(16) Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock, “it takes two”

held off

(5) Soft Cell, “tainted love”

490-391

and will play in the championship 3/31

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/30/23.

BUHM BUHM: IRENE COOPER ON “TAINTED LOVE”

The primary image is disembodied: me seeing me in the backseat of a rust-ruffled Ford Country Squire station wagon, aurally bathed in the subject of this essay. And isn’t that always at issue, this idea of being in or out of the body, or of realizing the Schrodinger state of being both in and out of the body until some practical, clinical asshole says different.

I am sixteen, July 17, 1982, and soon to be headed to Rio de Janeiro as a Rotary exchange student, when the synthpop single peaks at #8. It is entirely lost on me, though not for long, that I am to be released from the paranoid Catholic lockbox of my childhood into the technicolor (albeit still Catholic) extravaganza that (to my virgin eyes) is coastal Brasil.

I am not, at this point, a virgin by choice. In 1982, presumably straight Catholic boys in Queens are less tempted to sin than one might presume.

Gloria Jones records the original version of “Tainted Love” and releases it as a B side in 1965, the year of my birth. Jones re-records it in 1976, and includes it on the album Vixen, produced by her lover, glam rock icon Marc Bolan, of T. Rex. In choosing to cover the single, Soft Cell duo Marc Almond and David Ball cite Bolan, as well as the rough and ready UK Northern soul club scene—manifested in clubs such as Va in Bolton and Wigan Casino, which spin Black American soul music out of Chicago and Detroit almost exclusively—as major musical and aesthetic influences.

Soul. Glam. Industrial. Conceptual. Wowza.

And then there’s the video. WTF.

July 17, 1982, is seven months and six days away from Fat Tuesday, or Mardi Gras, the final day of Carnival, the celebration that precedes Lent, the Catholic period of deprivation before Easter. Growing up in a predominantly Irish enclave in Queens, I understand the sere implications of Ash Wednesday. The absence of meat on Fridays, the giving up of one’s pleasures—be that chocolate or bread or alcohol or, secretly, masturbation—is an imitative martyrdom endemic to what I understand as faith, and subsequent redemption. Sacrifice is holy; just say no. Nothing comes before Lent, and Lent is always coming.

Plucked from the muffled greyscale grit of a Jacob Riis photograph, I would drop, that next February, into the psychedelia of a Pablo Amaringo painting, 3D and fully animated, sound up. During Carnaval do Brasil, parades of samba school dancers, strategically feathered and blindingly bedazzled, lead a six-day party in an ecstatic orgy of indulgence that almost requires the restorative promise of forty days of sobriety. It’s a suspension of reality, a free pass on no-holds-barred dancing, drinking, and sex that ceases, cleanly, according to doctrine, on the threshold of the most somber liturgical observance in Catholicism.

A week or so before Carnaval, I am travelling in the north, in the Amazonian city of Manaus, staying with friends of my Carioca (Rio de Janeiro-based) host family. I am seventeen and still, reluctantly, a virgin. The couple who has welcomed me into their home are in their twenties (perhaps the man is thirty), and new parents. The woman is preternaturally gorgeous, if visibly tired. The man smiles at me a lot, says, repeatedly, I should stay in the north for Carnaval.

The woman takes me aside at some point to warn me about lança-perfume. My Portuguese is not yet fluent, but I manage to get the gist of it: lança-perfume (akin to poppers) is a mix of ethyl chloride and scent, emitted from a pressurized canister and inhaled for a quick and short-lived rush. During Carnaval, it is not uncommon, the lovely woman tells me, for someone to sneak up on an unsuspecting (non-consensual) other party with a blast of lança-perfume. Along with the high, I learn many years later, ethyl chloride ingestion can result in arrythmia, diminished motor coordination, dizziness, drowsiness, slurring of speech, loss of feeling in the legs, and hallucination. I have yet, at seventeen, to hear the phrase, rape drug. It’s all in good fun, the madonna says. There’s a song about it. But I am made aware: giving oneself up to the moment is not necessarily an act of generosity; it can, instead, look and feel a lot like sacrifice. The lamb does not consent.

In the video of Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love,” Marc Almond’s disembodied head leers over the cosmic boredom of a young man tormented with sleeplessness, subjected to the intrusion of fiery blue balls of light and the cage-dancing antics of two mudflap girl starlight demons more interested in each other than in him (though he is clearly, also, disinterested). Almond is Puck, is Mephistopheles, is a Pee Wee Herman’s evil cousin of a second-tier god, toying with the virgin, whose dream and subsequent awakening lie somewhere outside his closet of an apartment.

