(4) joan jett, “crimson and clover”

finally got by

(4) joe cocker, “with a little help from my friends”

337-297

and will play in the championship

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Pacific time on 3/30/22.

david turkel on Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover”

“Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” —DuBeat-e-o, 1984

I’ve named the play “Crimson and Clover” because I don’t know what it’s about. I want people to make up their own meaning, the way they do when they hear that song. I want them all to think about something different that’s true for each of them.

It’s 1998 and I bartend in a place called Hell and Joan Jett’s version is on our jukebox. Or “little Joanie Jett,” as we call her—an homage to Alan Sacks’ trash film, DuBeat-e-o.

When I ask customers what they think the song means, they tell me a dozen different things, as if the title itself were a sort of Rorschach. One says the song is about a girl losing her virginity. Another says that it’s clearly about shooting heroin, the blood mixing with the “honey” in a syringe. Still another informs me that Tommy James—the writer of the song—was a born-again Christian and that the crimson represents Christ’s blood and the three-leafed clover, the Holy Trinity.

The lead actor in my play, Tom, was of draft age in December 1968 when the Tommy James and the Shondells’ version raced up the charts. He tells me the song has always been about Vietnam for him: “blood and land, over and over again.”

My play is about none of these things. Though it’s written in three acts, which could represent the Trinity, I suppose. And it has some sex and violence in it. Also heroin. And camel spiders. And St. Francis and surfing and the C.I.A. Mostly it’s about a billionaire named Arson (played by Tom) who wants to become the first man in history to cross the United States, coast to coast, entirely underground.

It’s my first play and I’ve been in therapy since I started it. I ask my therapist—a Jungian—if he wants to know anything about what I’ve written. He doesn’t. “Isn’t it like a dream?” I suggest. “Couldn’t that be useful?” But he doesn’t seem to think so.

Tommy James claims to have simply woken up with the words “crimson and clover”—a combination of his favorite color and favorite flower—stuck in his head. But that story was disputed by Shondell drummer Peter Lucia Jr., who co-wrote the song. For Lucia, the title sprang from the name of a prominent high school football rivalry in Morristown, New Jersey (where he grew up) between the red-uniformed Colonials and the green-Hopatcong Chiefs.

And so, oddly, even at the ground-zero of the song’s creation, there’s dispute over what the words signify. Almost as if they were birthed twining a spell of some sort—weaving mystery and confusion into the air.

On the Songfacts message board devoted to “Crimson and Clover,” contributor after contributor offers what each insists is its sole, incontrovertible meaning. Kayla from Dallas writes, “The song is actually about a beautiful girl with red hair and green eyes, get it?” Rex from the ‘Heart of America’ begins his post, “It really surprises me that so few people have this right” before launching into the most painfully halting description of coitus, like a squeamish father tasked with the birds-and-bees speech.

However the title came about, the story of the song itself is well-established, if no less magical. As Shondell keyboardist Kenny Laguna tells it, the band had just lost their chief songwriter and the guys were pushing Tommy James to find somebody new, convinced he didn’t have the chops to write a radio hit himself. Five hours later, James and Lucia walked out of the studio with the recording of “Crimson and Clover”—James having played every instrument except drums on the track.

He then took the rough mix to WLS in Chicago, where he spun it for the head of programming as well as a top DJ to get their impressions. At some point during the visit someone at the station pirated a copy, and by the time Tommy James had returned to his car the single was on the airwaves in its raw, unmastered form, being hailed by the DJ as a “world exclusive.” Before Morris Levy, the infamous mobster who ran the Shondells’ label, could intervene, “Crimson and Clover” was already a hit and on its way to its ultimate destination at number one on the charts. Many who heard it that holiday season in 1968, thought James was singing “Christmas is over” on repeat.

At a Christmas party in 1998, an inebriated dancefloor collision results in my girlfriend tearing her ACL. We’re too fucked up at the time to know what’s happened. But when I wake up the next morning, she’s there beside me, crying in her sleep from the pain.

She’s been cast in my play as Looloo, a twenty-five-year-old recovering heroin addict whom Arson meets touring a new hospital wing. Looloo is a patient there because she skied off a mountain in an apparent suicide attempt. So, it makes sense that her leg might be in a brace, we reason. Sometimes things like this just have a way of working out.

“Do the math,” Lon from Providence insists. “It is a poetic masterpiece...about a plaid skirt...the girl he had a crush on in school wore...hence the colors maroon (crimson) and green (clover), and then the pattern over and over..........”

My girlfriend and I are among the half dozen or so co-owners of Hell, where, until the accident, she was also a bartender. She’s the real reason Jett’s 1997 retrospective Fit to be Tied is on the box, and why we frequently holler out, in our best Ray Sharkey impressions, “Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” whenever it plays.

Sharkey portrays the title role in DuBeat-e-o: a movie director who’s on the hook to the mob for a new picture starring Joan Jett. In real life, director Alan Sacks (best known as a creator of Welcome Back, Kotter) had been hired to salvage botched footage from an attempted screwball movie based on the Runaways—the all-female, proto-punk band Jett founded with drummer Sandy West in 1975, just weeks shy of her seventeenth birthday. Sacks had fallen in with the L.A. Hardcore scene and his solution to the problem of trying to use bad footage to make a good movie, was to make an even worse movie about a megalomaniacal director’s fantasy of making a great one.

