the sweet 16

(6) everclear, “santa monica”

mutilated

(7) THE PIXIES, “WAVE OF MUTILATION (UK SURF)”

608-551

and plays on in the elite 8

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 19.

Watch the World Die: melissa faliveno On “Santa Monica”

I am still living with your ghost

Lonely and dreaming of the west coast

Not long ago, a writer I know from Portland called Everclear “the Nickelback of the 90s.” I was horrified by this news. Growing up in small-town Wisconsin, where the influence of the coasts hit us late, if it hit at all, I loved Everclear with everything I had in my hard Midwestern heart. As far as I knew, they were as cool as it got.

In 1995, the year Everclear’s first major-label record, Sparkle and Fade, was released, and “Santa Monica” hit alt-rock airwaves across the country, I was twelve. At the time, my favorite records were Green Day’s Dookie and the Offspring’s Smash. I had the t-shirts, oversized and plastered with album art, purchased at Hot Topic in the West Towne Mall in Madison. It was here, twenty miles from my hometown, that I would weave my way on any given Saturday from that black-lit den of lava lamps and mass-produced alternative culture to Claire’s, spinning wire racks of cheap yin-yang rings and yellow smiley-face necklaces on ball chains and black cords, to that most hallowed mecca of the mall: Sam Goody. And afterward, just across the parking lot, Best Buy.

In 1995, and in the years to follow, these big-box stores and their endless rows of cassette tapes and CDs in shiny jewel cases were all I knew. This was where I bought my Dookie and Smash; my Sixteen Stone and Tragic Kingdom; The Downward Spiral and Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Where I bought Garbage’s self-titled debut and Everclear’s Sparkle and Fade.

Just a few miles away was Madison’s legendary Smart Studios, where Garbage and Everclear recorded those albums, at the very same time. The same studio where Nirvana recorded Nevermind. But I didn’t know this yet. I didn’t know who Butch Vig was, or what a producer did. I didn’t know the thrill of recording to tape, creating a document through music. I didn’t know about scenes, or zines, or house shows. I didn’t know the sticky floors of dark clubs, or gig posters tacked to dive-bar doors. I didn’t know there were cooler record stores too—dusty places run by punk kids and old hippies, where I would learn to thumb disaffectedly through used vinyl before I even had a record player. I didn’t know that two of my favorite records had been made in a city I loved, which I would soon call my second hometown.

“Santa Monica” is a song about a hometown. It’s a song about leaving the place you come from and wanting to go home, even when you know you can never really return. And maybe what I mean is it’s a song about nostalgia—about longing for a place, and a time, that looks better from a distance.

It’s a simple song, in some respects: basic chords, nothing fancy. Its complexity lies in the nuance, the slow build of tension and release. The heart of it, though, is the man who sings it.

Alone in my apartment, I work on the chords. It’s not an easy song to sing and play at the same time, but I’m trying. My guitar is plugged into a Fender Prosonic, a 90s tube amp made to be turned up loud. It sits beneath my living-room window, below a 1970s Fender Bassman. It’s a handsome stack, silver-faced and vintage (because the 90s, somehow, is vintage too) but it’s out of place here. It belongs where it once lived, in places where loud music is made. Before friends left town and bands broke up, before a rehearsal space was torn down. Before the music, like everything else in New York, went away.

I play low, at first, to not piss off my neighbors. But in this year of pandemic half the neighbors have left, and no one has moved in below us. So I turn up the volume and play to the living room, empty except for my cat, who hides beneath a chair because she hates the guitar, but who, unlike everyone else, doesn’t leave. I turn the distortion up too, till the notes are dirt and fuzz. I always sound better this way, the further I get from clean.

It’s no surprise, really, that a band like Everclear was uncool in a place like Portland in the 90s—the kind of scene whose depths of cool I can’t even fathom. It was the next Seattle, or so the old alt-weeklies tell me, though I suspect it was a scene more like Madison’s at the time—small and weird and eschewing stardom, doing its own thing. A band that wanted to make it—a band that wasn’t even from there—was perhaps the furthest thing from cool.

“Everclear remain out in the cold among Portland’s band circles,” wrote the Rocket in 1994. A year later, Portland’s Willamette Week crowned frontman Art Alexakis “the most hated musician in Portland,” and “the most unpopular musician in Portland.” These words were echoed by the Portland Mercury fifteen years later. It’s a title, and a sentiment, that stuck.