My own sexual awakening, unbeknownst to me, is concurrent with the emergence of what would be an epidemic of HIV and AIDS. I live in Houston after returning stateside from Rio. House of Pies in Montrose is more tenderly known as House of Guys. I work at a Stack ‘n Stash with Milton Doolittle. We sell fashionable doodads to organize one’s various closets. Still relatively recently deflowered, my worst case scenario involves herpes, maybe chlamydia, the odd crab. Milton, barely forty, eschews the clubs that yet pulse and throb with young men, is perpetually trying to quit smoking, and has a penchant for eating cold casseroles over the sink, despite intestinal troubles. He asks me to go with him to visit a friend in the hospital. Milton is afraid of hospitals. We bring a king-sized bag of M&Ms. A man who might have been young lies in a bed behind a curtain at the end of the ward. He is skeletal, and lesioned, and somehow funny, in his whisperings.

AIDS is wildfire and information is repressed, as it will be for years to come. There is medical infighting and a proprietary tussle between western nations over research of a disease that is not being mitigated, let alone championed.

In July 1982, Terry Higgins dies, the first acknowledged British casualty of AIDS. In 1982, AIDS is still widely held to be a Gay disease, a reckoning for a tainted love contained to a so-called deviant population.

In September 1982, the Tylenol Murders terrorize Chicago. In December 1982, surgeons perform the first heart transplant into a human, who lives 112 days. Also in December, Time’s “Man of the Year” is not a man, but a computer. By 1982, everything is or will be tainted: the water, the air, and of course, love. We know a kid one block over who jumps to his death, full of yearning and poisoned hope. Occasionally, a leaking body is found in the trunk of an abandoned car in the Kmart parking lot, across from the tennis courts. A ninth grade girl goes into labor in the stairwell of the E wing of the junior high school. Purity, in respect to that which is untainted and untouched, is not a thing, and certainly not a thing to be confused with innocence, a state of being wholly separate from inexperience. Innocence, in our case, does not preclude knowledge, but absorbs it, transcends it. Aspirationally, to be innocent is not to be unbroken, but to live joyously in defiance of the caustic drippings of those legacies that would make broken our only signifier.

New Zealander singer-songwriter Lorde’s 2021 cover image for her album Solar Power celebrates this kind of freedom with the depiction, photographed from below, of her very own taint, a slang term for the part of the body defined as the area of sensitive skin between the genitals (scrotum or vagina) and the anus; the perineum. Taint this, taint that. Tis, though.

For release in China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia, the image of Lorde’s taint is obscured by a sunburst. Sunlight is, for all purposes, shining right out her ass. “[H]oly light,” one Weibo user in China suggested. And indeed, the image recalls the prominent print of a crucifix emitting heavenly light that hung in my grandmother’s boarding house.

Taint obscured or in full view, Lorde’s cover reads unavoidably wholesome. Is this a generational shift, this sun-kissed embrace of oneself? But then I remember all the beautiful men and women on Ipanema beach, back in 1982, a slip of lycra to keep the sand out of the bits, bodies burnished and glowing and turning to and loved by the sun; me in my second-hand maillot, prim as a pre-Vatican II habit, shame-splotched patches of exposed Irish-Scottish flesh blistering at the suggestion of freedom and vitamin D. Love and light (as in sunlight—not neon, not dashboard, not the cloaked glow of a streetlamp) was not how I experienced, or how I believed I could experience, love. I thought (I may yet think): One must be seeded and grow in the sun to be of the sun.

Voiced by Almond, Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love” is an exaggerated wink at the indulgences and excesses of the moment, a pleather-chapped nose-thumbing to the would-be utopians of the previous decade. You can smell the cocaine, it’s been said. Jones’ earlier, arguably more soulful rendition is plaintive. She’s got to—buhm-buhm—get away. In Soft Cell’s video, while the young man does indeed flee the teasing of the two curvaceous star-figures, it feels less like an escape and more like a rejection of a heteronormative fantasy.