“See, I shot this film so that Joanie would come out looking hip enough to handle any situation. Understand?” DuBeat-e-o lectures Benny, the cough syrup-addicted film editor (played by Derf Scratch from Fear) whom he’s chained to an editing station at gunpoint. “I mean, that’s why I put her in every slimey, scummy situation of Mankind that I can think of, okay? I mean, the essence of my film—my film!—is that true talent, no matter where it comes from, has gotta come out—because it’s got fucking ENERGY! You understand?!...That’s why I’m the director! I got the vision, you prick!”

IMDB lists Jett as “starring” in DuBeat-e-o, but this is a Bowfinger-like deception, since she only appears by way of the archival footage Sacks was hired to edit, and as a picture adorning a wall in DuBeat-e-o’s seedy apartment. More accurately, Jett is hostage to the movie, her bottled image coopted to serve its baser designs; her ever-tough performance chops fronting the Runaways cut to look as if she’s delivering these efforts to please the leering countenance of The Mentors’ El Duce (who plays his slimeball self in the film).

And yet, perversely, it all works. Moreover, it works just as DuBeat-e-o, at his most deranged, said it would: Jett’s hipness—her ENERGY—rises above it all, untouched and unsullied. And the movie, either in spite or because of its many flaws (it’s really impossible to say which), truly exalts her.

In the 2018 documentary Bad Reputation, Jett—its ever-inspiring subject—avoids any mention of Sacks’s film by name, but merely shrugs it off as “some weirdo porn movie.”

Before I started tending bar at Hell, I knew next to nothing about Joan Jett, outside of “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll”—a single that peaked when I was eleven years old and inking “O-Z-Z-Y” across my knuckles.

I didn’t know about the Runaways or Jett’s affiliation with the Sex Pistols. Didn’t know that she produced the first Germs album and music by Bikini Kill. Or that she and ex-Shondell Kenny Laguna—her longtime collaborator and Blackheart producer—were forced to shill her hit-laden solo debut out of the trunk of Laguna’s car after it was turned down by twenty-three labels. In short, I didn’t know that Joan Jett was punk before punk and indie before indie.

But by 1998, not only do I know these things, forty-year-old Jett has recently turned up in a black-and-white commercial for MTV, flipping off the camera and sporting the close-cropped platinum-dyed hair that will become as iconic to that era as her black shag was to the seventies. She’s been going at it hard for more than two decades at this point, only to emerge looking fitter, tougher, sexier, more otherworldly than ever before, and I am becoming obsessed.

“And there was Joan in the black leather jacket,” Laguna says of their first encounter at the Riot House on Sunset Boulevard. “The way I remember it, there was razorblades hanging from it. And...I just never seen anyone like this. I was like, ‘Whoa! What is this?!’ And...I think I loved her right away.”

Ahhh, well, I don’t hardly know her...

“A little quiz for the Peanut Gallery,” posts Alan from Providence on Songfacts. “Crimson is my color and clover is my taste and aroma. What am I?” he asks, before adding, with a tacit wink, “And there is a reason Joan Jett loves this song.”

But I think I could love her...

Laura from El Paso concurs: “I have to say that when Joan Jett sings this song, for me it is impossible not to feel it takes on a whole new meaning. She is singing about ‘her’ and how she wants crimson and clover over and over.............”

And when she comes walking over

I been waiting to show her...

Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” arrests us, not only for those parts of the song she’s altered, but also for what she’s kept in place: the pronouns of the singer’s object of desire. Though Jett has said this decision was about preserving the integrity of the rhyme scheme, the seismic impact of hearing one woman sing so intimately to another—unprecedented on popular radio in 1981—can’t, and shouldn’t, be overlooked. Not because the choice scandalized certain listeners (I mean, seriously, fuck them), but because for many others this was a revelatory and liberating event.

As Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna puts it, “The first time I heard Joan I was in the car with my dad and it came on. It was ‘Crimson and Clover,’ and I heard that voice, and I was just like, ‘Who is this person?’ And then, when she would get to the pronouns and say, ‘she,’ I got really interested.”

At the same time, I think it’s important to take Jett at her word as a no-nonsense rock- and-roller simply working in the service of a great song. Certainly it’s true that, where rhyme was no impediment, she proved more than willing to make heteronormative adjustments. Case in point: her most famous cover off the same album, the Arrows’ 1976 tune, “I Love Rock and Roll”: “Saw her standing there by the record machine” became “saw him standing there.”

But what’s true in both cases is that Jett’s persona animates and subverts each narrative equally. Speaking for the eleven-year-old that I was when I first heard “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll,” it was a novel and noteworthy experience to be confronted by a sexually aggressive woman describing her recent conquest of a teenage boy in such tough, conversational terms. Like Hanna, or Kenny Laguna, I distinctly remember thinking, Who is this person?

Jett describes her own approach to inhabiting songs this way: “Part of it is having fun, and part of it goes back to...being able to do everything. When you’re singing songs about love and sex, you want everyone to think you’re singing to them. Whether you’re a boy, a girl, a woman, a man—whatever you’re into, I can be that.”

My, my such a sweet thing

Wanna do everything

What a beautiful feeling...

“The greatest voice you’ve ever seen”—that superlative from DuBeat-e-o—has never been showcased to greater effect than 1982’s “live” performance video of “Crimson and Clover.” At minute 1:28, Jett seems to be singing in harmony with her own eyeballs. Yes, sing the eyes, you know exactly what I mean... I would argue that as much as keeping the word “her” matters to this cover, the potency of Jett’s rendition hinges on her phrasing of the word, “ev-er-y-thing.”

