first round

(9) M|A|R|R|S, “Pump Up the Volume”

turned down

(8) Scritti Politti, “Perfect Way”

242-196

and will play on in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/8/23.

To Make a Certain a Maybe: Martin Seay on “Perfect Way”

I) One Hit

The 1980s are the defining decade for one-hit wonders. Although the term predates the era—the earliest appearance I found is in a Billboard from 1972—the ’80s are when the concept really starts to emerge as a category and pass into common parlance. It’s worth thinking about why.

The pop charts of the ’80s, we should note, aren’t any more thickly populated with one-hit wonders than those of other decades. In an analysis for Towards Data Science, Todd Kerpelman figures that the ’80s actually had the fewest one-hit wonders of any decade from the 1960s through the aughts.

That surprised me; it probably shouldn’t have. When something’s ubiquitous we tend not to register it as a phenomenon, and therefore don’t need a name for it. In the days prior to the album era, the domain of pop music belonged as much to radio comedians singing novelty tunes and random teenage doo-wop groups as it did to big acts like Nat King Cole, Patti Page, and Elvis Presley; there wasn’t much expectation that somebody who had a hit would ever have another one. In the late ’60s and early ’70s the situation didn’t actually change much—the charts were just as full of goofy jokes, unctuous earworms, and flashy dead ends as they’d ever been—but by then popular music had come to occupy a different place in the culture: a discerning bohemian contingent had adopted it as an interest, and its attention was directed away from chart hits, toward music meant to be absorbed over the full length of an LP. By the end of the ’70s the spotlight had shifted again: albums had gotten bloated and boring, and the energy and good ideas were to be found in seven- and ten- and twelve-inch singles recorded by reggae and punk and disco and new wave acts that often didn’t exist long enough to cut follow-ups. But the album-era assumption that good records are mostly made by a few heroic geniuses persisted, generating a dismissive and/or apologetic vocabulary for talking about other noteworthy music. I think our understanding of “one-hit wonders” as such is probably an artifact of that.

And let’s face it, it’s an interesting way to categorize songs. Unlike the formal distinctions we use to sort, say, cowpunk from coldwave from cumbia, the characteristics that define the hits of one-hit wonders aren’t located in the music, or in the artists’ apparent aims; I mean, it’s hard to imagine somebody going into the studio thinking, “Today I’m going to make my only hit.” Instead, these songs achieve their defining status after they’re written, performed, recorded, and released, based not on what they are but on what other people do with them. One-hit wonders are made by record labels, and broadcast media, and viral moments, and ultimately by audiences, not by artists. It’s not like these songs share common attributes, or constitute their own genre.

Except maybe they kind of do?

II) Pas de Hors-Texte

Okay, bear with me here for a minute.

1967, the year that arguably inaugurates the album era, also saw the publication of three books that launched the career of French philosopher Jacques Derrida. In one of these, Of Grammatology, we find the (in)famous epigram “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte,” by far Derrida’s most-quoted statement. People who know only one thing about him probably know some version of this sentence. With respect to the general reading public, it might plausibly be called his one hit.

In her 1976 translation, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak wisely hedges her bets and gives us two English versions, of which “There is nothing outside of the text” is the better-known and “There is no outside-text” is the more literal. With Derrida, the fact that a sentence can be taken as saying multiple not-quite-identical things is to be understood more as a feature than a bug. Although Spivak doesn’t mention it, we might also note that hors-texte has an idiomatic meaning in French-language publishing: it refers to material, usually illustrations on glossy paper, printed separately from and then bound together with the standard pages of a book. (In English we call such material “tipped in.”)

“Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” appears amid a consideration of the work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, during which Derrida identifies, inverts, and destabilizes—which is to say, deconstructs—Rousseau’s notion that writing is an unnatural supplement to speech. Derrida’s point, more or less, is that “the text” isn’t limited to Rousseau’s printed words, or even to printed words in general, but includes the whole sprawling system of signs, signifiers, tropes, categories, distinctions, and differences by which we make sense of the world. Whenever we need to figure the significance of something, we look at it through whatever interpretive lenses are already at our disposal: the Bible, astrology, our therapist’s advice, #inspo, our sommelier training, something we saw on Queer Eye, something a coach yelled at us in middle school, The Communist Manifesto, Atlas Shrugged, Of Grammatology, and so forth. We don’t always realize we’re doing this; we tend to think we’re empirically assessing our lived experience of reality when we’re mostly just comparing it to stuff we already know. We’re also probably crediting our already-known stuff with a stronger claim on transcendent meaning, a claim that qualifies it to serve as a lens. At the very least, we figure that our lens is sufficiently removed from the experience that we’re currently having for it to be valid as a benchmark—not unlike the way that, say, a glossy page of photos stitched into a book might suggest factual verification of what the text describes. That, Derrida suggests, ain’t necessarily so: these distinctions and hierarchies are never as stable as we imagine, and we’re always already entangled in any new experience we might hope to objectively analyze. Il n’y a pas de hors-texte.

Okay, back to one-hit wonders. If we limit our assessment of this group of songs to their intrinsic qualities, they’re all pretty different—but we don’t do that. Music is made for an audience; that audience has always already heard other music, and its experience is always mediated by its prior knowledge. To a great extent, that’s how music works: by activating that knowledge. We hear a sound, we recognize it as an accordion, we listen to the chords and rhythm to anticipate the music’s form or genre—norteño? zydeco? tango? champagne music?—and then we assess it in that context. This contextualizing process is a huge part of our aesthetic experience.

That’s especially the case when the context includes other work by the same artist. “Revolution 9” hits different if we know the Beatles by way of “Please Please Me.” For those who’ve been keeping up with Beyoncé since “With Me,” “Hold Up” unfolds a more detailed map of her journey as a singer and songwriter. And of course these and other artists deliberately cultivate their personae by anticipating familiarity with their work and using it to their advantage; fans of Taylor Swift’s Red-era demolitions-à-clef of caddish exes, for instance, may register her recent declaration “I’m the problem, it’s me” as a momentous shift.

So. What I think we hear in the hits of one-hit wonders—the common quality that links our experience of them—is a discontinuity in our usual contextualizing process. A gap. A swerve. A little hiccup.

Because, first of all, these songs were all hits, right? As such, we tend to encounter them in public or semi-public settings, less often by choice than by accident: jabbing a car-radio search button, wandering the aisles at a grocery store. We’re aware that we’re sharing the song with others with whom we have little else in common; beyond that, our individual experience of them takes one of two paths, as determined by our prior knowledge.

If we know anything about the artist who recorded the song, then we tend to experience their one hit as a peculiar intrusion into the Top 40 from a different cultural realm. If you’ve spent years studying live versions of “Dark Star,” or if you know Laughing Stock as a foundational post-rock album, then hearing “Touch of Grey” or “It’s My Life” at the gas station is always kind of weird. If your late-’80s Friday nights were occupied by episodes of Miami Vice, then hearing its theme song—or, for that matter, its top-billed star—on the radio is always a little funny. In these cases the defining discontinuity comes from the fact that you and a bunch of strangers are all listening to the same song, but thanks to gaps in context you’re not all hearing the same song.

