round 1

(7) the pixies, “wave of mutilation (uk surf)”

wiped out

(10) tool, “sober”

318-151

and will play on in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 7.

a mutilated life or really good fiction: stephanie mankins on ”wave of mutilation (uk surf)”

It starts with a kick. A wet kick, drenched in reverb. Then the snap of a snare.

BOOM-BOOM-CRACK. BOOM-BOOM-CRACK.

BOOM-BOOM-CRACK. BOOM-BOOM-CRACK.

The bass sends in a string of single notes so low

DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA,

That we’re surprised when the next ones are even lower.

DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH.

We’re pulled down, wading through ten million pounds of sludge from New York and New Jersey. It’s a soft sludge, comforting, and we sink back into it like an old, familiar chair and ride it through to the end of this long, long day.

The strumming of an acoustic guitar fades in. It’s a ramp that launches us into the full song made complete by a haunting melody picked out on an electric. We’re awash in tremolo, wavering in time with the beat. We’re being prepared by magicians to receive the enigmatic lyrics of this fucked-up lullaby, sung in a breathy voice:Cease to resist, given my goodbye

Drive my car into the ocean

You think I’m dead, but I sail away

On a wave of mutilation, a wave of mutilation

I was home from college on winter break the first time I heard the Pixies. There were seven or eight of us standing around my parents’ dingy suburban living room drinking Milwaukee’s Best—a truly unspectacular swap meet of bad roommate stories and new music finds—when someone asked if I’d heard the album Doolittle. I shook my head; I hadn’t even heard of the band. Jewel cases were shuffled, a cd was lifted from the flimsy plastic tray and another set in its place.

For someone else, someone much older, maybe, it might have been merely a young band’s sophomore effort, but for those of us straddling adolescence and adulthood, it was a seismic shift. Suddenly, our lives were as extraordinary as we’d dared hope they were, our moment in history as seminal as we’d always felt it could be. No longer were we me and you, sneaking cigarettes in your beater, moving pieces around a chess board we’d never master, earning minimum wage at Corn Dog 7 in the mall north of Dallas. We were gigantic.

The album’s third track, Wave of Mutilation, moves quickly with an intensity typical of many Pixies songs, but as the languid UK surf version proves, its power isn’t tied to tempo. If anything, the slower pace allows us to dive deep into the broodingly surreal and morbid existentialism that is the first verse. According to Black Francis, these four lines are about the 1980s phenomenon whereby foundering Japanese businessmen would commit murder-suicide—driving themselves and their families off a dock and into the ocean. Pretty gruesome stuff, yes, but I wonder—does it matter if you know what the lyrics mean, or where they come from?

Fast forward thirty years: what matters to me now isn’t exactly what mattered to me then, music or otherwise, which is something I attribute directly to becoming a mother. Having kids doesn’t diminish the importance of music, but it definitely rearranges priorities. Or maybe music is merely easier to lose sight of when faced with the more pressing demands of small humans: warm food, snacks, clean clothes, snacks, or replying to the urgent email from the school nurse who’s threatened to bar my daughter from virtual school unless I send in her immunization records immediately. Did I mention snacks?

Before I had children, music was all about me and my experience. Not that I didn’t marvel at its beauty and power, but I was always searching for what I could take from it. What could it do for my own music? How could knowledge of this or that aspect of this or that band elevate my standing among peers? What knocks me over now is realizing that there are whole musical worlds my kids don’t know about. There’s so much I sometimes feel like I can’t play it fast enough—songs and albums and bands that shaped my life—and the best part is that it has nothing to do with me. At least, I’m not looking to gain anything from it, not in the same way. I love to see their reactions, how one band will thrill them while others don’t seem to make an impression at all. Or it’s even simpler, a single moment: I can call out, Cease to resist, and one, if not both of them will answer back, given my goodbye. Depending on the mood, we may sing the next line, and the next, or even the whole verse, ending on wave of mutilation, something not one of us can easily define.

I hadn’t really given that phrase too much thought before I started this essay. I didn’t need to. The song’s fragmented, evocative imagery coupled with its singular sound was powerful enough to capture the raw angst of my late-teenage years, a vulnerable age when music tends to bore its way into your DNA. After that, the song and everything it encompassed were mine, and not something I needed to continue questioning. The same way I don’t think to ask why the sight of a slow-building thunderstorm—all blacks and blues and grays in constant collision—hovering above acres of tall, skinny pine trees comforts me. The same way I don’t wonder why sweet iced tea and salty fried okra always and forever belong to summers in east Texas.