“We basically got every door shut in our face here in Portland,” Alexakis told the now-defunct music site Addicted to Noise, in a 1995 interview titled “Loser Makes Good.” “‘Cause we weren’t from Portland. If you’re not part of the clique, it doesn’t happen. And we did happen, without any help from those people, and they resent the hell out of us.”

The tension between art and commerce (see what I did there?) is an old one, but I would wager it was most acute in nascent indie scenes in the 90s, that slacker’s beating heart of the grunge era. A band that did the damnable—sign with a major label, hit the charts, tour the world—were not just uncool; they were sell-outs.

But when you grow up without much money, you learn early that you can, indeed, buy yourself a new life. That working hard, and selling things—whether it’s paper or car parts or music—is a way to stay alive. No one knew this better than Art Alexakis.

“We were one of the first, really, to jump to the major labels because it wasn’t really deemed very cool,” he told Oregon Live in 2015, at the twentieth anniversary of Sparkle and Fade. “Me, I just wanted to support my family.”

With apologies to a city I like a lot, it’s hard, as an outsider, to think of Portland in the 90s and not imagine Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen, dressed in plaid, hanging out at an indie record store on Hawthorne (how am I doing, Portlanders?), rolling their eyes at some bleach-haired kid asking for the new Everclear. It’s hard not to feel the kid’s shame as she scurries out the door—a feeling I’ve had in record stores so many times, including a few weeks ago, when I finally bought a copy of Dookie on vinyl. For every record, every band, every song you hold up as the pinnacle of cool, there is some much cooler kid who will tell you it sucks.

“We weren’t the hipsters,” Alexakis said. “We never have been.”

Being an outsider—being uncool, being weird—is something Art Alexakis writes about a lot. He’d been an outcast long before moving to Portland, in 1991, and by then had already begun to wear his weirdness like a badge, like a chip on his shoulder, like armor.

“I was always treated like an outcast by other kids at school,” he told Addicted to Noise, which in 1995 named Everclear Band of the Year. “Their parents would find out where I lived and they’d send me home. And I couldn’t go to those kids’ houses anymore.”

Alexakis was born in Santa Monica, California, on April 12, 1962. When he was five, his father left (and did sometimes send his son a birthday card with a $5 bill), and the family moved to a housing project in Los Angeles. When he was twelve, his brother died of a heroin overdose and his girlfriend committed suicide using the same drug. Not long after, he attempted suicide by jumping off the Santa Monica Pier.

By age thirteen he was shooting heroin, cocaine, and crystal meth. At twenty-two, after spending time in juvie, he overdosed. He got clean, and after a few failed bands, a failed record label, and the first of three failed marriages, he moved from San Francisco to Portland, in the hopes of starting over. On public assistance with a kid on the way, he started Everclear—named after the alcohol, which he calls “pure white evil”—a drug that will fuck you up more than most but has a pretty name. (Anyone who has taken flaming shots of Everclear, like I did in college, understands this.)

In 1993, they put out an EP called Nervous & Weird. Their first full-length, World of Noise, recorded in a basement for $400 and released on Portland’s indie label Tim/Kerr, followed the same year. In 1995, Sparkle and Fade marked the band’s jump to the majors; they signed with Capitol, solidifying their reputation in Portland as opportunists, selling their collective soul to the devil.

Still, the AV Club gave the record an A- and Rolling Stone a coveted four stars. More than twenty years later, in 2017, Willamette Week—the same publication that gave Alexakis his infamous title—called Sparkle and Fade “the best album ever recorded by a Portland band.”

With my big black boots and an old suitcase

Do believe I’ll find myself a new place

In late 1994, Art Alexakis was twenty miles away from my hometown and having a bad time. In the two weeks spent in Madison recording Sparkle and Fade, he couldn’t sleep. He was plagued by panic attacks, having nightmares about falling off the wagon. One night, he woke up in a sweat and wrote “Strawberry,” a song about a relapse that made it on the record.

“It’s my biggest fear,” he told Addicted to Noise, “and by facing it like that and putting a face on it I think I deal with it a little bit.”

Everclear in Madison, WI, after recording Sparkle and Fade

As a writer, it’s something I’m still learning: to put your fears into words—by recording them as an album, or an essay, or a book—is a way of letting them go.