In the 1980s, Pee Wee Herman, aka, Paul Reubens, animates Pee Wee’s Playhouse. A childlike jester, Pee Wee embodies both innocence and bedevilment. Never sinister, Pee Wee yet emits a whiff of grown-up naughtiness, an awareness that is both costumed in and elucidated through heavily made-up character. Truth and complexity otherwise inexpressible can sometimes breathe through the veil of entertainment, the arena within which such dichotomies of innocence and knowing are allowed. But only within. Without the suit and the bowtie and the makeup, there’s just Paul Reubens, getting arrested in Florida for lewd conduct—reportedly masturbating in a pornographic theater, which was presumably pretty dark and likely hosting other people engaged in similar behavior. Gay, as Black, is an acceptable anomaly in entertainment: a costume, a stage persona, acceptable—celebrated—as long as it remains contained to the arena. Self-love: Tainted love.

Unless the situation calls for a pariah. Should anyone be tempted to confuse the popularity of the resurrected Queer Eye as evidence of widespread social progressiveness, the father of the man who shoots up the LGBTQ club in Colorado Springs in 2022 provides a reality check when he tells the press that he thanks his god his son wasn’t in the club to dance, that he wasn’t infected with the gay. Whew.

Other covers of “Tainted Love” include recordings by Marilyn Manson (2001) and by Spanish cover band Broken Peach (2021). The latter, especially recorded for Halloween, features three zombie insane asylum patients playing guitar, bass, and drums, along with three zombie nurses performing vocals. The undead: Tainted love.

Broken Peach’s version mixes in riffs from Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams” and what one YouTube commenter identified as the intro from German hard rock’s Rammstein’s Deutschland. Controversy exists over whether Rammstein’s philosophy is, as the band maintains, left wing; or if it promotes, as some critics insist, a right wing national agenda, the very agenda that manifested the Holocaust. Nationalism, as Fundamentalism: Tainted love.

In an interview with fellow Soft Cell member Dave Ball, Marc Almond talks about their efforts at the onset of the endeavor to turn their art school, multi-media aspirations into something commercially attractive. Almond uses the term, Industrial Cabaret. Ball suggests they were after an amalgam of Northern soul + Kraftwerk; Almond chimes in that maybe they were more like Kraftwerk meets Judy Garland—Kraftwerk being the iconic pioneers of electronic pop.

The original members of Kraftwerk (trans., power plant), Florian Schneider and Ralf Hütter, cite influences from German Expressionism including film directors Fritz Lang (Metropolis), and F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu), as well as architects of future-focused and unsentimental movements such as New Objectivism and Bauhaus. The period after World War I and before World War II was, for Germany, a highly creative and artistically dynamic moment, and not a naïve one. No one didn’t know trouble lay ahead. But some artists and thinkers tried to stem it.

Of Kraftwerk’s ambitions later in the century, Simon Reynolds of NPR Music writes, “Kraftwerk were inventing the '80s…Crucially, it was music stripped of individualized inflection and personality, no hint of a solo or even a flourish. ‘We go beyond all this individual feel…We are more like vehicles, a part of our mensch machine, our man-machine.’”

Reynolds talks about riding in a car on the actual Autobahn between the Black Forest and Cologne, listening to Kraftwerk’s music: “It might have been…‘Autobahn’ itself—I had to [BUHM-BUHM] turn my face away and look fixedly out of the window to hide my tears. I’m not sure why the music, so free of anguish and turmoil, has this paradoxical effect. But…[it has] to do with what Lester Bangs called the ‘intricate balm’ supplied by the music itself: calming, cleansing, gliding along placidly yet propulsively, it's a twinkling and kindly picture of heaven.”

Gloria Jones is at the wheel when Marc Bolan dies in a car accident at 29. Clean, self-propelling machines that they are, Schneider and Hütter travel from venue to venue by touring bike. By July 17, 1982, I have no taste for sloppy tragedy or fresh air utopia, but I crave, oh, how I crave, the inflection. How I ache for flourish.

Despite Soft Cell’s spoken aspirations to the likes of Kraftwerk, something is most definitely lost (or scuttled) in translation. There is no heaven in Soft Cell’s driving “Tainted Love.” I do not cry in the backseat of the station wagon (going nowhere), nor do I feel cleansed. Technically pure, I am scoured, too, by the scraping losses of the seventies, and broken enough to let in a kind of joy, even innocence, forged in ruin, sharp as Eliot’s shards, crusted in last night’s cocaine shared among last night’s friends and lovers at the Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret that is 1982, if I can make my way to the right dimly lit place, away from the basements and fluorescent sprawl and mall-infested interstates of suburban paranoia. Love is all there is, teases the emcee through the greasepaint, and isn’t it resplendent, tainted through and through.

