second round game

(9) the birthday party, “release the bats”

SWARMED

(1) the cure, “the hanging garden”

209-203

AND PLAY ON IN THE SWEET 16

Read the essays, watch the videos, listen to the songs, feel free to argue below in the comments or tweet at us, and consider. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchvladness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 15.

Toward a Unified Theory of Goth*: chelsea biondolillo on "the hanging garden”

In 2007, a couple of English professors assembled a book of 23 “scholarly essays devoted to this enduring yet little examined cultural phenomenon.” They called it Goth: Undead Subculture in what I hope we can agree is a pretty academic attempt at humor.

Though long, this essay is no final word on goth. Pretending to know definitively what goth is feels pretty not-goth.

💀

While The Cure’s current status as goth’s house band is (still!?) up for lively debate on the internet and, one presumes, in absinthe bars and Hot Topics the world over, their presence at the start of it all is pretty undeniable. The band first formed in 1976—the same year as Siouxsie and the Banshees and Joy Division—and was performing on live TV by 1979, when Bauhaus released “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” The earliest Cure/Cure side projects were called “post punk” by many (including Smith himself), but by their second studio album, their sound was called “morose, atmospheric” and “depressingly regressive” by some critics—or, pretty goth, in other words.

💀

The first time I heard about The Cure was in 8th grade, 1986. I was fourteen. I was asking around at school to find out who Robert Smith was, because a boy I liked had said that if I liked Depeche Mode, then I must also like Robert Smith. I pretended to know who he was talking about at the time. The third person I asked said, “Do you mean the lead singer of The Cure?” And I said, “Oh, yeah. That guy.” But I didn’t own any of their music until Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me came out the following year.

💀

Robert Smith met Mary Poole at school when they were both 14-years old. He has said she's the only woman to be featured in a Cure video ("Just Like Heaven"), though it's not true. They were married in 1988 and are married still. There is something about this that feels at once not-very-goth but also like the most goth thing.

💀

The first time I heard “Hanging Garden” was a couple of years later. One of my close friends had been told by her Jehovah’s Witness mother, that she and I couldn’t hang out any more unless I agreed to do Bible Study. The first attempt was a disaster—five adults and two teenagers sat around a table and one person would read a short passage, and then the leader of the study would ask very basic comprehension-type questions, like “So, in that passage, what did Jesus say to Judas at the Last Supper?” I had a very hard time keeping a straight face, and told my friend there was no way I could make through another one.

Option B was one-on-one study with a “youth instructor” named Janet—because she liked “goth music” like me, it was hoped she’d be more effective at reaching me. I was surprised that being a gothic JW was okay, when anything smelling slightly occult, such as vampires or demons, or anything suggesting drug use were expressly forbidden by my friend’s mother for religious reasons.

“Janet says The Cure is okay,” my friend told me. “But not all goth music. Like, not Siouxsie.”

“Why in the world one and not the other?

“She heard demons in Siouxsie once when she was on acid. Before she was baptized.”

“No chance it was the acid, huh? Like, she thinks it was actual demons?”

“Well, demonic voices. I’m just telling you what she says.”

My friend also did acid, read all sorts of forbidden books and listened to all sorts of occult-themed classic rock. She was not a good JW, but she was adept at putting up to get along, in the hopes of avoiding her mother’s unpredictable and violent abuse. So that we could keep smoking cigarettes and weed together after school, I said Janet could come over.

💀

LA Weekly, in laying Los Angeles’ claim as co-center of goth culture, along with “the U.K.” (would Robert Smith let them have it, I wonder?), allow that “No one necessarily loves the label, and "goth" has come to mean different things to different people, but in general, as a music genre, it conjures a moody aesthetic and a sort of sinister, cinematic vibe. As a fashion statement, it is expressed by a menacing kind of glamour—black clothing, dramatic makeup, embellishments that reference both horror and religious iconography.”

💀

On her first and only visit, Janet, looking more drab than dark, brought a tape she’d made me with Pornography on side one, and Seventeen Seconds on side two. We politely argued for a half hour or so about dinosaurs and then she left. Though my friend tried to broker a couple more study dates, none happened.