While Alexakis was recording Sparkle and Fade downstairs at Smart Studios, its cofounder Butch Vig was upstairs producing the debut album of his own band, Garbage. Madisonians claim Garbage with an unparalleled fierceness; Shirley Manson of course is Scottish, but Garbage is a Madison band. I like to think, in some small way, that we can claim Everclear too. The record they made in Madison would launch the band to international fame. It went gold, then platinum, and spent thirty-five weeks on the Billboard charts. Harder, punker, and far more grunge than the polished pop-rock of their later records, it was an album that embodied the alternative ethos of the time. But it was also doing its own thing. Alexakis, whose background was one of cowpunk and country, sounds a little more Tom Petty than Kurt Cobain. But he also sounds unlike anyone else. When he sings—and the dude can sing—you hear something true in his voice. And that, I think, is part of what makes this record so good: It’s a document of a life. It is, in the end, something real.

“Sparkle and Fade was kind of my escape route,” he told SPIN in 2015. “It was dealing with a lot of stories about people going through tough times and trying to find their way out of it, trying to find the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Of “Santa Monica,” he told the same magazine in 1996: “I knew the song was a good song, but you can never tell when a song is going to connect. This song, for some reason I’ll never know, connects.”

I was not a cool kid. I was, in fact, a hairy only child with a lisp. In 1995, when I was in middle school, girls started getting pretty and I just got hairier. I attempted to disguise my weirdness in band t-shirts and flannel, but it was no use. On the bus, bullies spat in my frizzy mane and called me “beast.” I pulled loogies out of my hair-sprayed bangs. In high school, I was a curious combination of band nerd, art kid, and athlete. I was never popular—I played the wrong sports, wasn’t blonde, and, despite having lived in the same town my whole life, wasn’t considered from there. In a Midwestern farm town, my Italian father (and our shared hirsute bearing) marked me an outsider. But such is the remarkable brain chemistry of the band nerd—who marches across a football field on Friday nights in their spats and feathered hat, convinced their soaring trumpet lines are admired, not mocked—I eventually stopped caring so much.

In the deeply uncool tradition of small-town and suburban kids in middle America, where the only mixtapes pressed into my hand were recorded from alt-rock radio, I often found the early albums, the cooler albums, after I found the hits. I found Kerplunk after Dookie, Dude Ranch after Enema of the State. Like loving Nirvana after I loved the Foo Fighters, I was obsessed with So Much for the Afterglow before Sparkle and Fade. And I’m not sure about this (memory can be an excellent tool of self-preservation), but it’s possible I found Everclear—along with Garbage and Radiohead—on Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo+Juliet soundtrack.

Regardless, I found Everclear when I needed them. Or maybe, as is the way of music, especially when you are young, Everclear found me. When I first heard “Santa Monica,” on Madison’s alt-rock radio station, WJJO, I heard, in Art Alexakis’s voice, things I’d never heard spoken aloud. He sang about depression and isolation and suicide. He sang about addiction. He used words like “poor” and “white trash.” He sang about things I was starting to understand, but had thus far carried alone. And in a time when to be earnest was perhaps the most uncool quality, Art Alexakis pulled his heart out of his chest and gave it to us.

So Much for the Afterglow was my album of anthems, thirteen tracks of catharsis. I drove around my hometown at night, dreaming of escape. I played Afterglow, then Sparkle and Fade, in my Chevy Cavalier, its speakers blown out so badly the whole car rattled. I turned the volume up anyway. I drove out to the country, rolled the windows down and let in the smell of cow manure, and sang along with Art, who sang about how trauma has a way of making you weird. It’s a deep kind of weird, he tells us—the kind that doesn’t let go, that you carry your whole life. But that, if you’re lucky enough to stay alive, you might learn to wield like a weapon, or make into art.

Walk right out to a brand new day, he sings in “Santa Monica,” and by this point in the song he’s screaming, insane and rising in my own weird way.

I’ve played in a few bands, but I’ve never fronted one. I’m not sure I’ve ever wanted to. Like most altos, I’m all harmony and never melody. I like it there. What I love about making music, and what I miss, is creating something collectively.

My band’s rehearsal space was in a warehouse in Greenpoint, between a motorcycle garage and the Gutter, a bar and bowling alley where we played few shows. It had a weird smell, the bathroom was heinous, and we made music there for eight years, playing in friends’ bands and our own. We were a collective, kind of, in a way I didn’t realize then. Two years after the building was torn down, the lot is still empty. There’s a high-rise going up next door, but where our space once stood is a graveyard of broken cement, the remnants of walls that once held music. I walk by sometimes and look into the plastic scaffolding window, then press on past the places we used to drink—the Diamond, Jimmy’s—that are gone now too. In a year spent living with so many ghosts, this walk feels particularly haunted.