Touch me, Baby, please.

The author, left, and his friend Mark, shortly after college graduation, during their St. Elmo’s Fire era.

Irene Cooper is the author of Found, crime thriller noir set in Colorado, Committal, poet-friendly spy-fy about family, & spare change, finalist for the Stafford/Hall Award for poetry. Writings appear in Denver Quarterly, The Feminist Wire, The Rumpus, streetcake, Witness, & elsewhere. Irene is co-founder of The Forge writing program & Blank Pages Workshops. She teaches in community & supports AIC-directed creative writing at a regional prison, & lives with her people & Maggie in Oregon. irenecooperwrites.com

The Situation that the Bass is In: david griffith On “It Takes Two” and the Birth of the Author

For the first 47 years of my life, I believed that Mike Ginyard, aka MC Rob Base, was celibate.

In 1988, when Base and his childhood friend DJ EZ Rock’s, single “It Takes Two” dropped, I was thirteen and did not know of anyone, besides, the adults in my life, and maybe Tanya, the hot as hell sixteen-year-old daughter of my paper route client, Mr. Yarbrough, who was having sex.

And so, every time I listened to “It Takes Two” in the basement of our split-level ranch in Decatur, IL, on my father’s capable system—Pioneer receiver with 5-band graphic equalizer, JVC CD player, with a hand-built 70s HeathKit turntable, and Pioneer speakers with 15 inch woofers—the line “...don’t smoke buddha can’t stand sex [sic], yes…” struck me funny.

The only people I knew that did not have sex on principle were the priests and nuns at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, and I would come to find out years later that I was even wrong about that.

I was naive about a lot of things—was thirteen-years-old and living just off a cul-de-sac in the heart of the heart of the country in the Soybean Capital of the World—but especially sex and drugs. It wasn’t hard for me from context clues to understand that “buddha” was weed, but the syntax and flow of the line “don’t smoke buddha, can’t stand sess, yes” made it seem these were separate activities. Like, don’t drink, don’t smoke, what do you do?

Thanks to Urban Dictionary, now I know that “sess” is short for sensimilla, a word that I actually did know (even back then) due to uncles who exposed me at a young age to CaddyShack:

“This is a hybrid,” groundskeeper Bill Murray lisps. “This is a cross of Bluegrass, Kentucky Bluegrass, Featherbed Bent, and Northern California Sinsemilla. The amazing stuff about this is that you can play 36 holes on it in the afternoon, take it home and just get stoned to the bejeezus…”

At thirteen I had yet to smoke (or drink) anything that would send me into an altered state, unless you count RC Cola, but I was discovering that music did something to me—for me.

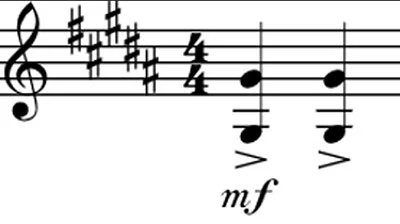

I had been playing trombone since the 5th grade and had just that year joined the Mound Middle School jazz band, led by Mr. Jim Walker, a balding, spectacled clarinetist, who led a Dixieland group that played street festivals and wedding receptions. Somehow, amidst all the distractions of middle schoolers playing grabass, Mr. Walker taught us the rudiments of swing: “Doo-va-Doo-va-Doo-va-Doo-va,” he would drone, tapping his foot, and twirling his index finger, coaxing us forward into that new musical, alchemical idiom in which two eighth notes become a dotted eighth, sixteenth.

There are times even now, 35 years later, that I will spontaneously begin singing the melody to Glenn Miller’s “A String of Pearls” or Count Basie’s “Shiny Stockings,” big band standards that groove with a deceptively deep, almost tidal force.

And yet, for all my exposure to some of the swingingest, most danceable music ever written, dancing is not something I did. My family, nor any family I knew, did it. Maybe my dad would have a little too much Cold Duck on Christmas Eve and would get to bouncing around and twirling my mom, but that was it. We were Midwest Catholics (my mom was actually raised Seventh Day Adventist, a sect that frowns upon dancing) with no strong ethnic identity—some Irish, some Welsh, some German and Dutch—but not a high enough concentration of any of these to influence the food laid on the table, or our holiday rituals.