💀

In 1982, Rolling Stone said of Pornography, “Their dense, punkish minimalism is as much the product of studio technology as of any notion of aesthetics, and their ability to wring emotional nuances from a droning guitar or an echo-laden drum is truly remarkable. Unfortunately, that trick is also the most overused one in the band’s tiny repertoire, and it tires quickly. It is all very well to express a lot with a little, but the Cure most frequently uses a little to express nothing, and the effect is numbing in the extreme. […] Pornography comes off as the aural equivalent of a bad toothache. It isn’t the pain that irks, it’s the persistent dullness, and that makes this Cure far worse than the disease.”

💀

“The Cure for what, though? Heh, heh, heh.”—many dads in 1987, probably.

💀

Robert Smith has expressed discomfort with being called goth. In a 2011 interview with The Guardian, he said “it's only people that aren't goths that think The Cure are a goth band … we were like a raincoat, shoegazing band when goth was picking up.”

And just last summer, perhaps because no one seemed to have read the earlier memo, he went a step further. When asked by an interviewer from TimeOut if the word ‘goth’ had anything to do with him he replied, “Not really! We got stuck with it at a certain time when goths first started. I was playing guitar with Siouxsie and the Banshees, so I had to play the part. Goth was like pantomime to me. I never really took the whole culture thing seriously.” It was a shot heard round the world: … Smith distances himself from the label ‘goth.’ … Smith Says He Doesn’t Identify as “Goth.” Noisey, a Vice music blog, had possibly the best rehash of the interview, headlined The Cure’s Robert Smith, Goth Royalty, Swears Yet Again That He’s Not Goth.

Smith elaborated, “It’s just a theatrical thing. It’s part of the ritual of going on stage. Also, there is the prosaic reason: I have ill-defined features and naturally pale skin.” In the Guardian interview, he’d claimed that he wore black because it was slimming and meant he didn’t have to do laundry as often.

💀

Here, I’m going to answer:

Not what we meant.

Seems to be (see 1).

No.

Also no.

Possibly, depending on the rigor of your definition – It has its own dress, music, literature, customs, and achievements (see also Robert Smith’s devotion to Mary Poole, and The Cure’s induction this year into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame)

💀

When the early Cure catalog was re-released in 2004, including Pornography, Pitchfork said of it, “No matter how much the songs reek of crisis and desperation, the band seems as calm and on-point as a ballet troupe. That's precisely what makes Pornography-- which totally owns that other 40% of human moods—work. […] The record's most harrowing moment turns out to be a single: "The Hanging Garden", which is mostly just the relentless pounding of a single drum, with Simon Gallup's signature bass sound (the moves of a snake and the same scaly texture) rumbling beside it. If Smith wanted "unbearable," he should have hired a different singer, because his voice makes this-- and just about everything else-- completely thrilling.”

💀

Ninth grade, my last year in Junior High and the year of Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me’s release, I started wearing Converse and black sweaters with black leggings. But I wasn’t shooting for goth so much as whatever it was that Ally Sheedy’s Allison was supposed to be in The Breakfast Club. She’s called an “outcast” in press for the film, rather than goth. Hers was the look I wanted: dark, baggy, and comfortable. By high school, I was mostly what my friends called a “weekend waver,” meaning I dressed up for dancing in white-face/red-lips/black-eyes on Friday nights, but during the week I looked more or less normal. This was partly because my mom exerted a normalizing dress code (e.g., wouldn’t let me dye my hair purple until I was eighteen, no “scary” jewelry, etc.) and partly because I hate mornings and all that make-up and getting your hair to stand on end takes time I preferred to spend hitting snooze. During the week, I stuck to Doc Martens, old man blazers I found at thrift stores, and a slash of bright lipstick. I say more or less, because I also wore the hell out of a long purple cape I’d scavenged, and later a black motorcycle jacket—so it’s not like I could pass for one of the girls’ basketball team or anything. I still wanted to be comfortable. But at the clubs, dancing, I understood that I also had to be an object of a very particular kind of desire—so, out came lacy v-neck pirate shirts and crushed black velvet vests, belts slung low and pointy black, buckled shoes, black or black lace tights under holey jeans or stretch pencil skirts, sliver cross necklaces.

💀

"Late capitalism produces the desire for an aura that is felt to be prior to or beyond commodification, for a lived authenticity to be found in privileged forms of individual expression and collective identification. For as long as goth seems to answer that desire, it will thrive as an undead subculture: forging communities on the margins of cities, suburbs, campuses and cyberspace; defying constraints on gender and sexuality; and imbuing the stuff of everyday life with the allure of stylistic resistance." Goth: Undead Subculture ed., Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby, Duke University Press 2007

💀

In so far as the stuff I wore was usually mashed together from hand-me-downs, thrift store finds, and repurposed glam metal looks, it could have been called a stylistic resistance. There was no one-stop shopping à la Hot Topic when I was defining my look. I was resisting Keds and shaker sweaters with matching socks and beachy print longboard shorts under popped pastel collars.