If we don’t know anything about the artist who recorded it—or if it’s one of the rare instances in which there’s just not that much to know—then our experience is defined precisely by the absence of context. We recognize it, we compare it to other music, we might even place it in a genre or be reminded of times when or places where we’ve heard it before, but we find no answers to basic questions like Who made this? Where did it come from? Like a glowing atom of ionized neon, the song floats unattached to such associations, thrilling and faintly eerie in its purity.

Which brings me at last to Scritti Politti. Is “Perfect Way” the greatest song by a one-hit wonder of the 1980s? Hell, I dunno; I think it’s pretty good. If we ask a slightly different question, however—is Scritti Politti the greatest one-hit wonder of the 1980s?—then the answer is clearly yes, hands down, let me know who comes in second.

Here’s why. If you don’t know anything about Scritti Politti, then “Perfect Way” is a completely successful pop song: as melodically portable as a Rodgers and Hart tune, as immaculately arranged as a Motown classic. It emerges fully-formed into cultural consciousness, bursting into our heads like Minerva in reverse. Bearing-ball flawless, it requires no augmentation, no interpretive intervention to feel complete.

If you do know something about Scritti Politti, then the song’s apparently smooth surface discloses seams that widen into fissures, some of which are deep indeed. If you buy my idea that our experience of these songs is defined by gaps in context—distances between what we need to know and what there is to know—then “Perfect Way” puts us in Evel-Knievel-at-Snake-River-Canyon territory: the span is wider than you might expect, and the crossing might get a little bumpy.

That whole bit up there about Derrida was not entirely gratuitous, I’m afraid.

III) “Perfect Way”

Let’s say you’re at a pharmacy—browsing for random crap to put in your basket along with the one embarrassing personal item that you actually need—when the song comes over the PA system.

Maybe it’s the ka-CHANG that catches your attention: a quick down- and ringing upstroke on an electric guitar, thin and clean. The guitar’s fighting for space among three other instrumental voices: a steady pulse of synthesized strings, a syncopated riff of percussive plunking, and a brassy, impatient two-chord stab that answers the guitar’s question. The keyboard parts, precise and urgent, push the song forward; the guitar, a little out of control as guitars tend to be, drags it back. Ten seconds in and there’s already tension, already a lot going on.

And it’s not even the real beginning, just a teaser. A big collage of sampled toms and hi-hats clears the field, and the song drops into lower gear, drums and a rubbery synth bassline interlocking with a crisp guitar lick and a whole supporting cast of keyboard tones. The effect is a little like watching somebody juggle a dozen random objects pulled from kitchen cabinets: somehow it all stays aloft, avoiding collisions by a hair’s breadth. First verse.

The singer comes in, a cottonwood-seed falsetto, airy and soft. “I took a backseat, a backhander, I took her back to her room, I better get back to the basics for you.” The descending aw yeah that follows is one of the all-time great pop adlibs, introducing a gentle melancholy, blazing a reassuring harmonic trail toward what’s about to be a whole bunch of chords.

The rest of the verse is a little hard to parse while you’re perusing travel-sized toiletries, but the jazzy, corkscrewing section that comes next—“Apart from everyone, away from your love, a part of me belongs apart from all of the hurt above”—draws you in again, mostly by threatening to swerve into a ditch. Whoa, you think, this is the chorus? This is the chorus?

It's not the chorus. The chorus—you heard it earlier; it was also the intro—arrives riding a punchy drum fill, pulsing synth strings now supplanted by the first notes of the big hook: “I… got… a… perfect way…” The lyrics that follow are crowded into space that seems too small for them, carried down and back up to the hook on a halfpipe of melody. Even though (or because?) you’re missing some of the words, it’s probably this chorus that gets stuck in your head later, prompting you to find the song again.

Scritti Politti, huh? Annoying name, but somehow right for what they’re doing, though it’s hard to say why, or why.

Maybe you find it on YouTube, in which case there’s the video: mostly black-and-white, though often tinted, like silent films used to be. Lots of panning and tracking, quick cuts, cryptic closeups. Shots of the band—three preppy young white guys, singer and keyboardist and drummer, mostly goofing around in a recording studio—intercut with a succession of ethnically diverse, feminine-presenting models. (You might recognize one of them as supermodel-to-be Veronica Webb.) There are lots of marks: letters, numbers, roadway stripes. By extension, there are also lots of surfaces: paper, glass, pavement, even the filmstock itself. There’s a book which, if you are pathologically motivated to do so, you can identify as the 1979 story collection At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid. There’s some running, some hair-tossing, some sheepish dancing. It seems like they’re maybe in Paris? The models and the guys in the band never appear in the same frame—except, you might notice, for one rule-proving exception at 2:38—and this separation circumvents any overt portrayal of the seductive prowess that the song’s narrator keeps claiming, while introducing a different tension, a sense of things not happening.

After a couple of plays, you’re noticing other layers: the way tambourine and cowbell scuff up shiny keyboard lines, the way the tauntingly monophonic piano solo recaps the guitar lick from earlier verses. You’re also catching more lyrics. You registered a couple of puns on your first listen—“got a way with the word” or “got away with the word”?; “don’t have a purpose or mission” or “don’t have a purpose, omission”?—but once you start looking for word-games, you find a lot of them.

What’s weird is that while the song seems straightforward at first—the playful complaint of a temporarily frustrated lover—the closer you look, the harder it is to pin down what it’s saying. The first lines, for instance, double back on themselves even as the music rushes onward. In them, the narrator seems to bemoan his lover’s indifference (“I took a backseat”) and maybe her abuse (a backhanded blow), but there are other interpretations at the margins. Automobile backseats are, after all, archetypally sites of impromptu sexual adventures; in British English a backhander can also mean an illicit, off-the-books reward. And sure enough, there’s the narrator taking “her back to her room,” so apparently things aren’t going too badly for him? (Then again, is the “her” also the “you” he’s addressing in the rest of the song, or somebody else? If the former, why the shift? If the latter, who?)

What’s happening here, of course, is less a coherent narrative than a riff on “back” idioms, specifically those with multiple connotations, more specifically those with opposing connotations. As you try to figure out what’s going on—just as the band knows you will—the lyrics steer an ambiguous path between inert clarity and indecipherable chaos. And the ambiguity is the point.

There’s plenty more where that came from. “A part” and “apart,” homophonous, mean approximately opposite things. A “proposition” can be a philosophical assertion, or a sexual advance, or both. Does the song’s addressee actually have “a conscience” and “compassion,” or are these just words that she has a way with, or got away with using? If “complacency” refers to an absence of desire, what does it mean to have a “heart full of” it? Is the narrator suggesting that the addressee emulate his behavior—the usual sense of “take a page out of my book”—or has his pursuit of her caused him to abandon some of his self-imposed rules? How does one go about forgetting how to remember?

The narrator keeps insisting that he’s got “a perfect way,” but he never says what it is, exactly. He doesn’t because he can’t; the perfection of the way consists precisely of its imperviousness to explanation, to having its meaning fixed. Instead of telling, he shows. The key detail is that it’s not a way to make a no a yes, but rather “to make a certain a maybe.” The narrator isn’t trying to persuade the object of his desire to do anything, or believe anything; quite the opposite. His approach instead promotes radical doubt, a vibrant disorientation within which, rather than nothing meaning anything, everything means at least a couple of irreconcilable somethings—a mentally stressful condition that psychologists might call cognitive dissonance. (The narrator also doesn’t lay claim to a perfect way to make the girls go wild, or go gaga, or whatever, but rather to make them “go crazy.”)