The year before we released our record, our bandmates left Brooklyn. They left, as people do, for places where they’d find more space, have families, make new lives. My partner—our frontman—and I stayed.

But the previous summer, in 2017, before we knew an era was ending, we went to see Everclear. The show was my birthday present, and the four of us went to Irving Plaza on a weeknight. Everclear had played the same venue in 1997, on the release of Afterglow, when we were all in high school. This was the twentieth anniversary tour. Our bassist and I had connected over Everclear, reminiscing at practice about deep cuts like “White Men in Black Suits” and “Pale Green Stars.” I said, at least once, that I wanted to cover an Everclear song someday. I thought we had all the time in the world.

On that warm night in June, Everclear played to a sold-out crowd. Mostly made of people like us—thirtysomething and giddy with nostalgia, very far from cool. Art’s voice was raw and plaintive and breaking, just as it had been twenty years before. We stood in the crowd, packed in and sweating, leaning close to shout in one another’s ears, our lips close to skin, the slick bodies of strangers pressing against us. We drank $15 beers from plastic cups, and we spilled some on ourselves, and our shoes stuck to the floor, and the hum of the amps rattled in our teeth, and we danced around like kids, and we sang along to every song, as if no time at all had passed.

I just want to see some palm trees

I will try and shake away this disease

Like pretty much everyone on the planet, I’ve been sad lately. I spent much of the past year alone, in the shadow of disease, haunted by old ghosts and new ones. It would be so easy, I’ve thought, to find that old oblivion; to swim out toward the breakers and let them pull me under.

Some days, music keeps me afloat. When I started thinking about this song, and what I might say about it, I remembered an old idea. What better way to inhabit a song—to feel connected to it again, like I did when I was young; maybe discover something new about it—than to play it? What better way to tell you how it makes me feel? I asked some friends if they wanted to record a cover of “Santa Monica.”

“I’ve been waiting twenty-five years for someone to ask me that,” one said.

We recorded the song ourselves. After a night of practice, we spent a Saturday in a rehearsal space not unlike the one my band once had, and ran a motley collection of mics into a multitrack recorder. A jumble of cables snaked across the floor. I’d forgotten what it felt like to be in a hot room with carpeted walls, making something with other people.

Historically, I’m self-conscious about the way I sing. My voice is weirdly low, my mouth moves in a strange way. Sometimes, on soft esses, my lisp comes back. As when I play guitar, I prefer distortion—afraid of what I’ll sound like on my own. I always stand too far from the mic.

But this time, I got up close. For the first time, I stood in front and sang the lead. I laid down my guitar lines, then turned to vocals. On my last take, I screamed it more than I sang it. For the outro, rather than take Art’s iconic ohhs and yeahs and whoas myself, we recorded gang vocals. We sang wearing masks, screaming together into one mic. I listen to what we made—faster, looser, a little more punk than the original—and I like what I hear. It sounds like what, at its essence, a recording is: a document. Not just of sound but of energy, of a feeling, of a moment in time. When I listen, maybe what I hear is catharsis.

We can live beside the ocean

Leave the fire behind

Swim out past the breakers

Watch the world die

I’ve never seen the Pacific Ocean. At least not up close. I’ve never been to L.A. either, unless you count Anaheim, which as far as I can tell is made entirely of strip malls, Disneyland, and the Mighty Ducks. Growing up in a place where we called lakeshores “the beach,” where the closest we got to California was Pacific Sunwear in the mall, the west coast was a fantasy. A place where kids rollerbladed in short-shorts and tube socks, ice cream dripping down their arms. It was MTV’s Spring Break, a season of Real World. It was a place that seemed, to my cold, landlocked heart, like paradise—a place no one ever leaves. When I left Wisconsin, I moved to the east coast in no small part because I was sure I wouldn’t stay.

I can’t write about “Santa Monica” without mentioning the photos my friend sent me last spring from L.A. The sky was orange. She said she was afraid to leave her house, not just because of the virus, which was just starting to take hold in L.A., but because the air was full of ash, poison in another way. That it might fill her lungs, or the lungs of her daughter, or of her son, who was still inside her and would be born in July. The sky, she said, was on fire.

In New York, where I’ve somehow lived for twelve years, I think of last summer, when the ash reached us here, our own skies hazy and orange. Now, I look out my window at a gray and endless winter. I see a brand-new building in our backyard. It’s been done for months, but one has moved in. It’s a hideous thing, made of floor-to-ceiling windows and cement that blocks out our sun. The lights burn all night, illuminating empty rooms—a ghost ship that never had life inside. And I can’t help but wonder, if we could do the things “Santa Monica” suggests—if we could shake away this disease, if we could leave the fire behind, if we were to swim out past the breakers and watch the world die, what might we find in its place?