What’s brilliant about Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” is the way she both queers and straightens the song. Gone is the drippy vibrato and underwater warbling which threatens to make the original a relic of Psychedelia. In their place, Jett and Laguna have punched up the guitars and amplified the dynamic interplay between the breathy, epiphanic verses and the riotous bounce of its instrumental breaks. In live performance, at the dramatic crescendo—Yeah!—Ba da! Da da! Da da!—Jett never fails to let go of her guitar and raise her arms fist high toward the audience. “Crimson and Clover” is an anthemic rocker, as she embodies it—a song about connection, celebration, ecstasy.

But what truly distinguishes Jett’s version from the Tommy James and the Shondells’ original, is that Jett actually knows what she’s singing about; Tommy James didn’t have a clue.

“People ask me what it means?” James told a Youtuber who calls himself the “Professor of Rock” in a 2019 interview. “Two of my favorite words that sounded very profound when you put them together. And just a three-chord progression, backwards.” For Jett, on the other hand, the meaning is clear. In Bad Reputation, she envisions the song from the perspective of the woman she’s singing to: “‘Oh my God, she’s gonna take me home and fuck the shit out of me!’ That’s scary!”

I don’t make this comparison to disparage Tommy James; cluelessness is possibly the single greatest feature of his music. He recorded “Hanky Panky”—his first number one hit and one of my all-time favorite rock-and-roll tunes—having only heard a garage band’s cover of the original and remembering almost none of its lyrics. His chart-topper “Mony Mony,” from March of ’68, cribbed its title off the acronym emblazoned atop the Mutual Of New York building, which loomed outside the window of James’ Manhattan apartment. In both cases, his ability to imbue nonsense words with infectious energy and devilish intentions earns him Kenny Laguna’s praise as “the Led Zeppelin of Bubblegum.”

With “Crimson and Clover,” however, James needed a song that would do the opposite— launch him out of Bubblegum’s playground on the AM dial and into the burgeoning FM market.

And while he loves to tell the story of how the title arrived in his sleep and how the song was a deus ex machina for his band (“I think my career would have ended right there with ‘Mony Mony’ if there wasn’t ‘Crimson and Clover,’” he told It’s Psychedelic, Baby in a 2013 interview), the real truth is that Tommy James had spent nearly two years clocking an impending shift in the musical landscape. At an earlier point in the same interview, he describes the moment in February 1967 when he heard “Strawberry Fields Forever” crossover to an AM Top 40 station: “That really left an impression on me.” A new audience was emerging for whom Pop’s infectious energy was not enough. They were hungry for something beneath the surface.

Or, at least, the suggestion of it.

Not to be outdone by the Songfacts sleuths, I have my own admittedly less romantic view of the real meaning behind “Crimson and Clover.” Whether consciously or not, the title is a “Strawberry Fields” analog. Red and green, verdant and evocative—Crimson and clover, over and over is Tommy James’s Strawberry fields, forever.

This suspicion only solidifies with a listen to the whole Crimson and Clover album, which wears the influence of that particular Beatles’ song pretty thin over its ten tracks. "Hello banana, I am a tangerine,” Tommy James sings at one point, sounding like a narc trying to bluff his way onto the Psychedelic school bus.

But look again at the same three songs: “Hanky Panky,” “Mony Mony” and “Crimson and Clover.” All three open on an image of a woman in motion. All three turn on a chorus of indefinite but suggestive meaning. What truly separates them, and what also separates Bubblegum from Psychedelia (“Sugar, Sugar” from “Mellow Yellow”) is that the former uses innuendo to hint at a song’s true meaning, whereas the latter employs it to the opposite effect— suggesting that the song’s meaning is deeply buried and perhaps not even fully available to everyone.

All of which is to say that, while Tommy James certainly knows how to inject a song with implied meaning when he wants to, with “Crimson and Clover,” he is deliberately trying not to say anything. It’s a masterpiece of indirection. Like a shell game with no pea.

Stage lights rise on a young man hanging upside down, his head in a bucket. This is the character of Jeffery, the surfer in my play. He’s been imprisoned in an unnamed country by fascist goons who have mistaken him for a writer. He hangs like this for a few beats, and then his interrogator enters and grabs him up by the hair. That’s when the soundboard operator cues the song: Ahhh...well, I don’t hardly know her...

Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover” kicks off act two of my play. This is the real reason why I’ve chosen the title—I want the song to feel like it’s stitched into the very fabric of the text, so that no one will mistake it for a directorial or sound designer’s decision. Like DuBeat-e-o, Alan Sacks, Kenny Laguna, Kathleen Hanna, I want Joan Jett’s bottled light to illuminate my dim interiors; I want to claim some of that impossible energy of hers for myself.

But my director has other ideas about the power source we need to tap into for our production. A week before we open, he introduces us to Robert, his guru—a professor from his grad school days. Robert speaks at length in a haughty British accent on the subject of “vibrating at a different frequency”—a discipline which he believes, once mastered, renders an actor utterly captivating to audiences.

We’re gathered in a circle where the only language we’re allowed is the single syllable, “bah!” and we’re instructed on ways to “direct our sound.” First, off one wall. Then two. Then off two walls and through the window out into the street, like a bullet ricocheting. Bah! BAH! “Put your bah into your chests,” Robert tells us. Bah! “Now into your stomachs!” Bah!