And while I pinned my look together (often, literally), the “real goths” –the fans of cemeteries, vampires and Anton LaVey, slouched around in Christian Death shirts, trading Current 93 and Diamanda Galas tapes—or championed campier acts like The Cramps and The Damned. I could only hope to be passed a copied tape, having no access or knowledge of how to get access to those things. Those of us in the suburban wastelands were dancing to The Cure, Bauhaus, and Ministry on alt-night at the all-ages dance club, learning the words to Nick Cave and Siouxsie songs, blasting Joy Division or Killing Joke from our parents’ car stereos. I remember thinking I’d reached a new level of cool when I finally got passed my own dubbed copy of The Plague Mass. Then again when I found my leather jacket at a pawn shop. And even again, when I finally got to dye my hair a deep, dark purple.

I don’t have the tape Janet gave my any longer, or my copy of The Plague Mass, but I’ve kept this one. March 1, 1989: Janel Hell’s “Happy Death Ritual” show on KBVR.

💀

I've been thinking about how being even a part-time goth was a kind of protection for me in high school. I had terrible friends, but didn’t realize it. My home life was difficult in a way I didn’t yet have words for. I wanted desperately to make art of some kind that mattered to someone, but didn’t know how.

Those feelings of alienation and exceptionalism, coupled with a cultural awakening centered squarely amid white, lower-middle-class underachievers made me a perfect goth wannabe.

💀

The top search result video for “Hanging Garden” is not the original, but from an ostensibly live performance on a French music show. Except the band is not live, they are lip-syncing to the album version of the song, and Smith seems particularly pissed about it. He doesn’t even bother strumming his guitar for most of the song, and when he approximates the solo, it is with a listless gesture, like one might use to pet a taxidermied cat. He glares at the camera and side eyes Tolhurst while Gallup plays the bass with enough enthusiasm for all three of them.

On the French stage, Smith is wearing what looks like a Peptol-Bismol™ pink t-shirt. He’s also got red lipstick gashed across his lips and under his eyes. Goth royalty, sure, but I’d have died before I would have worn a pink shirt back then.

💀

The whimsical stuff and the pop sensibilities that Smith honed in the late 80s are exactly what I love about The Cure’s brand of goth, and it’s what probably outs me as not-really-all-that-goth. There is a certain type of fanatic who says that anything after Pornography isn’t goth, and that fans like me who love the pop stuff—KM,KM,KM and Disintegration, chiefly, and anything after especially, are all the proof they need of that. But I’m of the opinion that anyone who can’t laugh a little at themselves while dressed like Lestat or Pinhead probably can’t laugh at anything.