We often talk about the importance of writing from a distance—when we’ve had time to heal, when retrospect helps us make sense of things. But lately I’ve been more interested in writing from inside a struggle, a still-fresh wound. When we don’t know how we’ll make it through, or what waits on the other side. When time hasn’t made a feeling fade. Whether it’s music or essays, maybe writing from a place of uncertainty, of fear or rage or grief, can help us find a greater truth. Sparkle and Fade, “Santa Monica,” are like that.

“So Much for the Afterglow feels like the work of a man who’s dealt with his demons and is ready to dispense wisdom,” the AV Club wrote in 2015. “Sparkle and Fade follows someone in the midst of them, a flawed figure who wants to be better but can’t follow through. The latter almost always makes for more compelling art, if only because the stakes are infinitely higher.”

Art Alexakis has been called a jerk, a dick, an asshole. He has said, “I am Everclear. Everclear is me,” a sentiment that, understandably, has pissed people off, not least former bandmates Craig Montoya and Greg Eklund, who were with him when the band got big. But Art Alexakis has also been called “the nicest musician in Portland.” Friends whose bands have opened for him offer similar reports. I think maybe he’s just an artist, a complicated human, who turned his pain, his trauma, his weirdness, into something we could feel.

“It’s not the band we relate to,” the AV Club writes. “It’s the heart beating at its center.”

I didn’t listen to any Everclear records beyond Afterglow. I heard some singles, but never bought another CD. I’ve listened to a few tracks off Alexakis’s solo record, Sun Songs, released at the end of 2019, but it’s a hard record to hear. Not long ago, Alexakis was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. On the record, he sings of fear and death and disease—things he’s sung about before, but this is different. Now, he sings about the fear of falling apart, of a new disease he can’t shake away. At fifty-eight, though, his voice hasn’t changed much since he was thirty-three. And when I hear him sing these songs, I can’t help but hear “Santa Monica.” So many years later, he’s still trying to find the sun.

In 2012, Alexakis founded Summerland, a music festival named after a song on Sparkle and Fade and composed entirely of alternative bands from the 90s. The festival has been called, derisively and not, a “90s nostalgia tour.”

“Liking stuff from the 90s is really about nostalgia,” Alexakis told Diffuser in 2015. “And I think a little bit of nostalgia is a healthy thing.”

Nostalgia is a funny word. From the Greek -algia, or “pain,” and -nostos, “return.” In the ancient epics like The Odyssey, Nostos means, specifically, “a return home from sea.” Some linguists have interpreted the word to mean, simply, a homecoming.

“Santa Monica” is a song about leaving, and it’s a song about going home. It’s a song about jumping off the Santa Monica Pier, but it’s not a song about dying. It’s about swimming out to sea, past the waves that might pull us under, to find what might exist beyond them. About watching a world on fire die behind us, but looking to the horizon with the hope. It’s about looking back, too—toward the places that made us, that once held us, that we long for even though they nearly killed us, and seeing both darkness and light. Maybe even perpetual summer.

“Santa Monica,” Alexakis once said, “it’s just about—I was in the rain and I grew up in the sun.”

There’s a reason I haven’t listened to Everclear’s later stuff. I heard it got too poppy, yes, that it recycles the same old groove. But this is not the reason. In the 90s, when I was twelve, then fourteen, then sixteen, Everclear was more than just a band. They—and what I mean is Art Alexakis—spoke to me in a way that nothing had yet. They spoke of things I was struggling with then, that I’m struggling with still. When I was most alone, “Santa Monica,” and Everclear, found me. And maybe this is the nostalgia talking, but I prefer this song, these records, this band—this more-than-band, this beacon, this catharsis, this shock of connection, this beating heart, this hand reaching out in the darkness and pulling us into the light—to exist as it existed then, and where it might live forever, in the globulous glow of a lava lamp, suspended in some golden sunlight of the California coast I’ve never seen.