This all might come off as vile pickup-artist gamesmanship but for the sense that the narrator is subject to and speaking from within the same radical doubt that his rhetoric evokes and creates. (The demasculinized gentleness of the singer’s delivery also helps diminish the creep factor.) “Perfect Way” ends up being less a song about desire than a song about being about desire—about how the objects of desire don’t maintain absolute positions when you try to understand and pursue them, about how it’s impossible to know the mind of the lover, or for that matter your own mind. The way is perfect not because it empowers the narrator to get what he wants, but because it doesn’t. Instead, it suspends him and his beloved and his desire in an elastic web of signification.

If you got this far down the interpretive slide, maybe you’ll entertain the thought that this tension between desire and doubt is paralleled by the first thing you noticed about the arrangement: the forward drive of the keyboard riffs dragged back by the messy ka-CHANG of the guitar. Maybe you’ll think about how the song’s ambiguity—the way its lyrics dance around each other while evading decisive interpretation—sort of reflects the way music works in general: pitches and rhythms don’t have any intrinsic meaning, but only function through their difference from other pitches and rhythms. And, shit, come to think of it, it’s basically the same deal with language in general: words don’t have any stable connection to underlying reality, but only accrue meaning via incremental connotative differences from other words. They are, in at least two senses, empty by definition.

Yet even as the band makes its point, it tips its hand. In what seems like an appropriate paradox, the lyric that insists most explicitly on the free-floating arbitrariness of language—“I’m empty by definition”—also gestures outside the song. It is, you might realize, a citation: a reference to the “empty signifier” that features in the works of poststructuralist theorists.

There’s an even clearer citation in the line that follows, maybe the best line in the song, the one that best demonstrates how it all works: “I got a lack, girl, that you’d love to be.” That twist at the end—she wouldn’t fill the lack, she’d be the lack—lands as clever, but then keeps feeding back. If the narrator already has the lack that she’d love to be, then she won’t really be the lack, will she? The lack, already present, will just shift onto her; she’ll embody it and signify it, and from the narrator’s standpoint it will supersede all other aspects of her identity.

But “lack”—showing up here hot on the heels of “empty by definition”—is also a big poststructuralist concept, particularly for Jacques Lacan, who uses the term to refer to the unspecifiable origin of desire, most fundamentally desire for an imagined wholeness, a desire that arises just from being deposited into conscious existence. Derrida, too, writes of an originary lack—“an always already absent present” as Spivak puts it—at the heart of the experience of being in the world. The narrator’s experience of this fundamental lack will become entangled with his desire for the song’s addressee such that each has meaning only via reference to the other, and otherwise cannot really be perceived at all. Fun stuff, Scritti Politti!

So who the hell are these guys, anyway?

IV) Scritti Politti

If I were to tell you that the debut single by Scritti Politti—the band that would later have a U.S. Top 40 hit with “Perfect Way”—came out in 1978 and was called “Skank Bloc Bologna,” you might (just as I did) hazard a guess or two as to what it would sound like based on that information, and those guesses would almost certainly (just as mine were) be wrong.

Listening to this, I’m struck by a couple of things. First, it’s right in line with other postpunk music coming out of the UK at that time, from Wire to the Raincoats to A Certain Ratio: reggaeish basslines, detuned guitar, cryptic menace, the whole deal. Second, it’s honestly kind of good, striking an effective balance between venom and tunefulness; the singer has a lot of, y’know, ideas about stuff, but they’re delivered through solid songcraft, with catchy repetitions and lyrics that sit firmly on the melody.

And yes, that is the same voice in 1978 that we hear in 1985: singer, guitarist, and principal songwriter Green Gartside, Scritti Politti’s only constant member. As probably befits an artist who has consistently questioned the degree to which language can ever lay claim to authenticity, Green Gartside is not the name he entered the world with. Born Paul Strohmeyer in Cardiff in 1955, he spent his early childhood all over South Wales, relocating as his packet-soup-salesman father’s job required. His dad died; his mom got remarried to her boss, a Newport-based solicitor named Gordon Gartside. Young Paul started calling himself Green mostly because there were too many other Pauls in his class, and because in the late ’60s kids were doing stuff like that.

South Wales was provincial and conservative; Gartside has said that pop music, especially the Beatles’ music, was “the only thing that made my life bearable.” (There are, by the way, a ton of great interviews of Gartside; I’m mainly drawing on a 2014 conversation with Kodwo Eshun at Goldsmiths, University of London, one of a series of lectures and discussions later compiled as the book Post-Punk Then and Now. Unless otherwise noted, my Gartside quotes are from this conversation.) Just as they did for many other young people who did not later land a song in the US Top 40, the Beatles reached Gartside as an annunciation from a much richer world, encouraging his appetite for new music and new ideas, the more challenging the better.

New ideas arrived in the person of Niall (sometimes Nial) Jinks, an English transplant from Gravesend in Kent who at age fifteen or so was already an avowed Marxist; he and Gartside formed a chapter of the Young Communist League at their grammar school. (There were, one hopes, Red Gartside jokes.) Gartside adopted Jinks’ fondness for folk music—always compatible with proletarian values—and also discovered new favorites like the Incredible String Band and Captain Beefheart and the Faces and Matching Mole, the latter two of which he speaks of traveling to the 1972 Reading Festival to see, attired in a pair of loon pants and one of his grandmother’s dresses.

Gartside and Jinks ended up in art school at Leeds Polytechnic, ready to be immersed in an atmosphere of intellectual inquiry and debate about the long-past-due restructuring of the world. This didn’t happen—or, as Gartside tells it, it happened in spite of the university, not because of it. Gartside already had an interest in conceptual art from a course he’d taken in Newport (and quite possibly from Yoko Ono by way of the Beatles) and he’d hoped to refine it further in Leeds, but the Polytechnic faculty didn’t get it, didn’t like it, and couldn’t be bothered. “It was just art lecturers staggering in hungover, and suggesting various female art students go for a Chinese meal with them,” Gartside recalls. “The whole place was dreadful. So, something had to be done.”

Gartside co-wrote a polemic decrying the repressiveness of art schools; he also programmed his own alternative curriculum by inviting members of the Art & Language group to give talks in pubs. When the university tried to bounce him out of his student studio with the accusation that he was spending all his time writing abstruse theoretical texts instead of making art, Gartside just started hanging his texts on the walls. This presented the faculty with a predicament when the time finally came to evaluate his degree exhibition, in that none of them could make heads or tails of it; they borrowed art historian T.J. Clark—a former member of Marxist provocateur groups like King Mob and the Situationist International—from the nearby University of Leeds to confirm that Gartside wasn’t just spouting nonsense. Clark gave the all-clear.

Under communism, or so the theory goes, art and music and other creative pursuits would (will!) be de-professionalized and de-commodified, with everyone so inclined freely able to make and enjoy them. While Gartside had played in a few bands by that point, music had been ancillary to his main pursuit of art + theory + revolution. This all changed on December 6, 1976, when the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy Tour kicked off right there at the Polytechnic, mere days after they’d called a TV presenter a “dirty fucker” during a live telecast, an event that qualified as a national crisis, or an absurd sideshow, or both. Gartside walked out of that concert with the convulsive realization that he not only could, but should, and maybe had to reconvene his musician mates and start booking gigs. The Pistols had revealed a massive gap in the seemingly unassailable aesthetic battlements of the ruling class, a gap that daring rock bands could slip through to seize the media bullhorn and initiate the total destruction of the smug, pietistic bourgeois ideology that had repressed British culture pretty much since VE Day. If this outcome didn’t quite seem inevitable, it seemed entirely achievable.