I’m afraid to even look at my girlfriend, there in her leg brace across the circle from me. This is everything I promised her theatre wasn’t. The total opposite of Punk rock.

“Now, put your bah into your left foot,” Robert, the guru, prompts me, dropping to his knees so that he can rest his ear just below my ankle.

“Bah!” I shout.

He looks up and says in earnest, “Don’t yell. It’s not about volume. It’s about putting your voice into your foot.”

The next day, he takes the cast to a mall, where, at full voice in front of the Cinnabon, he describes the milling shoppers as “dead people.” Our job as high priests of the theatre, he informs us, is to remind them all what it means to be alive.

When Tom tells the guru that he finds the mall patrons “electric,” he is banished from the inner sanctum. Meanwhile, my girlfriend has hobbled off with one of the other actors to get stoned in the parking lot.

Eventually, I too shuffle away in despair and embarrassment. The guru’s visit has cost us two thousand dollars and we can no longer afford the boat we need for the climactic third act scenes on the underground river. It’s just as well. I’ve lost all faith in my play by this point. All my big ideas have turned into mush. The monologues I was so proud of, despite all my actors’ best efforts, ring false and contrived.

There’s only one scene I care about anymore. Over the run of the show, it will be the only scene I consistently emerge from the wings to watch. I wrote it in five minutes and thought nothing of it at the time. It’s just a breakfast scene with the whole cast present. Everyone gathers in the kitchen, trying to start their day and pass the butter around the table. Arson and Bell, the scientist, discuss plans to launch his underground journey from the secret lab she runs beneath Mount Weather. Ed, the CIA operative, tells a crass joke to Looloo and Benedict—a psychic who’s recently been helping Arson communicate with the dead.

Jeffery is the last to enter. He’s been in bed for days, horribly sick from his ordeal. He’s shaky on his feet and not really certain where he is.

There’s something about the rhythm of this sequence I got right. The butter, the stray fragments of dialogue and competing conversations. The entrance itself, which isn’t clocked by everyone at the same time, so that it’s like a musical breakdown with all the instruments cutting out one by one. The particular quality of the silence that follows, as Jeffery stands there swaying, and Looloo slowly rises to meet him. There’s something about the way the actors have to extend themselves to fill the gaps in this scene; that’s where the life is, I’m starting to understand, in those gaps.

This is my first real piece of theatre. No one thinks twice about it but at least I’ve figured that much out. In performance, you don’t hardly know what you’ve written until someone else tries to make your words their own.