In the absence of these influences, I was a blank slate. I would lay on my back on the basement floor and listen to Zeppelin and Edgar Winter albums from my parents collection but also a stray Donald Byrd fusion album, and a completely whacked out Emerson, Lake, and Palmer album with a cover featuring battle tanks in the shape of armadillos; I sang in the choir at the Methodist church because that’s where many of my friends worshiped; I did a brief stint as a trombonist at our Our Lady of Lourdes because the music director discovered a Vatican II hymn that squarely ripped off Brubeck’s “Take Five” called “Sing of the Lord’s Goodness,” which was excruciating because all I could imagine while playing was the angelic, crystalline alto sax tone of Paul Desmond.

But by far the biggest influence on my sense of musical possibilities was my neighbor, Chip. Chip was 4 years older, had Tony Hawk bangs, and a fake radio station, WPIG, in his basement.

WPIG was basically a podcast 30 years before podcasts were a thing. We had a whole crew of guest DJs: my younger brother would sometimes show up and be allowed to choose a few tracks, Chip’s girlfriend, who I would later date after Chip went off to college, appeared on mic a few times under the alter ego Lois Lane—even my friend Cory, whose voice and reporting now regularly appear on National Public Radio, had a cameo.

Each show took up the space of a 90 minute cassette. Most of the 90 minutes was music, but what made it different from your run of the mill 80s mixtape was that we would take turns introducing the tracks in our best, most sincere imitations of the slacker college radio DJs broadcasting from the local WJMU: And that was [long pause] 10,000 Maniacs [long pause] “About the Weather,” I would say in a high pubescent voice, trying desperately to sound world weary.

Every third or fourth song there would be a recap: You…just…heard INXS “Mediate,” the Beastie Boys “Brass Monkey” and [long pause] U2 “Bullet the Blue Sky…” There were segments where we read articles directly, verbatim from Rolling Stone or gave a run down of the Top 40 albums, but there were also skits and interviews with invented characters from the neighborhood, like the hard of hearing Granny Fudrucker, played by my brother, in a caterwauling dragged-up Terry Jones falsetto.

It was in the summer of 1988, in Chip’s basement, WPIG station headquarters, that I first heard “It Takes Two.” By that time, the song had already peaked. It spent 3 weeks in the top 40 beginning in mid-April and then spent 19 weeks slowly sliding down the top 100, but continued to hold steady on the dance charts through 1989, ascending as high as number 3. In 1989 Spin magazine ranked “It Takes Two” as the no. 1 single of all time. In 2021 Rolling Stone ranked “It Takes Two” no. 116 on its “Top 500 Best Songs of All Time.” Eventually, it would be certified Platinum many times over.

I didn’t know any of that at the time. I just knew it was unlike anything I’d heard before.

It’s one of those songs, like Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks,” or George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog” or Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” where there’s a rhythmic tease, a few bars to set the tone; a little prelude to get your attention. But the first several bars of “It Takes Two”--a sample from the Galactic Force Band’s 1972 “Space Dust”--isn’t so much a tease as a pronouncement; it’s giving prelude to a grand space promenade; like you’re at a block party with hundreds of people: grills are smoking, the sun is beating down, everyone is out and looking good; everything and anything is possible, and then, out of nowhere a portal in the sky opens and this synth fanfare erupts, but not one of those soaring, medieval fanfares with piercing trumpets, but a bottom-heavy, descending line pulling you down, pulling you in like some kind of trance-inducing deep space transmission, like some kind of tractor beam; something you’ve heard and felt standing wedged between Galaga and Space Invaders in the crowded mall arcade. You just can’t place it. No one can. But before you can think a voice enters your consciousness, a voice that has been there since before time, waiting. The booming voice of god speaks the song into existence:

RIGHT ABOUT NOW…NOW…NOW

YOU ARE ABOUT TO BE POSSESSED[A platform bearing two men in tracksuits—deus ex machina style—lowers them to the stage]

BY THE SOUNDS OF MC ROB BASE

AND DJ EZ ROCK…ROCK…ROCK…HIT IT!

The basement was carpeted and had a low drop ceiling. At the far end, just outside the laundry room, was a tiled dance floor backed by a mirrored wall, so without even trying, the acoustics were bright without being muddy, like the school gyms where Chip and I would later DJ. The bass hummed in the tile and shimmied in the marbled mirrors, sending vibrations up through my feet, into my chest and teeth. It was a good, alive feeling.