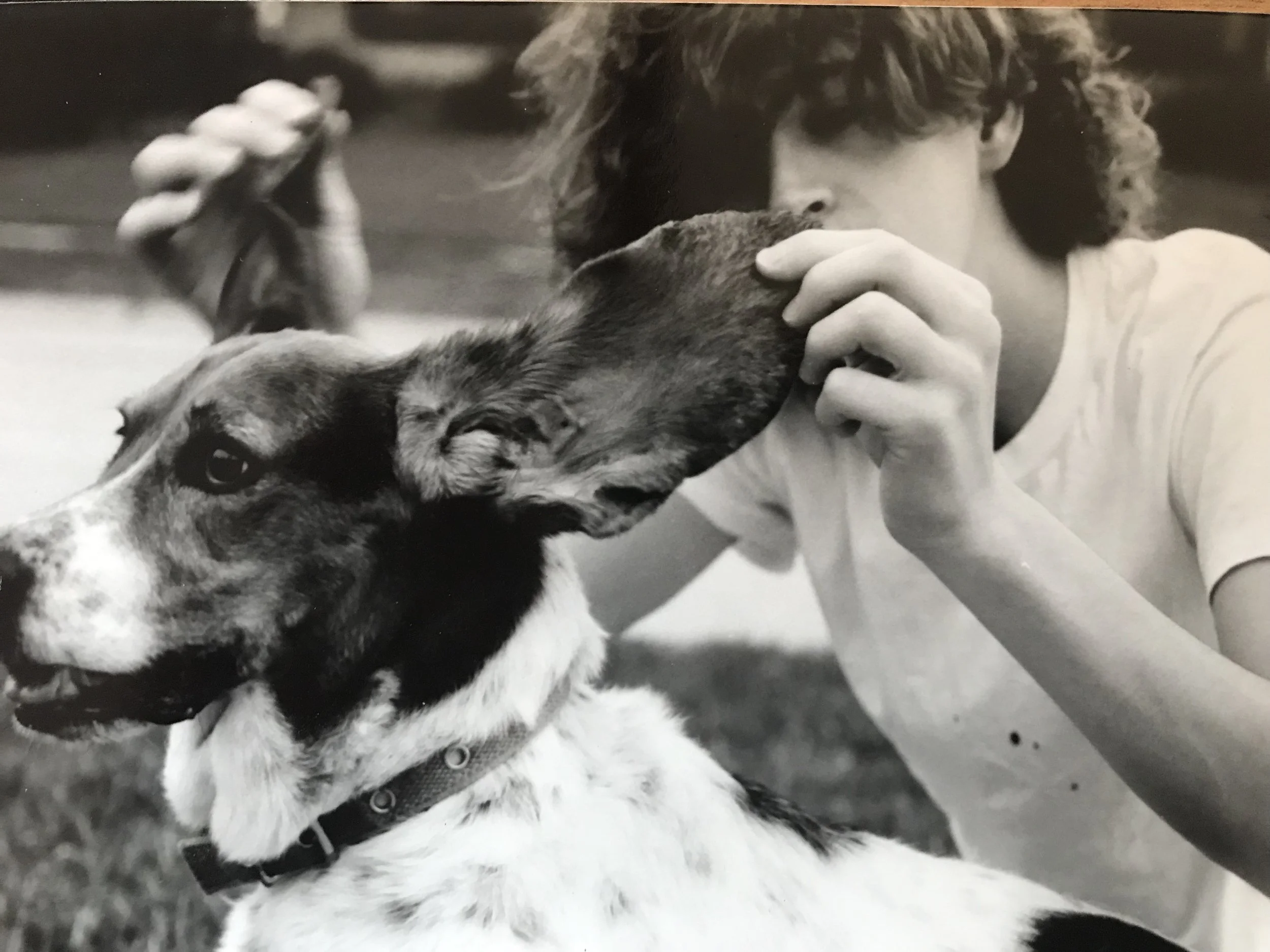

Smith could laugh at himself, even back then. One can see plenty of humor in the weirdness of the early videos, such as the giant armadillo that scuttles across the screen in “Hanging Garden,” the lurking polar bear in “Pictures of You,” Smith and Tolhurst tucking themselves into collapsing bunkbeds at the end of “Let’s Go To Bed,” and the entire video for “Close to Me,” (but especially Thompson’s comb-plucking).

💀

Best as I can tell, the answers to the above questions are:

Not since Wish | Disintegration | Pornography (depending on the approximate age of the respondent)

Definitely not.

Mostly. They are touring this year with two original members.

See 3.

Not since Seventeen Seconds | Boys Don’t Cry/Three Imaginary Boys (depending on the approximate age of the respondent)

💀

Just like regular pornography, we know goth when we see it.

💀

💀

Something I knew for sure to be true in high school: Goth is about a certain sensibility even more than it is about the music you listen to. While we can argue whether The Cure is quintessential goth, the fact is, millions of teenagers have drawn their black eyeliner to the sounds of Smith et al., and in doing so, claimed something vital for themselves that couldn’t be bought at a store or learned in school. And that’s pretty goth, after all.

* With gratitude and apologies to Elizabeth McCracken: https://lithub.com/elizabeth-mccracken-toward-a-unified-theory-of-the-doughnut/

Chelsea Biondolillo is the author of The Skinned Bird (KERNPUNKT Press, May 2019), and two prose chapbooks, Ologies and #Lovesong. She has a BFA in photography from Pacific NW College of Art, and an MFA in nonfiction and environmental studies from University of Wyoming. She lives outside Portland, Oregon.

