parties. We dance the night away to early hip-hop like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message,” “Planet Rock” by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force, and reggae-influenced New Wave like Blondie’s “Rapture” and “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” by The Police. There is one song, however, that we can’t stop grooving to: “Genius of Love” by Tom Tom Club.

The record came out in the Fall of ‘81, yet the previous summer discs imported from the UK started making the rounds. (They sell over 100,000 copies of the single as imports before getting a record contract in the States.) Soon it is everywhere, spilling out of boomboxes on the basketball courts on West 4th St., on subways, and anywhere that plays WBLS.

Later that year, the song’s captivating groove starts showing up in samples on other songs. Sampling is a new technique we’d experimented with in Active Driveway (as alluded to above) by taking a spoken-word record of Richard Harris reading from Jonathan Livingston Seagull, for our track called, “Can You Teach Me to Fly Like That?”

Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde’s “Genius Rap” is among the first to sample “Genius of Love,” along with Grandmaster Flash’s “It’s Nasty.”

“Genius of Love” is still, after four decades, one of the most sampled records, including songs by such artists as Mariah Carey, the X-Ecutioners, Snoop Dog, Busta Rhymes, 50 Cent, Ice Cube, 2Pac and the Outlawz, Warren G, and even, most recently, Latto with “Big Energy.” Ziggy Marley also used it—with the help of Weymouth and Frantz, who produced the record, a remix of “Tumblin’ Down,” for his Conscious Party album.

TRACK 13: Origin of “Genius of Love” (Take 6)

The funky groove of “Genius of Love” owes a lot to Zapp’s “More Bounce to the Ounce,” which came out the year before, and is matched by the cute white-girl rapping of Tina Weymouth and her sisters, paying tribute to Black singers and musicians like Bootsy Collins and George Clinton of P-Funk, Smokey Robinson, Bob Marley, Sly and Robbie, Kurtis Blow (“who needs to think when your feet just go?”), and disco drummer Hamilton Bohannon (himself a one-hit wonder with his 1975 single, “Foot-Stompin’ Music,” which hit the Billboard Hot 100), and, of course, James Brown. The lyrics were as catchy as the riff.

“It’s beyond an earworm,” as Chris Frantz told Vanity Fair. “We got lucky.”

TRACK 14: Rockstop! Magazine and MTV | Dash Beatcomber

Fall 1982. I launch a magazine (really, a ‘zine) called Rockstop! (which I maintain you can interpret two ways: “Rock’s Top” or “Stop Rock,” take your pick) mostly to promote Active Driveway (see reference above). We take the name Active Driveway because there is free advertising on garage doors all over New York City—we don’t stop to consider that no one will realize it’s advertising for a band.

The shop owners at 434 let me print copies of the magazine in our off hours, which we distribute free in the same record shops, used bookstores, and vintage clothing shops I’d discovered on that trip two years earlier. I even enlist my UK friend, Shabir, who we’d picked up hitchhiking to Canada on our way to the Heatwave Festival back in 1980 (he got stopped at the border because his passport was stolen in Texas), to write about the British music scene, turning our readers onto what was happening across the Pond.

Creativity is in the air, despite it being the Reagan Years or perhaps because it is the Reagan Years, and the threat of the Cold War and Nuclear annihilation still looms. What else do we have? One of the regular customers at 434 is the design team that creates the logo for MTV, which has just launched. I get chummy with one of the designers and they ask me to appear in a commercial they are shooting for MTV-branded merchandise. Somewhere in a vault (I hope not!) is a video of me sporting a red hoodie with a yellow MTV logo, acting as a sports team coach complete with a clipboard and a whistle. (Years later, I become that coach when I take the helm of my kids’ Little League teams.)

TRACK 15: “Genius of Love” on the charts

#1 Billboard Disco Top 80

#2 Hot Soul Singles Chart

#31 Billboard Hot 100

TRACK 16: Four stand-out performances of “Genius of Love” worth checking out on YouTube:

The original music video for the song (apparently one of the few music videos Frank Zappa liked), featuring original drawings by Jimmy Rizzi.

Jeffrey “Twirlee Dee Lite” Dollison spinning and juggling a basketball to “Genius of Love” on Soul Train.

Tom Tom Club’s appearance in the film Stop Making Sense. They performed on that tour during a costume change for David Byrne to put on his famous “big suit.”

The group’s Tiny Desk concert acoustic version for NPR, which also includes “Wordy Rappinghood” and “Only The Strong Survive.”

TRACK 17: “Who Feelin’ It” | Tom Tom Club

1999: Tom Tom Club release a kind of sequel to “Genius of Love,” called “Who Feelin’ It,” updating their list of influences to include the Beastie Boys, Grandmaster Flash, the Fugees, Al Green, Otis Redding, Marvin Gaye, Fela Kuti, Afrika Bambaataa, Manu D’Bango, Bernie Worrell, and Lee “Scratch” Perry, who they wanted to produce the original “Genius of Love,” but their signals got crossed and it never happened.

TRACK 18: “While the Cat’s Away” | The Brothers from the Same Motha

Late 1986. I quit music and move to Germany and Paris. While I’m away, one of my brothers sells my guitars, basses, and amps; another brother steals a large part of my record collection, which he still has, although he denies it. They think I’m never coming back? Tom Tom Club is one LP not pilfered. “Genius of Love” is Track 02.

The author as "Dash Beatcomber," circa 1982, with one of Active Driveway's free advertisements.

Scott Edward Anderson is an award-winning poet, memoirist, essayist, and translator. He is the author of Wine-Dark Sea: New & Selected Poems & Translations (2022), Azorean Suite/Suite Açoriana (2020), the Nautilus Award-winning Dwelling: an ecopoem (2018), and two books of nonfiction, including Falling Up: A Memoir of Second Chances (2019) and Walks in Nature’s Empire (1995). Find him @greenskeptic