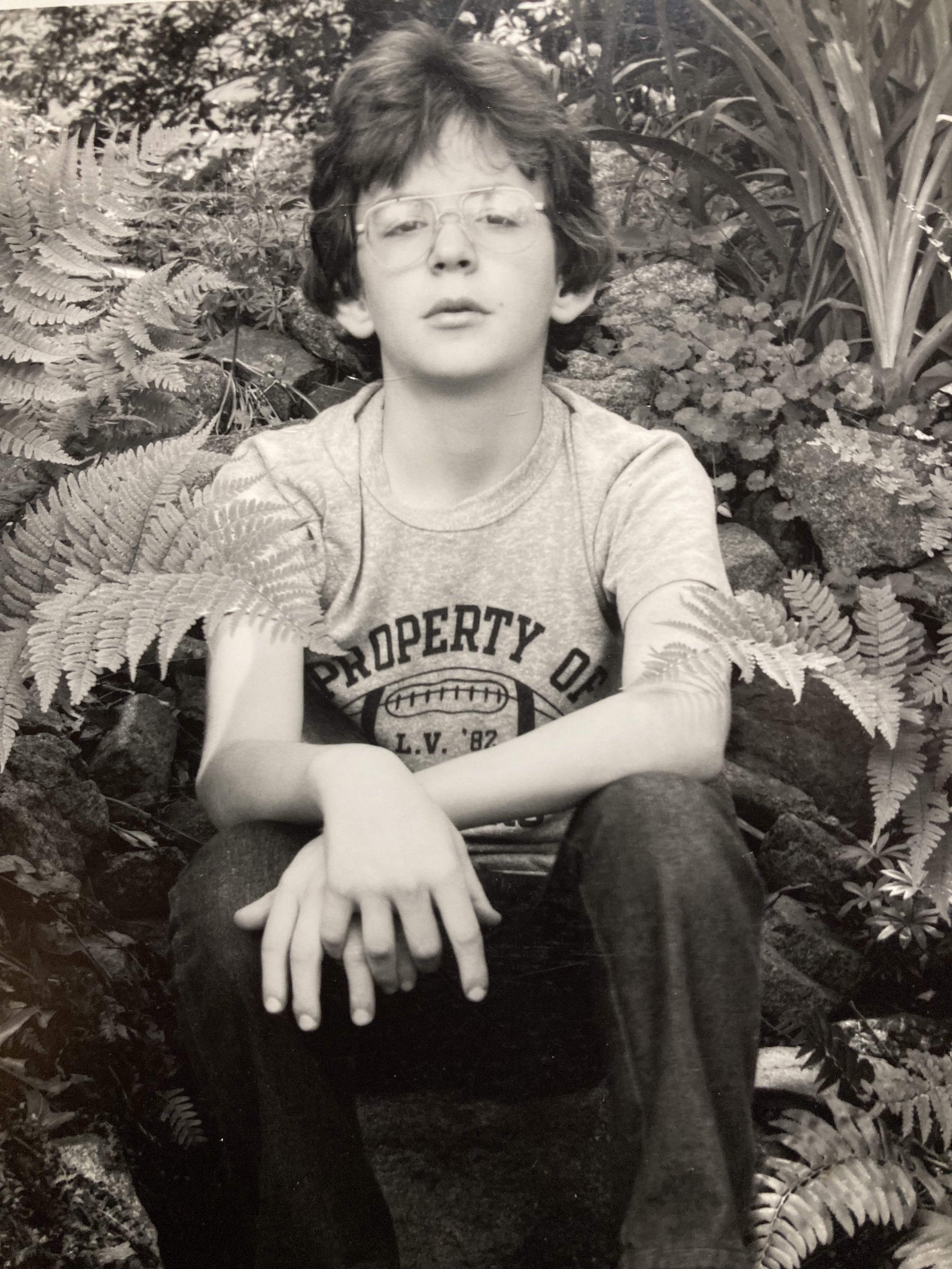

The author in 1982, the year Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” peaked at #7 on the Billboard Hot 100. Captured here in the wilds of New Jersey, without a clue in his mind that he is headed straight to Hell. And from there, eventually, Oregon. He will pick up bartending and playwriting along the way and would be pleased to know that he’ll one day land a gig writing about vampires for television.

SOMEBODY TO LOVE: KATIE MOULTON ON JOE COCKER’S “WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS”

What would you do if I sang out of tune?

Just imagine how tired he is—let us consider, first, the blessed exhaustion of Ringo Starr. Let us examine the mellow glory of that goodheart with the hangdog eyes. The weariness—not of the boss, the rallyer, the conductor or composer—but of the Steady One. The one who shows up, probably even on time, who sits mostly silent through the squabbles and trips and big bangs of the Beatle-verse. You could be forgiven for thinking he’s not paying attention; sometimes he is definitely not—he’s napping inside a high paisley collar. But as soon as the petty business and fucking-about is concluded, Ringo’s eyes open, and his wrists and ankles kick in right on time. Not flashy, but with a distinctive feel, a push-and-pull. The beat that reminds the others of their united frenzy in Hamburg, the days when they could still be a crack live act. The just-right flourish that assures the others they’re not doing the same old Beatles thing again. He can take a note. He’s been listening, but he doesn’t try to take the reins. He makes it go.

And then—what now?—they want him to sing. Ringo’s the one who rarely steps out for a tea or tantrum, who doesn’t have to record his parts in isolation. It’s true that in 1968, during the long White Album sessions, he’ll quit for three weeks, but for now it’s late March 1967, and Ringo just wants to go to bed.

Would you stand up and walk out on me?

This is the story of the first recording of “With a Little Help from My Friends”: For the final song added to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Paul McCartney and John Lennon had been crafting a song for Ringo as “Billy Shears,” the lead vocalist of the alter-ego band. Ringo had his own fans, and Lennon/McCartney tried to write one song per album for him to sing. Until this point, these Ringo songs had been almost farcical covers, like “Act Naturally,” or whimsical kid-friendly singalongs like “Yellow Submarine.” According to McCartney, “You had to write in a key for Ringo and you had to be a little tongue in cheek.” In a studio session that began at 7 p.m., the band did ten takes of the “With a Little Help” rhythm track before they had a keeper. Nearing dawn, the session presumably wrapped and a long photoshoot day looming, Ringo trudged toward the door. McCartney called out, “Where are you going, Ring?” Then Lennon and George Harrison joined in to cajole him into recording the vocals then and there. All four Beatles stood close together around the microphone, coaching and encouraging Ringo’s performance of the carefully designed five-note melody line. It took a few tries to make the octave-spanning leap to hit and hold that final off-kilter high note, but they got it. At 5:45 a.m., Ringo got to go home.

The next day, the Beatles shot the famous cover for Sgt. Pepper, then returned to the studio at 11 p.m. to record overdubs. Tambourine, guitars. Harrison, Lennon, and McCartney sang in unison the questions of the call-and-response lyrics and added sporadic harmonies. Then McCartney stayed to create the striking, meticulous bass parts, which Rick Rubin would later describe as “lead bass,” a funky through-line that adds a shadow to the straightforward tune. “With a Little Help” may have been truly a group effort; Lennon may have added the wit; and McCartney may have gotten the final say, but it’s Ringo who has used it to close most shows with Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band for the last thirty years—the theme song of a real-life bandleader in the end.

What do I do when my love is away?

When Sgt. Pepper dropped in May 1967, the album immediately belonged to everyone. Within days of its release, Jimi Hendrix opened his London show with a searing and playful distortion of the title track—with McCartney in the crowd. The album’s second song, “With a Little Help,” with its simple style, major key, community-oriented lyrics, and Ringo’s down-to-earth baritone, could be heard as a gesture of inclusivity.

But the album has mostly been perceived as a declaration of artistic separateness—an answer to Pet Sounds, a psychedelic hodgepodge of childhood influences and contemporary values, mixing vaudeville, music hall, Indian classical, tape manipulation, and avant-garde with a warm and innovative touch. It was understood as momentous in The Moment. Folks were hungry to mark the time as a turning point, to dose deeply in the Summer of Love, to see their hopes reflected and projected by pop heroes. Like the counterculture that embraced it, Sgt. Pepper was a concept album that circled back to itself. The truth is, you can never call a thing what it is while you’re still living inside it.