IN HYSTERICS: DAVID TURKEL ON “RELEASE THE BATS”

I. “RELEASE THE BATS”

I was twelve the first time I ever consciously listened to Bob Dylan’s music. My best friend Rusty and I had gotten our hands on a copy of The Rolling Stone Record Guide and were gob smacked by the multiple runs of four- and five-star reviewed albums that littered his lengthy entry, some clusters as long as a typical band’s whole catalogue. We started our investigation at the top of one of these—the advent of his infamous “electric phase”—and dropped the needle on the a-side of our newly purchased copy of 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home. Then we laid back on top of the twin mattresses which occupied my room in Long Valley, New Jersey, prepared to be wowed. It was impossible to imagine what would emanate from those speakers that could take us further than Jimi Hendrix or Led Zepplin had thus far, but we were certain this was going to be it—true rock goddom. What we got instead, in jangles and honks, and the warbling hillbilly word salad which rode them, was a fit of some of the most hysterical laughter I can ever remember suffering, and it was a kind of suffering: our bodies ached, we could barely breathe; I vividly recall how challenging it was just to stand and reset the needle.

A couple of years later, a Stevie Ray Vaughn interview sent me to the record store to buy two albums of music from the nineteen thirties: Django Reinhardt and Robert Johnson. The Django was, and remains, jaw-dropping. I’d say that nothing could have prepared me for it, but truthfully something must have, as I instantly recognized it as virtuosic and essential. But the Robert Johnson was an altogether different thing—like Dylan, he had me rolling, clutching my guts. I can listen to him now and call his music soulful and haunting (or whatever), the way a connoisseur learns to qualify a sip of wine, but on that, the occasion of my first sip, all I knew was that I was drunk. Nothing I’d called blues to that point prepared me for his Delta-style guitar playing, and nowhere in me was there a space yet for the sound of that falsetto—the nakedest voice I’d ever heard. The place to hold these things was going to have to be freshly built, and I was beginning to realize that the sensation attendant to that process was, at least for me, nothing short of hysterical—breathless, full-bodied, almost a seizure.

I can tell you the road we were on and the name of the person driving the car I was in the back seat of when Eric Dolphy delivered his mighty gazelle punch to my sixteen-year-old brain. I felt like a character from Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights tryptic had suddenly come to life in the seat beside me and was trying to convert me to a new religion. And I can name the mile-marker we were crossing in Troy, Michigan, when the group of us almost came to our fiery conclusions in those first neuron-fritzing seconds after Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica was injected into the cassette player of Curt’s crayon orange Mustang. If a rattlesnake had been discovered on the floorboards of that car, we probably would have steered to safety with as much composure.

The first time we heard The Birthday Party was no different. Or, rather, it was entirely different. It was unlike anything we had ever heard before and we reacted the only way we could. Hysterically. We emptied a room in Jason’s mother’s house of all its breakables, turned off all the lights and re-cued Junkyard. Then we just started swinging furiously in that tight, dark space, until one of us screamed “STOP!!!” and the lights were turned back on to reveal who it was and how badly they’d been injured. This became a game we played as often as we could stand to, delighting in that first shock of illumination, most satisfied when blood was drawn.

And, in this, we were hardly unique. Famously, plugs were pulled on The Birthday Party’s first three shows in New York City during their American debut, by club owners convinced the group was trying to incite riots. It’s estimated they played less than twenty-five total minutes that week in September 1981, but it was more than enough for the fiercely uncompromising Lydia Lunch to be convinced she’d found her soulmates, and NME to alert audiences worldwide to the filthy five’s unparalleled fury (“cranking out of their guitar amps this murderous rattle, like the gaze of Medusa....”)

On European tours, where the Aussies were lauded as “Europe’s most violent band,” they learned to avoid extended engagements (or even, in some cases, to return to the same towns twice) as their shock factor served to hold the uninitiated in a sort of thrall, but repeat performances risked being interpreted as a dare by the most combustive in the crowds, for whom their music was nothing short of a license to tear shit apart. This was never their goal. Not really. On the heels of those first panic-inducing NYC gigs, writer Barney Hoskyns offered: “After the year of ‘Pop’, 1980—a miserable year spent trying to fit in with the new nonchalance – The Birthday Party realized the only solution was...TO ATTACK.” It’s a pithy, but misleading statement, as it suggests The Birthday Party were bent on attacking their audience, when in fact it was this “nonchalance” they held so contemptuously in their crosshairs. “Intensity,” said guitarist Rowland S. Howard, “is not necessarily violence. The way we presented ourselves to the audience was a direct challenge...to do something, to respond with some kind of intensity instead of just standing there and clapping politely and saying, ‘Oh yes, that was very nice.’”

Tapes of their performances support this more nuanced view.