Some version of Gartside’s assessment was widely shared among UK postpunk and new wave acts, an improbably large percentage of which formed after their founders saw the Pistols play; within Leeds alone, Gang of Four and the Mekons and Delta 5 all emerged at around the same time, along with many other less storied projects.

But Gartside and his band—Jinks on bass, fellow Polytechnic student Keith Morley (credited as Tom Morley or Tom Soviet) on drums—didn’t stick around after graduation, instead relocating to Camden Town in London, an enduring nexus of counterculture activity. In Leeds “for about three weeks,” Gartside told Eshun, they’d called themselves the Against, “which really is an appalling punk name.” Things were happening fast; less than a year after the Anarchy Tour, punk was over so far as Gartside and his peers were concerned: co-opted, cartoonish. It was time for ideas, for rigor, for questioning assumptions, for the next thing.

Gartside had a sense that the Italians were on the right track, particularly the Autonomia Operaia movement, which sought to empower workers—defined broadly to include students, homemakers, and others doing unwaged labor—through decentralized local networks rather than the hierarchical political parties and trade unions that had historically neglected their concerns. The movement made good use of alternative media like pirate radio, it opposed capitalist exploitation with mischievous fun, and it had recently helped inspire spontaneous protests in Bologna. Gartside thought its strategies might be portable to London.

He’d already been reading Antonio Gramsci, the humanistic Marxist who’d opposed Mussolini and died in prison; Gramsci’s writings on cultural hegemony—the way the ruling class promotes its values less by brute force than through cultural norms imposed by social structures that he called historical blocs—were particularly pertinent to young musicians planning to change the world through rock ’n’ roll. The band renamed itself in tribute to Gramsci’s political writings—scritti politici in Italian—but changed the second word to the made-up Politti, thus evoking Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” and a whole distributary history of pop glossolalia: instances of the music’s message overloading the language at its disposal.

They began to think of Scritti Politti as not just the people who played the gigs but everyone involved with the project in any capacity; recruiting participation was the whole point. Inspired by a slogan of their peers the Desperate Bicycles—“It’s cheap, it’s easy, go and do it!”—they issued “Skank Bloc Bologna” on their own St. Pancras label with a sleeve that summarized the process of recording and releasing it, along with a detailed budget, to help other musicians do the same. They also included the address of their squat—1 Carol Street, Camden Town—and welcomed whoever showed up.

As you’d expect of an attempt to break free of imposed social structures, it was a time of all-consuming intensity, exhilarating and terrifying in equal measure. And it was a game played for real stakes: white-power skinheads and National Front thugs stalked Camden—the notorious Oi! band Skrewdriver was squatting a few doors down—and violence was constant, at gigs and on the streets. Gartside carried a knife whenever he left the squat.

Which is not to suggest that the atmosphere at home was restful. The Scritti collective functioned through constant self-examination, discussion, and debate, with the aim of detecting the occult operations of power structures in the most seemingly straightforward, ostensibly natural activities, then looking for ways to approach those activities differently. The main tools of analysis were Marxist, but antiracist and feminist critiques became central, too. In an interview with Simon Reynolds, Edwyn Collins—then the lead singer of the Glaswegian band Orange Juice, later the “A Girl Like You” guy—describes staying at the Scritti squat when playing gigs in London, remembering it as “the first time I encountered what people would now call ‘political correctness.’ They’d be talking about things that I just thought were insane. ‘Is it cool to have penetrative sex?’ Stuff like that!” Such things are not, of course, insane, or even wrongheaded; what they are is radical.

If Gartside’s self-assigned readings in contemporary philosophy gave him the intellectual equipment to handle himself in these debates, they also left him with the suspicion that the debates weren’t resolvable, owing to the inbuilt slipperiness of the language in which they had to be conducted. Similar concerns applied to the music. By then Scritti was getting noticed—they’d signed to indie label Rough Trade after influential BBC deejay John Peel started spinning “Skank Bloc Bologna”—but along with the new attention came foreclosure and diminishment, a sense that the music was being shaped by the systems and practices that propagated it. “Indie was becoming Indie with a big ‘I,’” Gartside recalls; “there was a whole way that indie music now sounded, the way that people who were into indie dressed; it shrank. It became rock music again. There was no way I wanted anything to do with that, it was horrible.”

Scritti had taken to improvising most of their sets, making up songs on the fly in an effort to de-commodify their output and stay ahead of audience expectations, but this only carried them so far. They considered more extreme measures—abandoning song forms and embracing atonal free improv, as others had done—but beyond signifying some imaginary avant-garde integrity, doing so would have cost them their basis for connecting and communicating with audiences. Besides, Gartside didn’t think that “there was anything more honest, truthful, or revealing” about an approach that relied for its appeal on an aura of gnomic subjectivity ginned up by ostensibly spontaneous expression. He wasn’t sure what to do next.

As it turned out, there was another sense in which Gartside was playing for real stakes. Throughout this period of stress and uncertainty he was drinking a lot, taking speed, sleeping very little, eating rarely and poorly. In early 1980, shortly after Scritti played a gig in Brighton in support of Gang of Four, their mates from Leeds, Gartside collapsed and ended up in the hospital with what he had every reason to believe was a heart attack. It was a panic attack. Gartside’s parents, whom he hadn’t spoken to in years, read about the incident in the press and reached out, begging him to return to Wales to convalesce, which he did.

This was an opportunity to return to first things—old records by the Beatles, the Faces, the Kinks—and to consider paths not taken. Gartside’s sister was a fan of northern soul, and had left her records behind when she moved out; although Gartside loved reggae, as did all decent UK punks, his sister’s collection reminded him that he had never paid much mind to gospel, funk, R&B, or any other music made predominantly by African-Americans, right up to recent disco and pop. Rough Trade chief Geoff Travis encouraged this new interest, getting Gartside into Prince’s first London concert; Prince’s androgynous funk, along with Nile Rodgers’ elegant latticework and Michael Jackson’s rococo lightness, began to show him ways to avoid and to challenge the “phallocentric rock music” that had become postpunk’s default mode.

Gartside being Gartside, he also needed a theoretical framework for changing Scritti’s sound, and this came from Derrida, another new enthusiasm. Derrida’s deconstructionist interrogation of the “metaphysics of presence” provided a basis for attacking a whole host of assumptions that were pervasive in the postpunk community: the idea that simple was more authentic—and therefore better—than complex, harsh better than sweet, loud better than soft, spontaneous better than practiced, emotional better than cerebral, live better than recorded. (That last binary was of particular interest given Gartside’s increasingly debilitating stage fright.) As Gartside tells Eshun, among the people who were producing and talking about indie rock,

There were ideas about music that were 19th century. It was dreadful, the discussion that went on about music—in the press, and generally, ideas believed about music and creativity. All of them being concerned with questions of authenticity, expressivity, honesty, truth, the natural. There was a privileging—obviously jazz was the greatest thing, then you had the blues, then you had rock music, I don’t know where reggae fitted in, then at the bottom of the pile was pop music.