Does it worry you to be alone?

Before and during the Beatles era, there was a different public and artistic relationship to popular music; these songs were part of a shared lexicon, and peers frequently performed and re-recorded the hits. Interpretation and acknowledgement of lineage were common practices across folk, traditional, jazz, and pop standards, but less common in the rise of rock. From our twenty-first-century vantage, we’re so busy praising Beatles’ melodies that we forget that they were always riffing other people’s songs on the long and winding roads to their originals. We’ve accepted the Beatles as pop-music auteurs, and generations of songwriters have interpreted their later discography as a mandate to privilege originals and to take your work—and your pleasure—seriously.

How do I feel by the end of the day?

Friends, thank you for your patience! We’ve arrived now at Joe Cocker: the singer of the song in question, the Sheffield shouter, the performer who was often called the Greatest Rock Interpreter of all time.

But in 1968, the 24-year-old singer from northern England was unknown when he released, only a year after Sgt. Pepper, a cover of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends”—and hit instant success. The song went to the top of the British charts and became the title track of Cocker’s breakthrough album in 1969. (The Beatles never released it as a single.) This version—I hope you’re listening to it now—is a radical rearrangement of the original, made possible with a little help from Cocker’s friends: Jimmy Page (somewhere between the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin) on lead guitar, Procol Harum drummer B.J. Wilson, Tommy Eyre on organ, Chris Stainton on bass, and American soul singers Madeline Bell, Rosetta Hightower and Patrice Holloway lifting up the call-and-response. The arrangement shifts from the Beatles’ plunking 4/4 tempo into a 6/8 waltzing dirge. The song begins with a freak-out: an organ bubbling out of the black swamp of the cosmos, a rapid drum build that erupts into Page’s scorching guitar vamp. All goes quiet.

Then Cocker’s voice steps into the clearing. His voice is deep and dynamic. If it is gravelly, it is like a stone pitched into the dark to measure distance. If it rasps, it is the cracking of a canopy of branches. The voice growls and bellows, yes. But the voice also whispers, considers and colors each syllable, vibrates low and lays itself bare. It is all ache, ecstatic in its desperation. It shakes and blows. It emerges from Cocker’s mouth and leaves him blistered and shredded. Yet the performance seems effortless; the voice can’t seem to help it.

At some point in the performance, you realize that Cocker isn’t playing any instruments. But it feels like he is. Because Cocker emotes as he sings, and he seems to sing with his whole body. He shakes, grimaces, flails to the ends of his fingers.

“What happens when you give Ray Charles LSD?” said Glenn Gass, professor at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music. “[Cocker] does what a lot of us do at four in the morning when there’s a song we love: these spasms of emotion, playing air guitar. He took that age-old problem of ‘What do you do if you’re a frontman, and you don’t have a guitar?’ Elvis and Mick Jagger solved it their way, and Cocker just became the music.”

Cocker’s live version is the version. And there are many incredible, extended live performances preserved on video—from trippy black-and-white clips on British and German TV to the iconic rendition on stage at Woodstock. “With a Little Help” is the final song of the Grease Band’s set, and Cocker lets it rip from the first note—playing air guitar, and air drums, and air organ with rigid, intricately moving fingers. He sways and bangs his head and throws his arms around. He’s begging not to be left alone, making any deal he can against a foregone conclusion, and the breakdown is a triumph.

Are you sad because you’re on your own?

Friends, the times when I have felt most connected to other people, but especially to a room full of people, is deep inside a singalong.

It’s true I may have first heard Cocker’s “With a Little Help,” as so many of my generation did, accompanying the opening credits of the TV series The Wonder Years. But more than the grainy faux-home-reel footage, meant to inspire late-80s nostalgia for a suburban dream of what America was like in 1968, when I think “Wonder Years,” I think of the voiceover. I think of Daniel Stern, whose sweet nasal strains I love tremendously. When I think of Daniel Stern, I think of his first film role in 1979, as Cyril in the great movie Breaking Away, all lanky six feet, four inches stretched out against a limestone slab of a decommissioned quarry outside Bloomington, Indiana. Which sends me right back to Bloomington, where I lived some personally momentous wonder years, and where I was surrounded by friends who were always singing.

Karaoke was more than a pastime, a dare—it was a practice. Wednesday nights crammed into the Root Cellar, Thursdays at the Back Door. Nights when the bars weren’t hosting karaoke, we made our own. House parties revolved around a TV screen and a portable karaoke machine with two microphones. When the catalog ran out, we pulled up lyrics and backing tracks on YouTube. Sometimes we sang from the center, moving the coffee table to hit our knees at the climax; sometimes we sang horizontal, deep in the crease of the couch and a night that would last as long as we stayed where we were.

I know karaoke is polarizing, but I love it. If you step onto that humble stage, grip the mic tightly or tenderly, I will fall in love with you for the duration of your performance. It’s an act of radical vulnerability to stand up alone in a room of strangers and friends and sing—not because you’re musically gifted but because this is what you’ve all agreed to do together. To share what you love not by explaining it, but by carrying it through your body. And in every shared love, there’s shared risk.