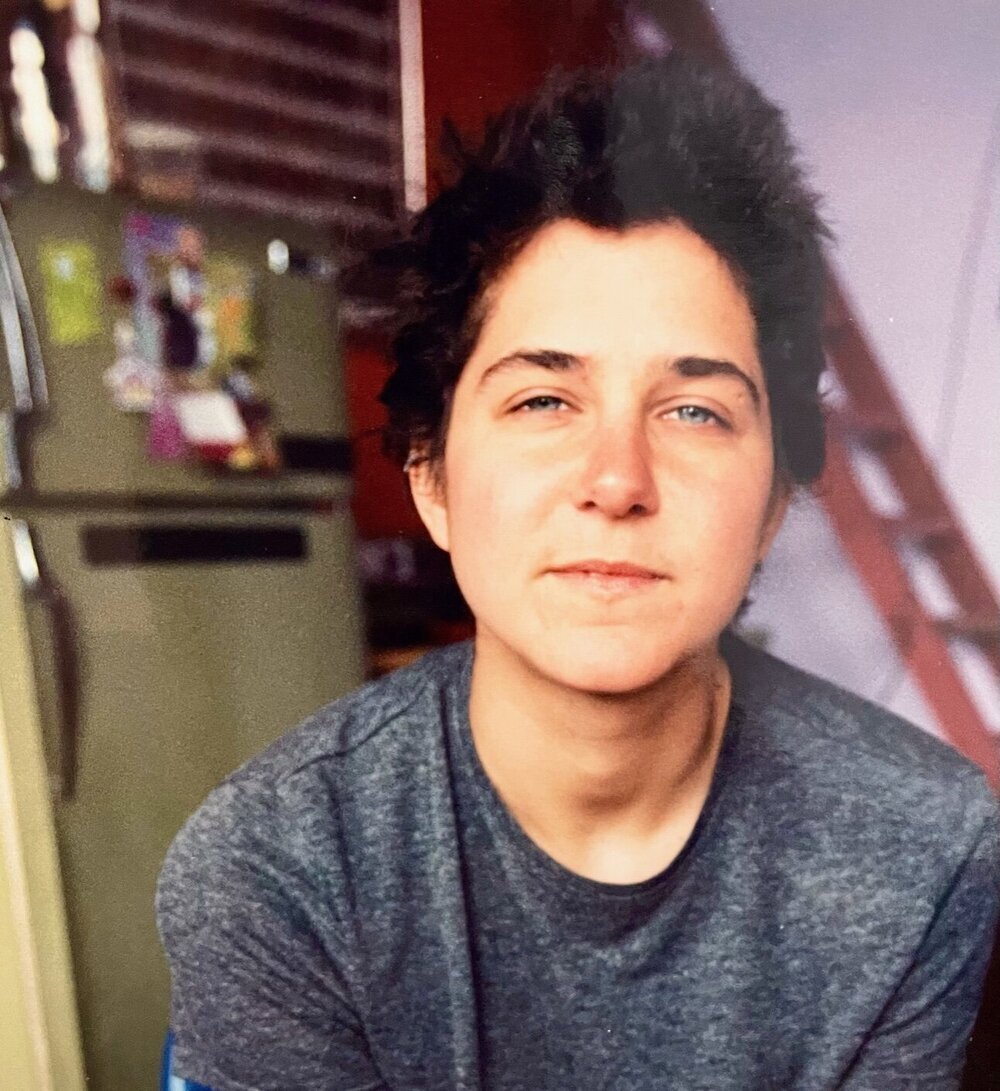

The author, age twelve, in 1995, the year “Santa Monica” was released.

Melissa Faliveno is the author of TOMBOYLAND: ESSAYS, named a Best Book of 2020 by NPR, New York Public Library, O Magazine, and Electric Literature. She is the 2020-21 Kenan Visiting Writer at UNC-Chapel Hill, and her wardrobe has not changed much since 1995.

A MUTILATED LIFE OR REALLY GOOD FICTION: STEPHANIE MANKINS ON ”WAVE OF MUTILATION (UK SURF)”

It starts with a kick. A wet kick, drenched in reverb. Then the snap of a snare.

BOOM-BOOM-CRACK. BOOM-BOOM-CRACK.

BOOM-BOOM-CRACK. BOOM-BOOM-CRACK.

The bass sends in a string of single notes so low

DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA-DA,

That we’re surprised when the next ones are even lower.

DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH-DUH.

We’re pulled down, wading through ten million pounds of sludge from New York and New Jersey. It’s a soft sludge, comforting, and we sink back into it like an old, familiar chair and ride it through to the end of this long, long day.