And that was just the first 12 seconds of the song.

What follows is one of the most memorable downbeats in music history: a low frequency bass kick that cannot be produced on any actual acoustic instrument because it’s not a sample—a digital recording of an actual drummer playing an actual kick drum—but a completely synthetic sound created by the Roland TR-808 drum machine. The beat hits, then rumbles—sound engineers call it “decay.” Only the 808 has that specific kick and decay; a gauzy thud, like a heartbeat.

And then, we all know what happens next, a funky, janky, clattering Mardis Gras march of synth snare, hi-hat, and clap track:

Whoo! Yeah! Whoo! Yeah!

It takes two to make a thing go right

It takes two to make it outta sight

I didn’t know it at the time, but these few bars snatched from Lynn Collins’ 1972 feminist funk-soul hit “Think (About it)'' is one the most famous and most sampled breakbeats in all of hip-hop. It’s hard to hear, but down there underneath all that synth is Jabo Starks, the drummer for the JBs, James Brown, the Godfather of Soul’s, backing band

Starks’ meticulous 8-on-the-floor style isn't showy. He was known for holding it down so others could be free. JB bassist Boostie Collins and trombonist Fred Wesley have both said as much. “I could just blow free,” Wesley said in one interview. Starks’ impeccable groove-making allowed others to not just be fully themselves, but the confidence to transcend their limits.

Which is exactly what Rob Base does when he finally begins to rhyme:

I wanna rock right now

I'm Rob Base and I came to get down

I'm not internationally known

But I'm known to rock the microphoneBecause I get stoopid, I mean outrageous

Stay away from me if you're contagious

'Cause I'm the winner, no, I'm not the loser

To be an M.C. is what I choose 'aLadies love me, girls adore me

I mean even the ones who never saw me

Like the way that I rhyme at a show

The reason why, man, I don't knowSo let's go, 'cause

It takes two to make a thing go right

It takes two to make it outta sight

The circumstances in which I first encountered “It Takes Two” are comically different from the circumstances in which the song was created: Decatur, IL, a sprawling prairie city (47 sq. miles), population 94,000; Central Harlem, over 100,000 people crammed into 1.4 square miles. But what was similar is that the late 80s was a time when everyone was learning how to copy, sample, and remix. I didn’t own turntables or a mixer, like DJ EZ Rock, or even any LPs of my own, but I had a dual cassette deck hooked up to a CD player and a brick of blank Maxell tapes, a VCR and a closet full of Kodak brand VHS tapes with bright orangey yellow labels. I made mixtapes for friends and, later, girlfriends. I learned to program our VCR so that I could record episodes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which came on every Saturday night at midnight on the local PBS station.

For a school project on Romeo and Juliet, my buddy Joe and I figured a way to connect two VCRs together to create what we considered to be masterpiece of video art, in which we intercut video of our classmates performing scenes from the play with clips from Yo! MTV Raps and Python-esque interludes in which we referenced inside jokes from Late Night with David Letterman.

When we weren’t making fake radio shows we were taking Polaroids of ourselves skateboarding and then cobbling them together into a handmade zine, employing the photocopier in the business office of the local Kmart, where Chip’s dad was the manager. There we taped the Polaroids to pieces of paper, captioned the images with a Sharpie and then laid them against the warm glass, a process that turned the washed out color photos into grainy gray-scale tableaux depicting me and my brother and Chip ollying off curbs and leaping from (unseen) stacks of landscaping ties to create the impression of catching massive air, a la the Tom Petty “Free Fallin’” video.

This is all to say that I grew up making copies of things, sampling things, then stitching them together with other things. But I did not grow up dancing.

There was a lot of chin out head nodding, eyebrow raising, and maybe some slight up and down shoulder action, and toe tapping, but otherwise the arms, legs, and hips did not get involved. Dancing always seemed so risky, so deeply personal—so visible. The copying and sampling and stitching and dubbing was out of sight—all anyone saw was the finished product. They didn’t see me sitting in my parents basement late at night obsessing over the sequence of songs, worrying whether the selections were too bald, my emotions and intentions too easy to spot.