One doesn’t see in The Birthday Party a gang of thugs looking to do combat with the crowd, so much as one feels in their presence the unmistakable sensation of having stumbled into a bad part of town, the sort of place where anything might happen. Mustached hustler Tracy Pew rolls on the floor, his Stetsoned head inside the bass drum, luridly humping the air like he’s trying to fuck the whole world with his bass guitar. The skeletal Howard, beneath an ever-present halo of smoke, stalks the shadowy outer edges of the stage, deftly wielding a guitar that has been described as everything from a razor to a fleet of Stukas. Frontman Nick Cave, the Imp of the Perverse, yowls and contorts beneath the stoic gaze of multi-instrumentalist, Mick Harvey—the hard carny who’s brought his freak to town. All the while Phil Calvert’s drums crack, like shotgun shells exploding inside a burning police car.

It’s aggressive music to be sure, but rather than hostile, I would argue the music of The Birthday Party is oddly welcoming. It presents an invitation: to recast yourself in its image, become the thing that scares you. “I try to excite people and confuse their normal way of thinking, if they react aggressively to that, so be it,” said Cave in an interview in ‘82, adding: “I think the audience has as much right to perform as the band.”

Our impromptu cage matches were in their own small way testament to this. All we knew was that a different response was demanded of us by this music. It pressed us to connect with something primordial, preverbal—to “release the bats” as it were, the ones that lived inside, in hidden, unexplored spaces suddenly illuminated by the shiny, dark object (the black star) of their sound.

By that time, I’d seen “goth” superstars The Cure in concert (my first date, Flock of Seagulls opened...) and it would never have occurred to me to compare The Birthday Party to them, nor to any other band in the genre, though the label clings to them more stubbornly than a shibari knot. Live, The Cure seemed most intent on sounding like their records, as if what we were after was the communal experience of listening to a cassette tape while watching the shadow puppet of Robert Smith’s hair bop around on the scrim, like a lonely porcupine looking for a mate. Truthfully, it would be easier to compare their “performance” to a Bob Ross video, for the comfortable ease with which it demonstrated the reproduction of a familiar reality, than to the ego-shattering spontaneity The Birthday Party both embodied and inspired. This is because the essence of goth as a musical genre is, at heart, composure—not an energy or emotional state at all, so much as the codification of these.

Goth is distant and distancing; The Birthday Party, immediate and visceral. Goth is lush and bloodless, like a Versace ad; The Birthday Party is music’s equivalent of a prison shiv. Goth aspires to the majestic—its hollow, delicate vocals and spindly, reed-thin guitars hover over a reverb-drenched dissonance, like some nocturnal bird of prey swooping above a chaotic landscape. There’s pain and misery down below, to be sure, fires dot the horizon, but goth floats; it is inured; its private shame and pain, it seems to say, has pushed the world into the margins. The Birthday Party, by contrast, are boots-on-the-ground hooligans, smashing windows, heaving Molotov cocktails, and if you listen close you’ll hear another sound, one which more than any other separates theirs from anything in the genre knows as goth: laughter. The Birthday Party heave with it; goth holds its breath.

For me, The Birthday Party can be placed on one list, and one list only: that of incomparable things. It’s as antithetical to see them counted among a cohort of aesthetically- linked bands, as it is unimaginable to consider arguing for their preeminent position there. Were I clever enough, I’d construct a metaphor comparing lists to mirrors and The Birthday Party to vampires for their inability to be captured by them. Certainly, nothing sounded like The Birthday Party beforehand, and those few worthy imitators since—Green River, The Chrome Cranks, The Jesus Lizard—(all equally “un-goth”) are probably more aptly compared to Australian swamp-rockers, The Scientists—they, at least, were a band. The Birthday Party, I contend, were no such thing. The Birthday Party were a monster.

Which is all to say that, while I don’t consider The Birthday Party goth in the slightest, I do think they’re vlad as hell.

II. “IN THE AIR TONIGHT”

According to Wikipedia...

...at some point rock-and-roll died (who the fuck knows, maybe even when goofy songsmith Don McLean said it did...) and then Iggy Pop, this demented voodoo priest, cast a spell of darkest magic calling forth the corpse from out its grave, and there came The Birthday Party, stinking and oozing, caked in a coffin’s worth of native soil, crashing their dark ship into England’s rocky coast.

“I just sang,” said Genesis drummer, Phil Collins, “I opened my mouth and they came out.”