The strumming of an acoustic guitar fades in. It’s a ramp that launches us into the full song made complete by a haunting melody picked out on an electric. We’re awash in tremolo, wavering in time with the beat. We’re being prepared by magicians to receive the enigmatic lyrics of this fucked-up lullaby, sung in a breathy voice:

Cease to resist, given my goodbye

Drive my car into the ocean

You think I’m dead, but I sail away

On a wave of mutilation, a wave of mutilation

I was home from college on winter break the first time I heard the Pixies. There were seven or eight of us standing around my parents’ dingy suburban living room drinking Milwaukee’s Best—a truly unspectacular swap meet of bad roommate stories and new music finds—when someone asked if I’d heard the album Doolittle. I shook my head; I hadn’t even heard of the band. Jewel cases were shuffled, a cd was lifted from the flimsy plastic tray and another set in its place.

For someone else, someone much older, maybe, it might have been merely a young band’s sophomore effort, but for those of us straddling adolescence and adulthood, it was a seismic shift. Suddenly, our lives were as extraordinary as we’d dared hope they were, our moment in history as seminal as we’d always felt it could be. No longer were we me and you, sneaking cigarettes in your beater, moving pieces around a chess board we’d never master, earning minimum wage at Corn Dog 7 in the mall north of Dallas. We were gigantic.

The album’s third track, Wave of Mutilation, moves quickly with an intensity typical of many Pixies songs, but as the languid UK surf version proves, its power isn’t tied to tempo. If anything, the slower pace allows us to dive deep into the broodingly surreal and morbid existentialism that is the first verse. According to Black Francis, these four lines are about the 1980s phenomenon whereby foundering Japanese businessmen would commit murder-suicide—driving themselves and their families off a dock and into the ocean. Pretty gruesome stuff, yes, but I wonder—does it matter if you know what the lyrics mean, or where they come from?

Fast forward thirty years: what matters to me now isn’t exactly what mattered to me then, music or otherwise, which is something I attribute directly to becoming a mother. Having kids doesn’t diminish the importance of music, but it definitely rearranges priorities. Or maybe music is merely easier to lose sight of when faced with the more pressing demands of small humans: warm food, snacks, clean clothes, snacks, or replying to the urgent email from the school nurse who’s threatened to bar my daughter from virtual school unless I send in her immunization records immediately. Did I mention snacks?

Before I had children, music was all about me and my experience. Not that I didn’t marvel at its beauty and power, but I was always searching for what I could take from it. What could it do for my own music? How could knowledge of this or that aspect of this or that band elevate my standing among peers? What knocks me over now is realizing that there are whole musical worlds my kids don’t know about. There’s so much I sometimes feel like I can’t play it fast enough—songs and albums and bands that shaped my life—and the best part is that it has nothing to do with me. At least, I’m not looking to gain anything from it, not in the same way. I love to see their reactions, how one band will thrill them while others don’t seem to make an impression at all. Or it’s even simpler, a single moment: I can call out, Cease to resist, and one, if not both of them will answer back, given my goodbye. Depending on the mood, we may sing the next line, and the next, or even the whole verse, ending on wave of mutilation, something not one of us can easily define.

I hadn’t really given that phrase too much thought before I started this essay. I didn’t need to. The song’s fragmented, evocative imagery coupled with its singular sound was powerful enough to capture the raw angst of my late-teenage years, a vulnerable age when music tends to bore its way into your DNA. After that, the song and everything it encompassed were mine, and not something I needed to continue questioning. The same way I don’t think to ask why the sight of a slow-building thunderstorm—all blacks and blues and grays in constant collision—hovering above acres of tall, skinny pine trees comforts me. The same way I don’t wonder why sweet iced tea and salty fried okra always and forever belong to summers in east Texas.

Even so, wave of mutilation? What the hell is that?

My sister says that human existence can be thought of like waves in the ocean—each life one wave; each life a brief expression of a timeless entity too vast to comprehend. We are, every one of us, made up of the same stuff as everyone else. I like this analogy. It wouldn’t have meant much to me thirty years ago, but now it’s reassuring. My individual worries, the problems that threaten to overwhelm my day-to-day, are not unique to me. I am not alone.

The next step is a simple mathematical equivalency: If a wave is a life, then a wave of mutilation is a life of mutilation—or, a mutilated life. We all have our wounds, some of us more than others. Some of these wounds fade with time, but others leave us permanently scarred. If the scars are small or well-placed, we cover them up and get on with it. But if there are too many to hide, or they’re too large to disguise? What does it take—how many cuts—to render an entire life irreparable, mutilated beyond recognition? How damaged does your life have to become for you to no longer want it?