Even so, wave of mutilation? What the hell is that?

My sister says that human existence can be thought of like waves in the ocean—each life one wave; each life a brief expression of a timeless entity too vast to comprehend. We are, every one of us, made up of the same stuff as everyone else. I like this analogy. It wouldn’t have meant much to me thirty years ago, but now it’s reassuring. My individual worries, the problems that threaten to overwhelm my day-to-day, are not unique to me. I am not alone.

The next step is a simple mathematical equivalency: If a wave is a life, then a wave of mutilation is a life of mutilation—or, a mutilated life. We all have our wounds, some of us more than others. Some of these wounds fade with time, but others leave us permanently scarred. If the scars are small or well-placed, we cover them up and get on with it. But if there are too many to hide, or they’re too large to disguise? What does it take—how many cuts—to render an entire life irreparable, mutilated beyond recognition? How damaged does your life have to become for you to no longer want it?

A few weeks into my first semester of graduate school, I arrived to my “Craft of the Essay” class and was met with the news of David Foster Wallace’s suicide. The mood was somber and many were shocked, though if you’d read even a little of his work, you couldn’t have been too surprised. Depression, suicide, and the agonizing mundanity of life figure prominently in all of his fiction. The conversation continued around the table as more students arrived, the word ‘tragedy’ thrown about as if it were a given, indisputable. While it’s almost always true that a suicide is a tragedy, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes it’s the life that’s tragic, and the suicide is the only response, the only way out.

I can’t say I was saddened by his choice, not exactly. I was sorry that his life was so painful he decided it wasn’t worth living, but there’s a difference. I couldn’t articulate this difference immediately and it took some time to process, but in the end, I was relieved. I felt relief for him. His family and friends were grieving the loss of him personally, that I understood. The literary community at large, on the other hand was grieving the loss of what could have been—assuming that had he lived, he would have continued to create phenomenal art—but I couldn’t. Not then. It seemed selfish to even contemplate whether someone’s suffering was worth what that suffering could produce.

And it was his suffering that produced his fiction. He and his characters may have inhabited different worlds, one real and one not, but they were equally dark. Wallace once said, as if speaking directly to this connection, “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.” Popular music—rock, grunge, whatever—may not be fiction per se, but it is a fiction, and the best of it, like Wallace says, is about what it means to be human. Or, as in the case of :”Wave of Mutilation,” maybe what it means to fail, to give up being human.

There’s more to being human than suffering and failure, though: enter Wallace’s definition of really good fiction. In an interview with Larry McCaffery, an English professor at San Diego State, he said, “Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished, but it’d find a way both to depict this world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it.”

Can we see these possibilities in “Wave of Mutilation?” I was discussing this with my fourteen-year-old daughter the other day, and when I told her how Francis came up with the first verse, her gut reaction was horror followed by a resounding No! But the character in the song is not necessarily the same as the real-life businessman who killed his family and himself. Given the second line, You think I’m dead, but I sail away, you could be forgiven for deciding our character doesn’t die, that to sail away on a wave of mutilation is to accept that life is suffering and then continue to live, even if it’s a mutilated life, even if that mutilation is self-inflicted.

The second verse, and the song’s only other lyrics, is equally ambiguous.

I've kissed mermaids, rode the El Niño

Walked the sand with the crustaceans

Could find my way to Mariana

On a wave of mutilation

Sure, the world of kissing mermaids and riding a climactic condition (El Niño) is fantastical, but no one said realism is the only kind of fiction that can be great. Children live in fantasy worlds, and maybe that’s the best way to deal with a crappy reality. Plus, Mariana could be a woman, and love is always hopeful. That is, until you learn that Mariana is a reference to the Mariana Trench, the deepest oceanic trench on the planet. It’s hard to argue that finding your way there could mean anything other than dying and sinking to the bottom of the sea. Then again, the character says he could find his way to the Mariana trench, not that he necessarily did.

Lucky for us, in trying to decide if the song meets Wallace’s criterion for really good fiction, we’re not restricted to the lyrics alone. Unlike fiction that exists solely on the page, the fictional worlds of songs are created by music as well, and in the Pixies case, nothing is more alive than their music. It’s alive not only because it makes you feel alive when you listen to it, or because it serves as a bridge to your former lives, but also because it’s widely acknowledged to be the starting point for the era of 90s guitar rock, influencing such bands as Radiohead, PJ Harvey, Weezer, Soundgarden, and Nirvana.