I am not a strong singer, but I am a solid mimic. I am not an extrovert. I can hold a spotlight, even around a dinner table, for about three minutes before I get uncomfortable. In my karaoke days, I learned that the best approach was to work against my natural inclinations. Karaoke success lies in the singer’s level of commitment to the performance. That’s why you have to go alone, leaving even your non-singing self back at the table. The fastest way to get committed was to choose a song I knew in my spine—not a song I could comfortably take on, but a song that would take over me.

To paraphrase Mary Oliver, and yes, I believe she was writing about karaoke: The point is not to be good. The point is to go all the way.

Do you need anybody?

We started this thing with the original “With a Little Help from My Friends” because that song is the secret knowledge that Cocker’s cover spins around. Because covers are about convoluted and overlapping lineage, about how songs are passed throat to throat.

The ideal cover does not improve, does not dominate, and does not supplant the original. It may sound like an oxymoron, but the function and success of a cover song is how it uncovers. How it reveals the hidden capacity of a song in a manner that the writer or first performer could neither deliver nor predict.

Yes, the boldness of Cocker’s rendition is enhanced by the similarities he shared with the Beatles. He was a contemporary—only a couple of years younger than McCartney, a fellow northerner, a young white Brit profoundly influenced by Black American artists and traditions. But the power of this version is in its divergences transposed on our knowledge of the original—the listener’s ability to recognize them as changes even as they are shocked by the new. There’s this first irony: A simple melody written for the Beatles’ most modest singer is transfigured by the possessor of a world-class, powerful, versatile vocal instrument. Secondly, there’s a refutation of irony: McCartney said that songs they wrote for Ringo had to be “tongue-in-cheek,” but Cocker blasts through pretense with a howling, post-verbal earnestness. Where Sgt. Pepper was defined by the Beatles’ technical innovations and studio fussiness, Cocker’s “With a Little Help” is a raw jam, a moment-to-moment vocal reaction to the sound and fury. Less a performance, more a channeling. Cocker’s song is defined by its all-out aliveness.

[screams]

Let this be the part where we howl. Let this essay cradle a call and response. Let it illuminate the spot in the yellow wood where we could have gone in one direction but instead climbed a tree. Let it air-guitar so hard you feel the breeze from these windmills. Let it tap out this tense dance between the individual and the collaboration, the ego and the collective. Let it show its ragged seams. Let it tear out the stitches with its teeth. When we ask questions, let us take this spasm for the only answer that feels right.

Could it be anybody?

But to hear Joe Cocker, you have to hear Ray Charles. From the very start, Cocker’s singing style was compared to Charles, the pioneer of soul, the American singer, songwriter, and pianist known as “the Genius.” The music critic Henry Pleasants described Charles as a “master of sounds”: “His records disclose an extraordinary assortment of slurs, glides, turns, shrieks, wails, breaks, shouts, screams and hollers, all wonderfully controlled, disciplined by inspired musicianship, and harnessed to ingenious subtleties of harmony, dynamics and rhythm.” Here’s the part that sounds like Charles’ far-flung follower, Cocker:

It is either the singing of a man whose vocabulary is inadequate to express what is in his heart and mind or of one whose feelings are too intense for satisfactory verbal or conventionally melodic articulation. He can't tell it to you. He can't even sing it to you. He has to cry out to you, or shout to you, in tones eloquent of despair—or exaltation. The voice alone, with little assistance from the text or the notated music, conveys the message.

Cocker learned these approaches, learned what might be expressively possible, by listening to Charles. He learned so well that he never stopped being compared to Charles—or rather, never stopped being contrasted with Charles. Because the difference did matter to critics, to listeners—that Cocker was white and young from England, and that Charles was Black (and still young) from the American South. The dissonance was important to the narrative of Cocker as a performer—and perhaps also important to the pleasure in the listening, an added marvel of his talent—particularly, probably, for white rock audiences.

You can’t write about white rock ‘n’ roll stars without talking about the Black artists they emulated and Black traditions they drew from, or about the dynamics that reward cultural co-option. Of course, before they were auteurs, the Beatles cut their teeth playing Chuck Berry tunes and fanboying over Little Richard. They never stopped being excited about rock ‘n’ roll’s progenitors, rumbling through old favorites continuously during writing sessions and rehearsals, a safe and joyful zone they could still enter together. Even at the precipice of their power, when the band invited Billy Preston, their friend from Hamburg, into the Let It Be sessions, they discuss with excitement Preston’s work playing in Ray Charles’s band. Before Cocker sang a McCartney song in the style of Ray Charles, McCartney himself was trying to sing like Ray Charles.

This is to say that the question of appropriation was present in the earliest days of Cocker’s career. The dissonance of Cocker’s figure was important, but so was the agreed-upon perception—to these same presumably white audiences—that his interpretive style was cool, by which we mean acceptable.

You can read early critics contorting themselves to address it. In 1969, Rolling Stone wrote, “Cocker has assimilated the Charles influence to the point where his feeling for what he is singing cannot really be questioned.” In 1970, the New York Times determined, “In Cocker’s case, the obvious relationship his music bears to Charles’s is not offensive.” Critics seemed to be discerning whether his chosen mode was exploitative parody or tribute or honest expression. If Cocker hewed too closely to his influence, how honest could the expression be? It’s an old question, older than Elvis—Can I, a white man, embody the blues? Have I earned the right?—and it’s resulted in horrifying acts of erasure. (Yes, I’m certain that it happens all the time.)