The fact that pop was so discredited, Gartside figured, was practically proof of its untapped power to propagate radical ideas and promote structural change, while indie music’s smug insistence on authenticity limited its relevance and its ability to communicate: that’s exactly how cultural hegemony works. (In fact, indie authenticity might be synonymous with the refusal to speak to certain audiences and to say certain things.)

Gartside again being Gartside, he wrote out his analysis—pages and pages of it, “a kind of apologia, a mini thesis, or polemic”—and when the other members of Scritti Politti came to see him in Wales to check on the progress of his recovery, “I presented them with copies of this thing. It was an argument as to why we should stop fucking around at the Electric Ballroom, scratching our guitars and making farting noises on the bass, and we should make pop music. We should try and write songs. This is to put it very crudely.”

The band didn’t love it, but they went along, and the result was “The ‘Sweetest Girl’”—note the interior quotation marks—a head-snapping sonic departure from what they’d recorded previously, and an instant success: Rough Trade made it the first track on the C81 compilation that it made available to readers of NME, and a ton of people heard it. It’s a bare-bones take on lovers’ rock—the romantic, melodic, not-overtly-political version of reggae popular in London—and a song that Paul McCartney would be proud to have written. It features two bassists, muzzy dub effects, and Robert Wyatt of Matching Mole on Motown-citing keyboards; it also relegates Morley to the role of drum-machine programmer.

But the biggest change is Gartside’s voice. “It was a much-disliked voice,” Gartside recalls; “everyone hated it.” He’d dropped the working-class London accent he’d been using and replaced it with one that seemed placeless, not quite American. He also pushed his breath into his sinuses, high-pitched and low-powered; the voice gestures toward familiar R&B and funk falsettos, but carefully avoids vibrato, melisma, other signifiers of blue-eyed-soulfulness. (“Once capital secularized Gospel,” Gartside says, “it was a fascinating moment, because it wasn’t the text any more, it wasn’t ‘the Lord’ that was animating the singer and producing this stuff, it was a series of devices, mannerisms, the rest of it.”) “The ‘Sweetest Girl’” shows surprisingly little strain given everything it’s connecting: the way that power constructs gender and desire, the effects of these hidden structures on love, mental health, and political engagement. It’s a great song, an impressive declaration of purpose, and a tough trick to follow up.

Rough Trade had gotten ahead of the band with the C81 release; Scritti Politti’s debut album, Songs to Remember, didn’t come out until the late summer of 1982. “The ‘Sweetest Girl’” is probably the best thing on it, but overall it works, and it includes a couple of truly remarkable selections, including a little ditty called—here it comes—“Jacques Derrida.”

This is just flat-out one of the loopiest pieces of popular music ever put to tape, an aggregation of so many questionable ideas that it achieves a kind of critical mass. It’s a song that They Might Be Giants would be proud to have written: a bouncy cowboy hoedown over which Gartside cracks jokes like Henny Youngman at the MLA Convention. (“He held it like a cigarette behind a squaddie’s back; he held it so he hid its length, and so he hid its lack.”) Along the way he takes a shot at doctrinaire Marxists—almost certainly including his own past pre-poststructuralist self—who pore over Italian leftist newsprint with pure clarity of purpose. The fact that Gartside mispronounces Derrida’s name as duh-REE-duh (“evidence of my autodidacticism,” he explains) just makes it more perfect. Then, as it seems like it’s winding down, Gartside starts rapping.

At this point Scritti is still showing its work: listeners unencumbered by degrees in the liberal arts will hear all the hooks, but they won’t follow all the references. The approach is also showing some cracks in its plaster: as the arrangements become more sophisticated, the music seems less like the work of an autonomist collective and more like the expression of Gartside’s specific vision. To no one’s great surprise, Jinks and Morley parted company with Scritti not long after the release of Songs to Remember; a band that a couple of years earlier had understood itself to include dozens of people now consisted of Gartside alone.

Gartside’s vision of Scritti’s future was clearly incompatible with being on an indie label, and he made the decision to move to the majors: Virgin in the UK, Warner in the US. It was becoming clear that his ad hoc approach to slick pop production wasn’t going to deliver the goods; he needed to work with pros. (His summary of this realization: “It was difficult, it was expensive, go and do it!”) Gartside had recently enlisted Bob Last, the former head of the eminent but short-lived label Fast Product, to manage Scritti, and Last was raring to go; when Gartside mentioned that he wanted to work with someone who could get the kind of sound that superstar producer Arif Mardin had achieved on recent albums by Chaka Khan, Last hired Arif Mardin.

But the key recruitment came via Geoff Travis, who had introduced Gartside to a young American keyboardist and arranger named David Gamson; the two hit it off immediately, finding their musical interests to be almost eerily compatible. At Gamson’s suggestion they relocated to his hometown of New York to record Scritti’s sophomore album, bringing in drummer Fred Maher in the process. Maher too was preternaturally well-suited to the task at hand; he’d played with edgy downtown heavy-hitters like Bill Laswell, Fred Frith, Robert Quine, and Lou Reed, but also knew his way around a drum machine. Maybe more importantly, he knew how to mesh live drumming with programmed tracks in a manner that sidestepped the mechanical–natural binary that undergirded assessments of a lot of ’80s pop. After Gartside found himself the sole member of Scritti Politti, he had every expectation of completing his next album with session players; instead he quickly found himself in a real band again.

To be sure, session musicians are plenty audible on Cupid & Psyche 85, most of them presumably brought in by Mardin, who produced three tracks on the album, including the first two singles—though not the one that hit big in the US. Scritti did the production work on “Perfect Way” themselves, with Gamson and Maher handling most of the playing; Gartside ceded guitar duties to Nicky Moroch and Alan Murphy, the latter from Kate Bush’s band.

In his earlier lyrics, Gartside always keeps a toe on base with respect to critical theory; his pop tropes appear inside parentheses and (sometimes literal) quotation marks, allowing him to claim critical distance. But on Cupid & Psyche 85 he shows the courage of his poststructuralist meta-convictions: if you’re not looking for it, the theory’s not there. Or rather it is (of course) always already there, only now deprived of brackets to signify that Gartside is any less entangled than his audience in the sticky, tremulous web of sentimentality and cynicism, emotion and artifice. Songs to Remember is music about pop music; Cupid & Psyche 85 is pop music about pop music.

Anyway, whatever it is, it worked. The album is fantastic. It sold something like a million units worldwide, and Miles Davis added “Perfect Way” to his live sets.

V) Wonders

Given that one of the basic poststructuralist precepts is that despite our illusions or delusions of disinterested objectivity, whenever we encounter any new work of art or product of culture we arrive carrying the full freight of who we are, I now feel obliged to move aside the authorial curtain that I’ve been hiding behind—this tapestry of second-, third-, and first-person pronouns—and make a disclosure of sorts: “Perfect Way,” an immaculately-crafted pop song that is not only derived from critical theory but actually originates in a crisis prompted by conflict between two adjacent branches of critical theory, is extremely my shit.

I should also say that I don’t know all that much about theory. Probably two-thirds of what I know about Jacques Derrida I learned to write this essay. But I’m interested in theory, I want to know about it, and I knew enough about Scritti Politti to know that I’d need to read around in it in order to write about this song.