Whether Wallace’s fiction succeeds in depicting a world that is both dark and includes possibilities for being alive and human, I can’t say. In the very least, it’s beyond the scope of this short essay. But if you’ve found this to be true in his work, you’ve found it, and it’s yours. Be thankful. I’m only sorry Wallace himself never did.

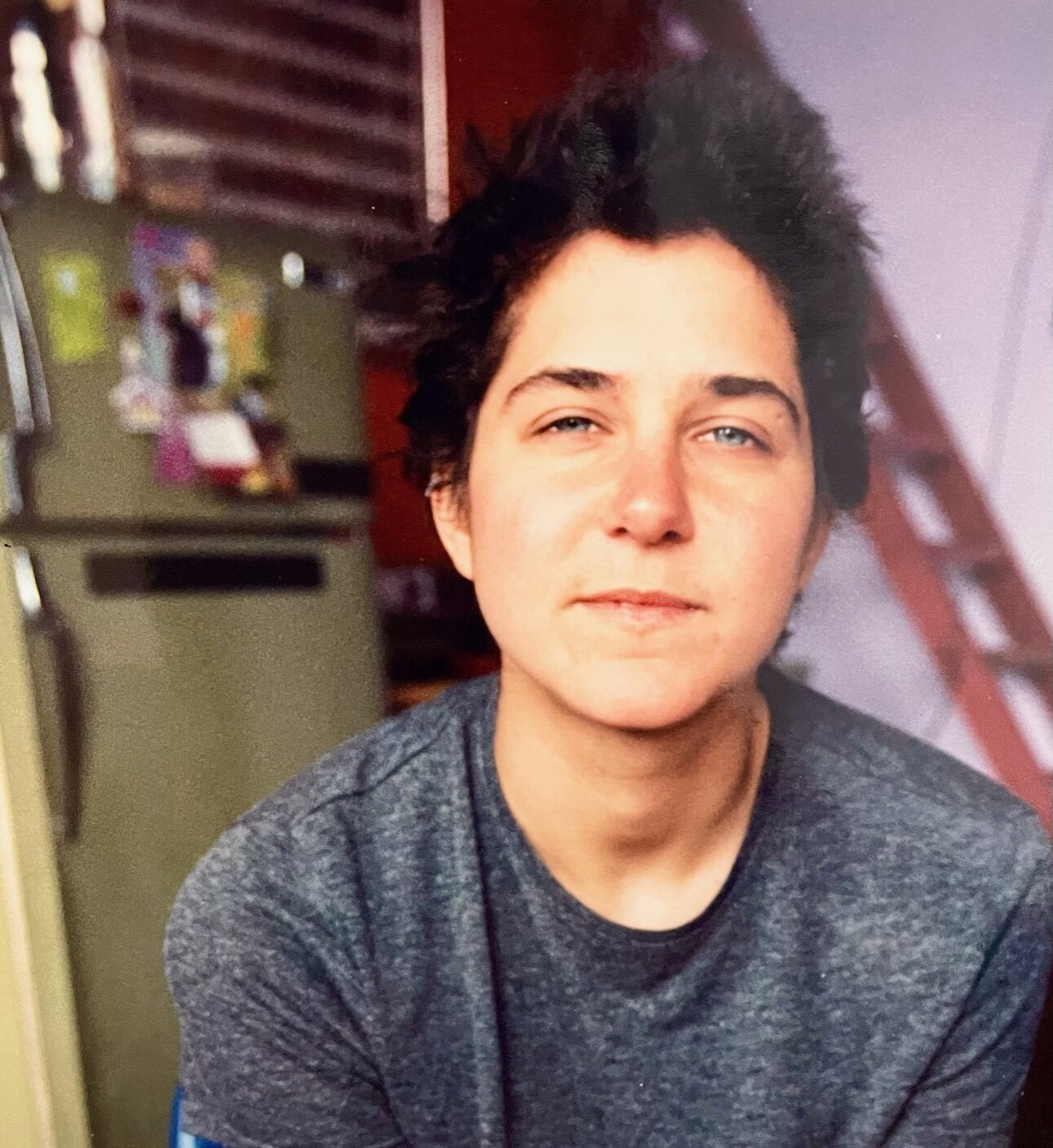

Stephanie Mankins graduated from Brown University with a B.A. in mathematics, and from Sarah Lawrence College with an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction. From 1998-2004, she and her band, Adult Rodeo, based in Austin, TX, recorded and released four full-length albums: The Kissyface (1999, Shimmy Disc); Texxxas (2000, Shimmy Disc); Long-Range, Rapid-Fire (Four States Fair, 2001); and Tough Titty (2004, Four States Fair). In 2016, she finished a short documentary about her sister’s decision to get a cochlear implant, Do You Hear What I Hear?, which can be found here: https://vimeo.com/167353167 She lives in Brooklyn, NY, with her husband, two kids, and their dog, Iggy. She’s currently working on her first novel.

What color is the pain in your soul: rebecca chapman on “SOBER”

To be honest, I don’t really remember my head hitting the vinyl-covered concrete of our foyer. It was 1984, and my dad had thrown me down the stairs for the third time that night. By itself, that was not an unusual event. I usually did something to piss him off. Not that I could have told you what exactly triggered the outbreak. But this time, I felt frozen. I could not move. I could not breathe. I had a strange, detached feeling about the matter. I cataloged the feelings, or lack of feeling, and wondered if this was the night that I would finally die. It was not my first time with these thoughts, and it would not be the last time that I would wonder.

But what made this night strange was my mother. He was shouting at me to get up, but I could not move. I could not respond even if I wanted to. The seconds felt like minutes, but they were probably only heartbeats. That was long enough for my mother. She flew down the stairs, past my dad, who also seemed frozen, and came to my side. She started sobbing and telling him that he could have killed me. Maybe I even had a concussion. My mother’s tears made it seem more real. My mother’s tears finally made me afraid.

My sister flew down the stairs at that point. She screamed at dad and told him to go away and not touch anyone. That’s when he appeared to thaw and move back a step. Was it surprise on his face? I never asked him, but then again, I do not think he would have remembered. My mother’s sobs mixed with my sister’s righteous anger and washed over me. I could finally take in a small breath, and make a sound like, “ughhh.” Not the most profound statement. But it was enough to watch the relief flow across my mother’s and sister’s faces. Was it there on dad’s face too? I was never sure if I caught that.