These days, we think a lot about how influence can veer into appropriation. But I don’t think Cocker was singing the blues. On the first album, he took the contemporary pop songs of Bob Dylan, Traffic, and the Beatles, as well as a Tin Pan Alley number, and delivered them in an emotive, bluesy style. (One exception is “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” which was first recorded, memorably, by Nina Simone in 1964. In fact, on Simone’s album, To Love Somebody, released the same week as Cocker’s in August 1969, she also covers Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released.” In that battle of the covers, she won in a landslide.) The only tradition he is laying claim to is mass-market global pop. If we look at his catalog, his two other biggest hits—“You Are So Beautiful” (a slower re-working of Billy Preston’s funky ode to his mother) and “Up Where We Belong” (an inspirational ballad and the theme of 1982’s An Officer and a Gentleman)—are pure schmaltz. Like Adele, our current best-selling voice, Cocker’s true allegiance was to sentimental feeling, and he applied his instrument the only way he could.

Would you believe in a love at first sight?

Is it enough to be the singer of other people’s songs, in a voice you half-borrowed?

“As soon as I heard Ray Charles, I stopped listening to anybody else,” Cocker says in a 1987 TV interview.

In the clip, miraculously, Ray Charles is sitting in the chair next to him, laughing.

In 1960, Charles had his first number-one hit with “Georgia on My Mind.” The song was penned thirty years earlier by two young white men in Bloomington, Indiana: Hoagy Carmichael, the pianist/composer who would write many standards of the so-called Great American Songbook, and Stuart Gorrell, who became a banker after graduation and never wrote another lyric in his life. Charles didn’t write it, no, but that song, once he had hold of it, truly belonged to him.

In that ’87 interview, Charles doesn’t brush aside the comparisons—or what one artist owes to another.

“There’s a difference,” Charles says, “when someone tries to emulate you and it’s a poor copy. It’s another thing when you hear the person and his soul…Like a good writer who reads Hemingway; he doesn’t try to be Hemingway, he takes from him the good thing that he can use for himself. [Cocker] has taken some of the things that he’s heard from me over the years and put himself into it and made it fresh.”

Somehow, over the decades, the two musicians—dynamos of voice and interpretation—got to know each other, shared stages, tracing and resting on the webs that connected them. “When we sing together,” Charles once said, “it’s almost like we’re an extension of each other.”

I don’t know if Charles’s endorsement is a convenient reason to accept Cocker’s music and performance without further interrogation. There are questions we have to live with a while, that keep opening up inside us. But I think Cocker honored his influences and approached his interpretations with reverence and, critically, an awareness of what he was and was not.

What do you see when you turn out the light?

I can’t tell you, but I know it’s mine

That’s the center of the original song, the only lyrics that Lennon took credit for, the year he died. And those are the lines that Cocker fucks with the most. He sings it differently nearly every time:

I can’t tell you, but it sure feels like mine

I can’t see nothin’, nothin’, but it suuuuuuure feels right

I don’t see too much…but it suuure, it sure feels like mine

Recently, regarding the book of McCartney’s lyrics he edited, the poet Paul Muldoon said something like: poetry strives for a kind of perfection, it has to bring its own music—but lyrics leave a lot of space. This question, “What do you see when you turn out the light,” is the only lyric here where a yes or no won’t do, and where the stakes are high and lonesome, the only hint of unraveling darkness in the original. In those lines, and the way the drum hits the snare so hard at the end of the phrase, the swell of the backup chorus rushing to bolster the singer, Cocker uncovers desolation and consolation entwined.

Cocker’s producer Denny Cordell once described the singer like this: “Joe is a strange guy; he has no ambitions at all. He just likes to rock ‘n’ roll, and he has no dreams about how he could do it, because he could rock ‘n’ roll any way he wants to.”

I disagree; I think you have to have ambition to make your debut singing a song by the biggest band of all time in a style learned from one of the greatest singers of all time. But Cocker confounds because he never aspired to be the rock auteur; he was always, truly the Rock Interpreter. He asked questions of a piece of music, even if that question was, What is here for me to find? The world would be worse if he had never sung “With a Little Help from My Friends,” if he’d never wrestled its tensions to the surface.

So here are some more questions, these calls we’ve been sidestepping:

What is the point of all our close looking and hard listening?

What will it take for you to stay with us to the end, or until we go to sleep, or until we shuffle off this small stage?

Don’t you know I’m gonna make it with my friends?

Friends, you too must believe in the power of interpretation—to be here at the end with me. But ultimately, the Interpreter must remain a little on the outside. We know this. For all our analysis and our craft, we are separated from that first creative impulse. But we, the singers of others’ songs, the writers writing to other people’s music, we gotta believe that something meaningful can be made in this in-between. In our flailing hands, in a gesture made visceral, in praising the vast web of songs passed throat to throat. We have to believe it’s worthy, sometimes, to muster our small skill and limited air supply, and let what moves us move us.

Katie Moulton's rock-obsessed memoir Dead Dad Club is forthcoming from Audible in 2022. Her writing about music & culture has appeared in The Believer, Oxford American, No Depression, Consequence, Sewanee Review, The Rumpus, Village Voice, and other places. After seeing Ringo Starr's All-Starr Band in elementary school, Katie developed a deeper appreciation for the drummer, though he remains her least favorite Beatle.