My relationship with theory, which at the time I just thought of as my relationship with language as such, started in high school, when I started to notice ways that writers use sound and rhythm to manage readers’ experiences. An example that struck me as particularly badass—as it is apt to strike many a sixteen-year-old boy—was “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” by William Butler Yeats. I decided to read more of his stuff, and to learn more about him.

Among the white-guy modernist poets who showed up in English textbooks, and who tended to be bankers and doctors and insurance executives, Yeats stuck out like a sore thumb. He engaged in ill-advised semi-requited love affairs, consorted with revolutionaries risking their lives to expel an occupying force, lived in a restored 15th-century tower—dude lived in a tower—in rural County Galway, and regularly communed with incorporeal beings with the assistance of his wife, a spirit medium. This all made him pretty unusual as a literary personage, but to me he seemed perfectly intelligible as what the rules of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, theretofore my principal intellectual frame of reference, called a “magic-user.” The idea that two things I was very interested in—poetry and magic—had some degree of overlap was, to put it mildly, exciting.

I read books about Yeats, including one by Harold Bloom that I thought was well-written, if light on close readings. I learned that Bloom was affiliated with something called the Yale school of criticism, which the decade-old library books I was flipping through seemed convinced was the next big thing, though they generally seemed alarmed about this. At the center of the Yale group was a faintly Mephistophelean figure named Jacques Derrida who was notorious for doing something upsetting called deconstruction and for having at some point declared that “There is nothing outside of the text!” I imagined rolling thunder, fainting ladies in Regency gowns.

This idea of there being nothing outside of the text—which, to be clear, I misunderstood—seemed to proceed from the basic premise of the magus: the seemingly solid tangible world is in fact a stack of reflections and metaphors, subject to manipulation by those who possess secret knowledge found in dusty old tomes and grimoires, knowledge that consisted of written language. Linguistic mastery, it seemed to me, meant mastery of reality itself; it made anything possible. William Butler Yeats was my Anarchy tour, I guess. Yikes.

And my experience of undergraduate education, like Gartside’s, was also frustrating, though not because my professors were second-rate or checked-out, as Gartside believes his to have been. My disappointment came partly from the fact that by 1990 deconstruction had come and gone from English departments, or had never shown up in the first place; I mostly encountered new historicists, or people whose scholarship was focused enough or whose pedagogy was responsible enough to avoid falling obviously into any particular camp. They were great; I learned a lot.

My disappointment came mostly from the fact that I was trying to make critical theory in general and deconstruction in particular mean something they did not mean. It's dumb to say, and Derrida does not say, that there’s no material reality underlying our systems of signification. It’s out there, being altered by our carbon emissions, behaving in ways our language can’t represent and our science can’t quite account for; we can infer that eventually it will kill us, since it kills everyone. It’s just pretty much impossible for us to have any direct experience of it, shrouded as it is by our brilliant yet stupid brains, our systems of signification.

Because this is the story of a one-hit wonder, you will not be surprised to learn that Scritti Politti’s mastery of pop music did not translate to unqualified success. While Green Gartside’s belief in the power of a perfect pop song didn’t turn out to be misplaced, he did fail to anticipate one important factor—which, to be fair, did not become pertinent until Scritti reached a high level of international visibility.

Simply put, the massive apparatus required to put Cupid & Psyche 85 into the ears and eyes and minds and hands of millions of potential customers did not care about the music or the musicians at all. Gartside still speaks with undimmed horror of morning TV news shows in America, and it’s not hard to imagine why: pancake makeup, withering lights, identical abbreviated dialogues with hosts who had no idea and no interest about why he was on the show. Exchanges as instrumentalizing and dehumanizing as transactions with supermarket cashiers, only worse for pretending otherwise. Worse still: the sense that the audience at home recognizes and values the fakeness as such, is watching explicitly to avoid substance and expecting to be protected from it. Worse still: the realization that Gartside’s own participation in these exchanges was no less instrumentalizing than anyone else’s. On the internet there’s a clip of Gartside bantering with Dick Clark when Scritti mimed playing a couple of tunes on American Bandstand; he looks ready to cut and run at any moment.

One might legitimately ask: what did he expect? But of course the hard part isn’t anticipating the promotional rigamarole; it’s anticipating one’s tolerance for it.

Gartside and Gamson and Maher—who, unless I’m mistaken, never played a live gig, partly due to Gartside’s anxiety and partly due to the intricacy of the arrangements—returned to the studio to record a follow-up album, Provision, which came out in 1988. For various technical and personal reasons the process was slow and difficult. The result isn’t a disaster by any means, but it feels like Gamson’s project; there’s little evidence of Gartside’s wit, few indications that anybody was having much fun. Once the album was in the can Gartside basically stopped doing music for a decade, at least in any kind of public-facing way. His mental health wouldn’t allow it.

Both Gamson and Maher had picked up a bunch of studio skills that had them in high demand, and with Scritti on indefinite hiatus they put them to use. Maher found time between drumming gigs to co-produce Lou Reed’s New York, Matthew Sweet’s Girlfriend, and the first two Information Society albums, which is a pretty good run by anybody’s standard. Gamson, justly credited as the main architect of Scritti’s mid-’80s sound, has worked consistently as a producer, arranger, and songwriter in pop and R&B, including collaborations with Chaka Khan, Roger Troutman, Meshell Ndegeocello, Kelly Clarkson, and Kesha. If Scritti Politti ends up having an enduring influence on popular music, it’s likely to be as much a testament to Gamson’s inventiveness and technical prowess as Gartside’s vision and idiosyncrasy. With the emergence of hyperpop in the last decade, that influence is currently much in evidence, particularly among artists adjacent to the PC Music label like Hannah Diamond, Sophie, Charli XCX, and Caroline Polachek; prior to starting PC Music, label head A.G. Cook ran a “pseudo-label” he called Gamsonite.

Gartside is still in the game too, having come up with ways to do music on his own terms. He emerged from his long self-imposed exile in 1999 with a beard and a labret piercing and a new album, Anomie & Bonhomie, on which he had collaborated with Gamson again, this time with stricter and healthier separation between their roles: Gartside wrote the melodies, and gave Gamson free rein on production.

Based on the evidence, one of the strategies that Gartside adopted for surviving pop music may have been to never again make another album as successful as Cupid & Psyche 85—not because Anomie & Bonhomie is bad, but because it’s peculiar as hell. It delivers two major surprises, the first being that instead of extending on the successes of Scritti’s mid-’80s output, it picks up where Gartside left off with “Jacques Derrida”: it’s a hip-hop album as much or more than a pop album, on which Gartside wisely leaves the rapping to guests like Mos Def, Lee Majors, and Meshell Ndegeocello. The second surprise is that despite the all-but-certain fact that absolutely nobody was asking for this album, and that its sheer awkward oddness makes it nearly impossible to throw casually on the stereo, if you can push through the thick layers of seriously? we’re doing this? that envelop it, it’s actually kind of good, occasionally even kind of great.