I had the wind knocked out of me. Nothing more. Okay, there were also a multitude of bruises and welts, but nothing that would cause permanent, physical damage. But the memory of that night stayed with me. The memory of how my father’s blind rage affected everyone around him. That night blended with so many others in my mind, and gave me fuel for years to come.

I grew up quiet. That was an important survival tool in my house. You had to be quiet, studious. If you could manage the superpower of invisibility, then even better. Being quiet meant fewer times that you could be noticed. Fewer beatings. Fewer times that my mother would cry and my older siblings felt they had to turn into human shields to protect me.

But being quiet did not mean that your feelings were quiet. I know my feelings could never remain quiet. No matter how hard I tried to quiet my inner life, I still felt things. I could imagine the feelings inside as a swirl of color and light, or color and shadow. It stayed with me, the maelstrom, until I could give each one a name, an image, a shape, and gain some understanding over it.

It was music that first gave me the ability to name each feeling, give it shape and definition. The music gave the feelings a voice. Sounds melding together to create images and pictures. I no longer felt locked inside my own cage. I could understand the feelings. I could find the words to express them outward. I could control the feelings so that I used my words and thoughts as my mode of expression. Many bands have provided the background music for my emancipation of the mind and soul. That said, TOOL and their music gave me some of the most expressive moments of emancipation.

Beyond my own experience, TOOL is a successful band with a large following. To date, TOOL put out five studio albums, plus a box set and one EP. As a band, TOOL defies easy description. They have been called alternative-metal, rock, art rock, post-metal, or even progressive-rock. Their combination of visual art with long, complex musical structures marks them as a band with much to delight, confound, and surprise the observer. Attempting to describe them, or the music, in a short, bumper-sticker statement, is surely a wasted endeavor. While any description is sure to fall short, I will attempt to describe one song from my own point of view, using brief description to convey the feeling and art.

In describing “Sober", I find myself considering imagery of metaphysical light and dark. The voice of an angel that has already fallen. The chords of guitars weaving silken threads of rage and midnight. The alchemical timekeeping of drums that weave a protective shell. The music wraps your body in a cocoon. The waves washing over you, enveloping you, encasing you within its layers. Lulled and soothed by the fallen angel, you emerge from the cocoon fully transformed. Never again to be the same, you are filled with a sense of understanding. The darkness in the music looked into you, and your darkness looked right back and recognized it. This is the heart of the metamorphosis. These are the transformative properties of a song like “Sober” from TOOL.