A few weeks into my first semester of graduate school, I arrived to my “Craft of the Essay” class and was met with the news of David Foster Wallace’s suicide. The mood was somber and many were shocked, though if you’d read even a little of his work, you couldn’t have been too surprised. Depression, suicide, and the agonizing mundanity of life figure prominently in all of his fiction. The conversation continued around the table as more students arrived, the word ‘tragedy’ thrown about as if it were a given, indisputable. While it’s almost always true that a suicide is a tragedy, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes it’s the life that’s tragic, and the suicide is the only response, the only way out.

I can’t say I was saddened by his choice, not exactly. I was sorry that his life was so painful he decided it wasn’t worth living, but there’s a difference. I couldn’t articulate this difference immediately and it took some time to process, but in the end, I was relieved. I felt relief for him. His family and friends were grieving the loss of him personally, that I understood. The literary community at large, on the other hand, was grieving the loss of what could have been—assuming that had he lived, he would have continued to create phenomenal art—but I couldn’t. Not then. It seemed selfish to even contemplate whether someone’s suffering was worth what that suffering could produce.

And it was his suffering that produced his fiction. He and his characters may have inhabited different worlds, one real and one not, but they were equally dark. Wallace once said, as if speaking directly to this connection, “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.” Popular music—rock, grunge, whatever—may not be fiction per se, but it is a fiction, and the best of it, like Wallace says, is about what it means to be human. Or, as in the case of ”Wave of Mutilation,” maybe what it means to fail, to give up being human.

There’s more to being human than suffering and failure, though: enter Wallace’s definition of really good fiction. In an interview with Larry McCaffery, an English professor at San Diego State, he said, “Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished, but it’d find a way both to depict this world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it.”

Can we see these possibilities in “Wave of Mutilation?” I was discussing this with my fourteen-year-old daughter the other day, and when I told her how Francis came up with the first verse, her gut reaction was horror followed by a resounding No! But the character in the song is not necessarily the same as the real-life businessman who killed his family and himself. Given the second line, You think I’m dead, but I sail away, you could be forgiven for deciding our character doesn’t die, that to sail away on a wave of mutilation is to accept that life is suffering and then continue to live, even if it’s a mutilated life, even if that mutilation is self-inflicted.

The second verse, and the song’s only other lyrics, is equally ambiguous.

I've kissed mermaids, rode the El Niño

Walked the sand with the crustaceans

Could find my way to Mariana

On a wave of mutilation

Sure, the world of kissing mermaids and riding a climactic condition (El Niño) is fantastical, but no one said realism is the only kind of fiction that can be great. Children live in fantasy worlds, and maybe that’s the best way to deal with a crappy reality. Plus, Mariana could be a woman, and love is always hopeful. That is, until you learn that Mariana is a reference to the Mariana Trench, the deepest oceanic trench on the planet. It’s hard to argue that finding your way there could mean anything other than dying and sinking to the bottom of the sea. Then again, the character says he could find his way to the Mariana trench, not that he necessarily did.

Lucky for us, in trying to decide if the song meets Wallace’s criterion for really good fiction, we’re not restricted to the lyrics alone. Unlike fiction that exists solely on the page, the fictional worlds of songs are created by music as well, and in the Pixies case, nothing is more alive than their music. It’s alive not only because it makes you feel alive when you listen to it, or because it serves as a bridge to your former lives, but also because it’s widely acknowledged to be the starting point for the era of 90s guitar rock, influencing such bands as Radiohead, PJ Harvey, Weezer, Soundgarden, and Nirvana.

Whether Wallace’s fiction succeeds in depicting a world that is both dark and includes possibilities for being alive and human, I can’t say. In the very least, it’s beyond the scope of this short essay. But if you’ve found this to be true in his work, you’ve found it, and it’s yours. Be thankful. I’m only sorry Wallace himself never did.

Stephanie Mankins graduated from Brown University with a B.A. in mathematics, and from Sarah Lawrence College with an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction. From 1998-2004, she and her band, Adult Rodeo, based in Austin, TX, recorded and released four full-length albums: The Kissyface (1999, Shimmy Disc); Texxxas (2000, Shimmy Disc); Long-Range, Rapid-Fire (Four States Fair, 2001); and Tough Titty (2004, Four States Fair). In 2016, she finished a short documentary about her sister’s decision to get a cochlear implant, Do You Hear What I Hear?, which can be found here: https://vimeo.com/167353167 She lives in Brooklyn, NY, with her husband, two kids, and their dog, Iggy. She’s currently working on her first novel.