Sales of the album were not awesome, which cannot have come as a shock to anyone, and may have been a relief to Gartside, who returned to his quiet life of cashing royalty checks. Anomie & Bonhomie was his last major-label release, which may have lifted yet another burden; the passage of a few more years found him back with Geoff Travis at Rough Trade, once again implementing the cheap, easy, do it approach of his Camden Town days. Gartside plays and sings every note on the most recent Scritti album, White Bread, Black Beer, which he recorded at his London home. It doesn’t sound like a retreat or a retrenchment, but like Scritti Politti in undiluted and unguarded form: Gartside at liberty to joke, and remember, and think out loud. Even in this stripped-down mode he’s still able to create what I think of as perfect pop moments: the sense that even the details have details, better than half of which I’m missing. The sense of being overwhelmed, of having my circuits blown.

He’s playing gigs again, too, having discovered that at some point between 1980 and 2006 his stage fright disappeared.

These days Gartside tends to speak of the pleasure of making music in terms of the sense of freedom that it gives you, and by this I think he means having total absorption in your project, and almost total control within a space you’ve made for yourself. As many people who make creative things can attest, this experience often contrasts quite brutally with the process of trying to get the things we make to those who’ll enjoy or appreciate them, a process over which we have limited freedom and vanishingly little control.

This is, to be sure, largely the fault of capitalism. But past a certain point, beyond the opportunists and the clock-punchers and the hegemonic structures, we must encounter a loss of control that’s intrinsic to communication, when we just have to hope that the thing we made does what we meant it to do for some stranger whom we’ll never meet. And this is not a problem; this is the whole point. This is the pop moment, when we risk being misunderstood or scoffed at or taken the wrong way as the thing we made finally delivers our message. The risk is part of the message.

There’s an interview with Gartside where he’s talking about Paul McCartney—but not, I think, just about Paul McCartney. “The lyrics may make you wince in places,” Gartside says, “but then they should, it’s pop music.”

Martin Seay’s debut novel The Mirror Thief was published by Melville House in 2016. Originally from Texas, he lives in Chicago with his spouse, the writer Kathleen Rooney.

chelsea biondolillo: Glued in Golden Snippets [1]: “Pump Up the Volume”

Featuring brief histories of collage, sampling, and house music

The first version of “Pump Up the Volume” was a little over five minutes long, and was known at the time as a “cut up” track—a track incorporating samples mixed by one or more DJs. Cut-up is also a literary term, used to describe writing created from random words and phrases cut from a primary text, the technique, created by French-Romanian Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara (see three poems here, was later rediscovered and popularized by William S Burroughs. Tzara’s poetics were inspired by Cubist collages. Originally called papier collé (literally glued paper) by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, champions of the practice, they are generally considered the first occurrence of intentional collage in Western art history.

Figure 1: By Marcus Andrews - Author, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107683551

That first “Volume” was released to UK dance clubs by the independent label 4AD as a “white label” single—an LP without artist credit—in July of 1987. It was officially issued a month later as a double A-side 12” single, and just one week after that, as a remix, with nearly 90 more seconds of hardcore DJ scratching and samples, and this is the version that matters the most to this essay.

In fact, there are two key remixes of “Pump Up the Volume”—4AD’s UK 12”, and an American 12”, licensed by 4AD to 4th and B’way Records. Depending on which version we’re talking about, “Volume” can serve as a vehicle to tell a story about the evolution of House music or the history of sampling. Both versions owe their existence, however tangentially, to the history of collage.

Against Snobbism and Tittle-tattle [2]

In Herta Wescher’s Collage, a historical review of collage origins from 12th Century Japan to Western Pop Art in the ‘60s, she notes that the first time a Cubist painting included a pasted paper element was in Picasso’s Still Life with Chair-Caning in 1912.

Figure 2: Picasso, Still Life With Chair Caning. 1912.

Before the chair caning, Georges Braque, Picasso’s friend and colleague, had happened upon wallpaper samples, which he began using in studies for paintings, since reproducing the wallpaper by hand was time consuming. He showed his new trick to Picasso, and papier-collé was born.

Figure 3: Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass. 1912. PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3111011

In an examination of post-World-War-I collage art, Christine Poggi describes Cubist collages as “an attempt to undermine [aesthetic purity] by allowing elements of mass-produced culture to infiltrate the previously privileged domain of oil painting.” [3]

Around the same time the Cubists were dolling up still lifes with wall paper and musical scores, Dadaists collage artists Jean Arp and Hannah Hoch, among others, were s spinning dynamic compositions using found elements. These scavenged bits and the resulting compositions were in part a rejection of capitalism and the authoritarianism of traditional art values. Chance, chaos, and nihilism are hallmarks of Dada collages.

Figure 5: Hannah Hoch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic. 1919.

Early collage artists all over Western Europe appropriated text and images from newspapers, books, and magazines, but without media conglomerates to object, their work was generally considered “transformative”—a concept that the US would eventually codify into law.

Appropriating images and audio both became easier after World War II with the commercial introduction of two pieces of technology: photocopiers and magnetic tape. Both allowed for the modification, alteration, incorporation, and replication of the creative output of others. By the late 1970s and early 80s, lowered costs made this technology even more accessible[4].

Put the Needle on the Record

Which brings us to sampling. The first analog tape samples were created with electro-mechanical keyboards like the Mellotron with its dozens of short lengths of tape of pre-recorded instruments. When the keyboard keys were pressed, the Mellotron could create the sound of a flute or violin playing the note [5].

Like the Mellotron, the first digital samplers were huge and expensive, limiting their use to only few big names in music [6]. Later, portable digital samplers like the E-mu SP-1200 (1987) and Akai MPC60 (1988) could allow musicians to create songs without a studio. Sampled drum beats and fills especially saved rap and hip hop producers time and money, similarly to Braque’s wallpaper samples, making production accessible to a wider range of artists.

Figure 6: E-mu SP-1200

But before that, it was South-Bronx DJs in the mid-80s who took sampling into Dada-like collage territory by borrowing break beats from LP recordings to create new mixes during live performances. [7]

One of those DJs, Frankie Knuckles, left New York in 1977 for a gig in Chicago at an originally private gay nightclub nicknamed the Warehouse.

Figure 7: Frankie Knuckles, from https://www.gridface.com/frankie-knuckles-playlists/

DJ Knuckles would spin two disco records at a time and use a drum machine to add electronica inspired four-to-the-floor beats to extended the songs[8]. These Warehouse mixes were shortened to ’house music by local record stores. The first house record sold to the public came out in 1984, Jesse Saunders’s “On & On”.

Chicago house spread quickly, spawning subgenres as it surged toward the mainstream. House started hitting charts in the US in 1986 and from there, it swiftly infiltrated the electronic and soul club music scenes in Britain, Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, and South Africa.

Figure 8: House at NYC’s Paradise Garage circa 1980s, credit unknown

And it is at this point that it crashed into two bands and a record label.