I was sixteen at the time when I first listened to “Sober".” My parents had divorced, and my mother, like many at the time, worked three jobs to make the bills. That turned me into a latch-key kid that got myself home, fed, and completed all homework and chores before anyone else came home.

That day, I had returned home from school and turned on MTV. They actually showed videos back then. “Sober” came on. It is a stop-motion animation inspired by the art of Adam Jones, the guitarist of TOOL. The lyrics present an artist that cannot create without being under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and the fallout of that predicament. I sat transfixed, not sure what I was seeing but certain that it felt new, creative, and abstract. So much could be left to interpretation. The song itself, however, left no questions about its feelings. Frustration, rage, and despair at the loss of dreams and hopes. The feeling of being trapped in the shell of your body, the bones and skin becoming a cage. Feeling like your heart and mind are at war, unable to find peace or even a stalemate to end the cycle of destruction.

It felt like the song spoke to my own frustrations, my rage and despair. My own feelings of being in a cage of my own flesh, unable to reconcile an inward battle of feelings and wanting to be free. Uncertain of who I was becoming, uncertain of what path to take, uncertain of every decision, and a constant refrain of despair and rage at how nothing seemed to make sense in life. The storms of thought and emotion in me felt seen and acknowledged. The darkness in the song seemed to recognize the darkness in me, and vice versa. It gave me words to express it all without resorting to destructive action. That acknowledgement came at a critical time, though my sense of the music is not one shared by all.

Not every fan has a story like mine or an emotional response to the music. My friend Adam, an employee of Apple Beats, is an audiophile that loves sounds and music. Also a fan of TOOL, he notes that the sound created by the band is excellent. He looks at the musicianship of the members, and he praises their technical work over any connection to the lyrics. “The drumming and rhythmic structure is amazing,” he told me. When reviewing the music, he pointed out the precision involved in their work and how each note and song feels “propulsive” in its drive toward a greater, complex structure of sound.

But my friend did not connect to the lyrics of the music in the same way that I do. In fact, he noted that much of the themes appear disturbing and did not speak to him or any experience. That said, he was still a fan of the work based on its technical merit and complexity.

Professional critical reviews of the band and “Sober” note that the work is cerebral and thought-provoking, while maintaining a visceral, brutal hold on the listener. Their use of complex and shifting time signatures songs sets them apart from most rock artists.

Critics, mostly reviews published by non-professional critical reviewers, have accused fans of being precious and pretentious in their tastes. I’m sure they would say the same of any appreciation I’ve presented in this post. They point to the fact that Maynard James Keenan has occasionally poked fun at the music and fans. They take these fleeting, brief encounters to mean that TOOL’s music is not actually deep or thought-provoking, and all fans are simply being duped into a marketing ploy. They insist that anyone taking meaning from the work is simply engaging in a narcissistic passion play, not realizing the hypocrisy of their own delight in clever bashing.

To these critics, I remind them that TOOL fans understand that music is art, and good art is something that means different things to anyone that engages with it. If you want the music to be deep, it can be. If you see something sardonic and humorous, then you can see where the songs often provide an occasional wink and a nod. If you connect with the lyrics on a personal level, then embrace that part of the art and appreciate it. If you connect with the technical complexity of the musical structure and appreciate its craftsmanship, then celebrate that part of the art. All of these interpretations are correct from any given point of view. The problem with interpretations does not come from presenting one, but the problem arises when we insist that only ONE interpretation is correct. Insisting that there is only one way to see the music, and that all others are wrong and must be rejected, is the pretension. Most fans of the art, and particularly “Sober,” do not subscribe to that view. Nor do I.

I can only provide my own experience. My own transformation and liberation through music. Whether you notice the technical complexity and mastery of the music, or whether you notice the feelings that the music stokes within in, TOOL’s work is something to appreciate. “Sober” presented something new in music and art. It spoke to me, and to others, in a way that gave us new experiences. That is something that sets apart truly good music and art.

Rebecca Chapman is a law librarian in New York. Previously, she spent 18 years practicing Indian law throughout the country. She lives in Buffalo with her husband, a computer programmer, and her daughter. When not listening to music, she is baking, hiking, reading, researching, or watching her daughter practice tae kwon do.