The words, he means, not The Birthday Party, the words to his song, “In the Air Tonight,” recorded, the year of their landing, in the “Stone Room” of London’s Townhouse Studios. It would become the advance single of his first solo effort, Face Value, released February 1981, and hold a position on the UK singles charts for over thirty-one weeks, and I can’t help but cue it now, as I imagine a midnight in Spring of that year, as five dark figures cut between the shadows of the White City to converge on that very same Stone Room.

When producer Nick Launey meets The Birthday Party there, he’ll note their uniformly black attire and ruinous air—like a decayed, rat-infested church—and be left with the titillating impression that he’s just recorded the music of actual vampires. Launey’s been commissioned for a Peel Session by the band’s 4AD label, and he’s managed to secure rock-bottom rates booking an after-hours slot from studio two’s daytime resident—none other than Phil Collins, who, apparently, can’t leave the room now, the stone having claimed him...

In all Townhouse lore no song looms quite so large as Collin’s masterpiece. Probably because his signature drum tone so perfectly conjures the image of the room’s much-heralded building material (though it’s hard to know how all the stone in the world could interfere with that amount of gated reverb). For their part, The Birthday Party will have absolutely no use for it, choosing instead to lug in sheets of corrugated steel, transforming the warm, natural cave- like resonance of the space into an unforgiving crash-pad. They’ve been fucked by the studio routine in the past, cowed into prescribed behaviors which ended up capturing little more than cartoon sketches of their glorious noise, and they’re done with all that. Their last full-length album, Prayers on Fire, possessed a few triumphant flashes—most notably “King Ink” and “Nick the Stripper”—where the Monster they’d only successfully summoned before in live performance, could be glimpsed in the playback reel, and they feel they know how to do it now, how to draw him out into these cold, empty spaces, hold him there for good (or ill). With the two singles recorded over this April witching hour session—“Release the Bats” and “Blast Off!”—he will fully incarnate, once and for all, never to leave them; perhaps even consuming them. Summoned, in a sense, by laughter.

For “Release the Bats” was, it must be said, first and foremost, a joke.

“It was done tongue-in-cheek,” notes Mick Harvey, “this kinda ridiculous thundery rockabilly thing. The first time we got from beginning to end in the rehearsal room, everyone completely packed up laughing...”

When I tell you The Birthday Party were not a band, I mean that theirs was a conspiracy to supplant notions of musicality with visceral experience. One doesn’t measure the bass parts of Tracey Pew, for instance, in notes, but in thickness, in shades of black, in sticky, murky, slobbering heaviness; in the distinct sensation that you’re hearing not just a primal noise but a pornographic one. He holds the songs together, don’t get me wrong, but not like a metronome. More the way a tarpit could be said to have held things together. Similarly, Rowland S. Howard didn’t play songs; he vandalized them—slashing through verses like a drug fiend looking for a stash in the couch cushions. As for drums, the thing Phil Calvert could never fully wrap his head around (the reason they would sack him just over a year after the release of this recording and move Mick Harvey behind the kit), is that The Birthday Party didn’t require a drummer—what they were in need of was a demolitions expert. It’s Nick Cave you hear on the recording of “Release the Bats,” battering the snare out-of-time, as Calvert complained (signing his own death warrant in the process) that it was impossible for a “schooled musician” to play off-tempo.

In all these ways they were perhaps closer to performance artists than musicians; even, in and off themselves, a work of sonic sculpture. But when I call The Birthday Party “a monster,” I mean to say that they traveled this essentially intellectual road to an intensely primal place. In ways most reminiscent of George Bataille, perhaps, they recognized in horror, pornography and a wickedly provocative, signal-jamming humor, mechanisms which leapfrog past the rational, directly into the sludge—the places where, in each of us, desire first emerges, unadorned of the bells-and-whistles of selfdom. The Dim Locator, Howard reckoned himself, by which he meant, I’m not stupid, but I know how to get there....

“Early on,” he reflects, “we were all big fans of Bowie, Roxy Music, Alice Cooper and Alex Harvey who were all entertainers but we wanted to take it a step further, we didn’t want to take off our makeup when we got home, we wanted to be the same on stage as we were on the street.” Which is to say that the laughter of The Birthday Party doesn’t risk dropping the performative mask precisely because they’re not wearing one. It’s more akin to the laughter of Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch—the sound of unbidden self-possession, of those who know their element and revel in it. The phony monster, after all, is the one trying to scare you. The true monster’s simply doing the thing it loves best. In this sense, The Birthday Party is that thing goth dresses up as. It’s been said that when they threatened to interrupt a Bauhaus performance it wasn’t with physical violence, but rather a promise to pants lead-singer Peter Murphy (Pew ended up drawing a penis on Murphy’s chest instead). For the Monster innately understood that, while goth with could suffer a beating, pantsless—stripped of its costume, that is—it could not stand.