This all changed with “It Takes Two.” Prior to that summer, the big hip-hop hits weren’t things you could even play at the Mound Middle School dances. I mean, there was LL’s “Going Back to Cali” and Kool Moe Dee’s “Wild Wild West,” songs you could hear on the radio, songs that even our teachers would admit to knowing, but we all knew the real stuff wasn’t for public consumption. I’m talking NWA, 2 Live Crew, Too-Short, Ice-T, Slick Rick, even Public Enemy was seen as too political.

If you wanted to listen to any of that you had to know someone who could drive—an older brother or sister, or a neighbor, and then you could catch a track or two while catching a ride home from school, take in lyrical scenes and situations that my white, Midwestern, thirteen-year old self had never even dreamed.

But in the end, the lyrics weren’t the thing that stuck with me—it was the beats and the bass pulsing through my back, rattling the windshield and trunk lid. This wasn’t the Bronx, where hip-hop and Rob Base were born, or Harlem where he moved in 4th grade, met DJ EZ Rock, and first heard the Crash Crew playing at block parties, this was Montgomery Hills, Decatur, IL, a quiet warren of hilly, curving streets punctuated by cul-de-sacs. There were no block parties, no one used their porches or stoops for anything more than pumpkins and rustic benches that no one ever sat on. No, the music was confined to basements and cars—stereos that were only played loud when parents weren’t home, kicker boxes locked inside the trunks of Honda hatchbacks, volume turned down when we rounded the corner into the neighborhood.

“It Takes Two” was an exception. It played well with others, and not plays well with others in a palatable Fresh Prince way, but in a way that brought generations together. I remember my mom, a Baby Boomer, who came up with the Mamas and the Papas, James Taylor, and the Moody Blues, coming down into the basement, catching the beat, bobbing her head, and half joking, half not, shouting along with the “Whoo! Yeah!” break.

At the time I didn’t know where that sample came from, but I have to believe that my mom, who graduated from college in the early 70s would have known Lynn Collins’ “Think (About it).” Maybe she recognized it, maybe she didn’t. It doesn’t matter. What matters was that it made her move, made her shout.

Flash-forward a few years to post-football game dances in the galleria of Stephen Decatur High School, and “It Takes Two” became the great leveler of the dance floor. All of a sudden, it wasn’t just the cheerleaders and the pom squad out there doing “Da Butt” or “The Percolator” which required a startling, cold-sweat inducing level of coordination and ass-moving. Rob Base had come to democratize the breakdown. When he commanded us, on the count of three, to “1, 2, 3…Get loose now!” We all listened. It became something we could all do—we needed to do—a welcome release from the 1-2, 1-2 foot shifting of slow dancing to “Running to Stand Still” or Sinead’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

The popularity of “It Takes Two” shouldn’t be so much of a mystery, and it definitely shouldn’t be seen as a fluke, or a fad. What Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock did was tap into the very essence of hip-hop itself: Only fifteen years earlier, August 11, 1973 in the Community Room at 1520 Sedgwick Ave in the Bronx, DJ Kool Herc, an eighteen-year old immigrant from Jamaica did something no one else had done before. He’d been watching the crowds at dance parties, and noticed what got people on the floor were the breakbeats, the funky, groovy instrumental sections between choruses. So, DJ Kool Herc, using two turntables, like the disco DJs in Manhattan (to keep an uninterrupted flow of music going), began mixing together just the breakbeats: a break from James Brown’s “Give it Up or Turnit Loose'' would slide into “Bongo Rock” by the Incredible Bongo Band, then back to Brown, and then over to Babe Ruth’s flamenco guitar inspired “The Mexican.” The result? A dance party where the DJ kept the audience guessing, finding more and more unexpected combinations of rhythms, and flavors, and genres, which led to more people on the dance floor and, eventually, later, a method of laying down a rhythmic foundation for MCs to rap over. Herc called this the “Merry-Go-Round.”

“It Takes Two” doubles down on the “Merry-Go-Round” technique, looping Lynn Collins’ “Think” (“Whoo! Yeah!”) break over and over and over throughout the track, then layering on top an 808 confection: A deep bass hit on the one and a clap track pattern that is a direct rip-off of the 1984 disco sensation “Set it Off” by Strafe, a beat that all but obscures Jabo Starks’ snare and hi-hat, so while you can’t hear it, you can feel it down there.