A year after the release (and shocking success!) of “Release the Bats,” so-called “goths” would flock London’s newly opened Batcave nightclub, slowly cultivating the overly precious and pretentious air which eventually overwhelmed the last vestiges of punk, transforming the entire scene into little more than a pop parody, where the notion of The Birthday Party was only as meaningful as a true vampire might be to a Halloween trick-or-treater—a snapshot for the makeup mirror. No matter. They were gone by then; escaping, first to Berlin, then the grave (“black puppet go to sleep, mama won’t scold you anymore...”)

But I want to lift the needle here. Reset it back a few grooves, back to the Stone Room, and the midnight chimes dividing Phil Collin’s time there from that of the Monster’s: the space between morning and night, dark and shiny, between “Release the Bats,” and “In the Air Tonight.”

Hold this space in your mind like a coin, if you will, spinning end over end. I offer it to our conversation, in part, because I feel that goth lives somewhere between these two songs. In greater measure, because I’m not sure goth actually lives at all, but perhaps only occupies the thinnest space between two clearly present states: pop & art.

Consider Collins’ song. Reverb-drenched, feedback-tinged, death-haunted. Unexpectedly propulsive and asymmetrical. As its resurgent fame as the centerpiece of 1984’s Miami Vice’s pilot attests, no song more effortlessly conjures an urban nightscape suffused with dark intentions and imminent danger than this. And so the question that must be asked here is simply: how is this not a goth tune?

Clearly Stuart Orme, director of its Grammy-nominated video, doesn’t know. The setting he chose might just as easily have served as Jonathon Harker’s Transylvania lodgings—a bare, clapboard room, complete with sickle moon and its very own phantom window-creature. At one point, Phil, the seated figure occupying the room’s sole wooden chair, subdivides—a second, spectral-self rising from the corporeal one to take its place at the window. Later, in a hall of doors, he apparently stumbles upon himself confronting himself as the phantom window-creature—I really can’t be sure, I’ve watched it over and over, phantom-Phil’s image wavers as if under water—suggestive of the drowning hinted at in the song, perhaps?—then seems to disintegrate; light explodes from the doorway with all the fury of a terrible insight. All within yet another Phil, this the grand narrative of his looming, shadow-sculpted face. The only thing not goth about it, frankly, is the bald spot on the back of Phil’s head as he enters the hall of doors.

But this, truthfully, can’t be taken lightly, the bald spot. It’s the shiny side of the coin we’ve just flipped, after all. The key to everything, I imagine. Consider, for instance, a Phil in Robert Smith’s mascara and fright-wig tresses delivering this song. Could you feel that coming in the air tonight? Position him there in lipstick and clown-white, as the face of the album cover. Or suit Smith, if you prefer, in Sussudio threads and cue “Close to Me.” Oh Lord! Is it possible that goth is just a costume drama for people ashamed to admit that they like pop music? Is this all really just the story of hair?

Phil’s is going. So be it. He wears jeans and a flannel in one video, a rumpled suit in the next. He’s just a guy, is what the bald spot says—the everyman. He feels something out there and he wants to know if you feel it, too. He’s haunted by difficult memories and now he senses more trouble in the offing. He sings to a dark figure, someone he’s seen do a terrible thing, but he’s not threatening, so much as withdrawing (“I would not lend a hand”), still he feels there’s no escape; the thing approaches, and he’s bracing himself, and you can sense his fear mingling with the resolution to meet it squarely when, at last, it arrives.

It’s The Birthday Party, of course, who alone deliver on goth’s promise: not to face the night, but to become it— "...what music they make!”

David Turkel is a playwright, screenwriter and poet based in Corvallis, Oregon. His play Clytemnestr@pocalypse premiered at the Théâtre National de Nice, France, March 2017. His newest work (ha)—a cabaret performance featuring Eva Braun in Purgatory, debuts in 2020 with The Little Green Pig Theatrical Concern (Durham, NC); excerpts published in Opossum, Fall 2018.