Which is what makes “It Takes Two” so singular, so itself, a classic, not some gimmick. If you really listen you can hear and feel all its antecedents; all the layers of rhythm. You can hear the whistle of the drum major summoning the band in the Mardi Gras parade. You can hear the hi hat and snare of Jabo Starks, who grew up in Alabama listening to the loose but military style of the Mardi Gras parade drummers. You can hear the tambourine from the original Lynn Collins track, and on top of that—doubling it— the ricocheting high hat and clap track of Strafe; all these generations, motivations, and situations of sound on stage at once.

In other words, what makes “It Takes Two” so infectious, so readily, irresistibly danceable, is that it’s basically a five minute long Frankenstein’s monster of a breakbeat.

Again, I say this all as though I knew it then back in the summer of 1988. All I knew was what it did to me; how it made me move my shoulders from side to side; how it put a hitch in my hips; what the bass did to the air around our bodies.

But there’s more.

In a 2018 interview with Rolling Stone—four years after DJ EZ Rock’s death—Rob Base revealed that the creation of “It Takes Two” took place over the course of one night in a studio in Englewood, NJ, right across the George Washington Bridge from Manhattan. They didn’t have an album yet or a record deal, so their manager told them: “Yo, we need to get in the studio, knock out a song or whatever.”

And so they did.

They started listening to records, throwing around ideas, eventually putting on Ultimate Breaks & Beats Volume 16, the latest installment in a series of albums put out by Bronx DJ “Breakbeak Lou” Flores for use by other DJs, in which he compiles jazz, funk, and rock tracks with especially tasty, groovy, funky, or original sounds and beats. Side one of volume 16 features tracks by the Commodores and Marvin Gaye. Side two, as luck would have it, features Lyn Collins’ “Think” followed directly by the Galactic Force Band’s “Space Dust.”

Rob Base told Rolling Stone: “Basically, it’s just like, it was right there. The hit was right there in our face. And we just took it.”

If there is a spirit to every age, then that might just be the spirit of the late 80s:

It was right there, and we just took it.

That fall, my 8th grade year, Chip started a DJ business. Not exactly his business partner, I was enlisted to help schlep equipment and page CDs and cassettes. I only really remember one gig: a dance at John’s Hill Middle School, and those memories are vague and dark: a steamy gym, the smell of Drakkar Noir, Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” and Technotronic’s “Pump Up the Jam.” But what I remember clearly is the moment when I pressed play on the CD player and that godly voice filled the room: “Right about now…” There were screams followed by dozens of tweens in pegged jeans sprinting from the dark edges of the gym onto the dance floor. Up until then I had been a spectator, but at that moment I became hooked on the power of making others move their bodies.

Now, nearly thirty-five summers later, I am clearing the fog from the bathroom mirror and preparing to shave my face. “It Takes Two” is blaring from the iPhone on the back of the toilet tank.

As I lather my face, I begin to move and rap along, “...my name’s Rob, the last name Base, yeah, and on the mic I’m known to the freshest…” and as I bring the razor down my jaw I think of Chip. I haven’t seen him since—I have to think really hard on this—the summer of 1996 or 97, but we’re Facebook friends, so I know he's out in Portland and a DJ.

I’m thinking of him because last night as I was writing I wondered if he had any of our old WPIG tapes—I have one, but can’t find it anywhere—a casualty of so many moves.

And so I messaged him on Facebook:

Hey, working on this thing about “It Takes Two” and WPIG…You have any of those tapes still? And to my surprise, he responds: Have to take a look.

A few minutes go by and a photo pops up in the chat box. It’s Chip’s hand holding a vinyl copy of “It Takes Two.”

A few more minutes go by. Chip writes back: Damn. I think any tapes that old got melted in my apartment fire in Decatur in the 90s…

I return to the keyboard and re-read all that I’ve written. I am having that spectator feeling again. All these words and sounds are just sitting there on the page pointing to something, pulling me toward something: a desire to be both in my body and loose of it.

I get up from the table, walk to the stereo, and push play on the CD player:

RIGHT ABOUT NOW…NOW…NOW…

I turn the volume up as loud as I can stand it. My old speakers crackle a bit, but then settle in.

YOU ARE ABOUT TO BE POSSESSED…

I’m looking for that exact frequency.

BY THE SOUNDS OF…MC ROB BASE…AND

I want to feel it again for the first time—in my feet, my chest, and teeth.

DJ EZ ROCK...ROCK…ROCK…

HIT IT!

Dave Griffith is the author of A Good War is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America (Soft Skull).