A landmark of musical cut-and-paste [9]

Ivo Watts-Russell began independent label 4AD in 1980 after becoming disillusioned with the insincerity and exploitative nature of mainstream recording labels and the “amateurish largesse” of early indie labels like Rough Trade. [10]

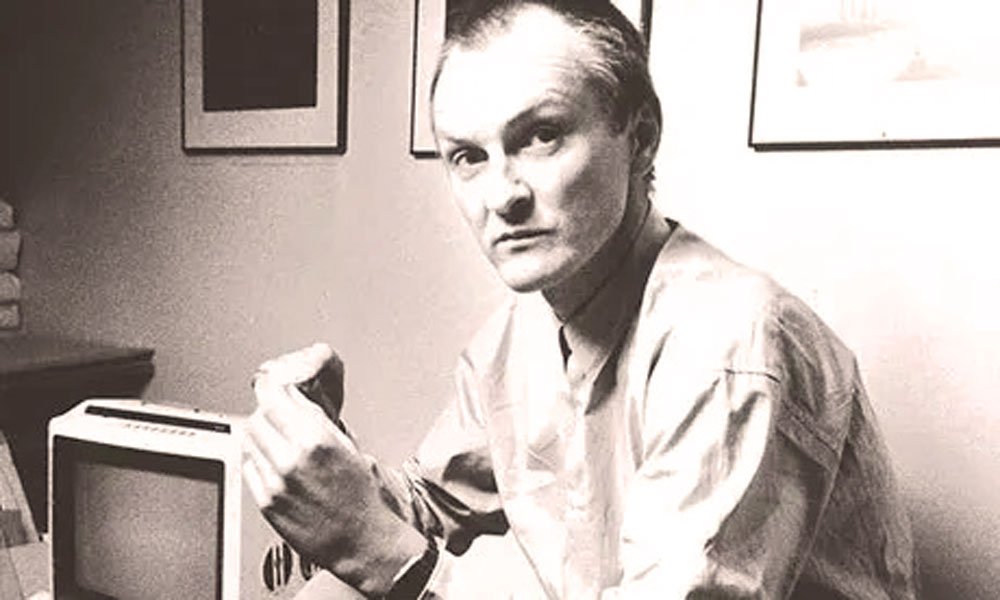

Figure 9: Ivo Watts-Russell in 1988 from arcane-delights.com

Colourbox, an electro / “blue-eyed soul” band, signed in 1982, was nothing like the rest of 4AD’s post-punk, new wave, and art-house catalog.

Figure 10: Colourbox—brothers Martyn and Steven Young

They were also often a pain in the ass for Watts-Russell. Fronted by two quarrelsome brothers, one of whom was notoriously slow at finishing albums, Colourbox crossed multiple genres with their sample-heavy 1983 self-titled EP and follow up full-length (1985), but despite competent digital sampling, sales were disappointing.

In 1987, another act, the self-defined “dream pop” duo A.R. Kane approached Watts-Russell to record an album when their label, One Little Indian, didn’t have the money to do it.

Figure 11: AR Kane's Rudy Tambala and Alex Ayuli

When One Little Indian manager Derek Birkett found out, he stormed 4AD’s offices in a dramatic and often quoted showdown culminating with his screaming, “You stole my fucking band!” To placate Birkett, Watts-Russell signed A.R. Kane for one release only.

That album, an EP, would end up being the first of two “one-offs” that A.R. Kane would record for 4AD. The second was “Pump Up the Volume,” and its B-side “Anitina,” a collaboration of a sort, made at Watts-Russell’s request, between A.R. Kane and Colourbox with scratching and sampling provided by DJs CJ Macintosh and Dave Dorrell.

The name M/A/R/R/S, [11] comes from the first names of the collaborators: Martyn Young (Colourbox), Alex Ayuli (A.R. Kane), Rudy Tambala (A.R. Kane), Russell Smith (A.R. Kane at the time), and Steven Young (Colourbox).

From the beginning, the two groups did not like working together and by the time the single was released, Colourbox was so angry with Watts-Russell for keeping “M/A/R/R/S” on the record despite all but a single guitar part from Ayuli and Tambala having been cut, that it broke the band (though they would resurface for reissues in 2001 and 2012). Watts-Russell was so angry with A.R. Kane for what he described as dreadful behavior that he never released another album with them.

As mentioned at the top of the block, it was the remix of “Volume,” that excited listeners, and that version featured a Dadaist’s dream of unlicensed samples from 26 records including among others Eric B. & Rakim, Criminal Element Orchestra, Bar-Kays, James Brown, Public Enemy, Run-DMC, and regrettably, 7 seconds from Stock, Aitken & Waterman (aka SAW).

Figure 12: Stock, Aitken, and Waterman, looking about as edgy as a watermelon

Those 7 seconds almost led to the first music sampling test case in UK courts, culminating in a 5-day injunction that halted distribution of the record, including its overseas licensing to 4th and B’way Records. After slapstick courtroom testimony and histrionic media interviews, the case was settled out of court for £25,000, which 4AD donated to charity.

But now things get weird(er). Not only was the offending sample’s source track presciently titled “Roadblock” but the sample was also understood at the time to have been sampled by SAW in the first place. The origins of the snippet of singer Chyna and saxophonist Gary Barnacle remain unconfirmed, and both have since been given credits on the track.[12]

Some in the music press accused SAW of calling M/A/R/R/S’s kettle black, since SAW themselves had earlier “borrowed” the bass line from Colonel Abrams’ “Trapped” for one of their own hits. It was also hinted that the whole controversy may have been a stunt to keep said track on the UK charts despite M/A/R/R/S’s swift advance. The track? You won’t believe it.

Adding to the rat king of appropriation allegations, some claimed that the SAW sample in the remixed UK release was itself payback for a remix of Sybil’s “My Love is Guaranteed” produced by SAW’s Peter Waterman and released the same week that the original version of “Volume” was climbing the charts as a white label. The Waterman remix, called the Red Ink mix is… uh, extremely reminiscent of “Volume.”

In the end, the SAW injunction meant that the UK radio edit and all US versions of the song wouldn’t feature Chyna’s “heyyyyy” at 3:11. But that wasn’t the only cut: James Brown’s lawyers were also waiting for the single to hit US soil, so away those went.

All told, the US remix is short over half a dozen of the UK samples. Several were replaced with samples of 4th and B’way artists (eliminating clearance issues). The song’s Wikipedia page includes a “select list”of samples that appear on the 4 UK and 4 US versions. However, there are also multiple music forums that have tried to suss out all the original sources.

Meanwhile, despite litigation, fisticuffs, and hurt feelings, “Pump Up the Volume” raced to the top of charts all over the world, reaching number one in Canada, Italy, New Zealand, and Zimbabwe. It peaked at thirteen on the US Billboard Hot 100.

Figure 13: 4/5ths of M/A/R/R/S—looking very happy to be in the same room—courtesy 4AD

Its success could have been great, but most of the people involved never saw it that way. The single dragged Watts-Russell into the ugliness of big music he’d worked to avoid. After its release, A.R. Kane went on to record albums on other labels, though none came close to “Volume” in reach. Colourbox had initially hoped to tour as M/A/R/R/S, but A.R. Kane demanded £100,000 for the rights to the name which Martyn Young refused to pay.

Figure 14: Pump Up the Volume (movie)

And so, “Pump Up the Volume,” a collage of illicit hip-hop and soul samples and the UK’s first single capitalizing on American House music’s popularity, became a one-hit wonder of epic proportions for three bands. The anthem-ness of it is unmistakable and the beat is infectious. Eric B.’s titular line was even borrowed for Allan Moyle’s 1990 teen-angst-meets-pirate-radio film. In 2020, pop culture magazine Slant ranked it 18 in their list of 100 Best Dance Songs of All Time . Despite its indisputably indie origins, cut-up structure, illicit and combative foundation, and crunchy, soulful cuts, it remains a classic Top-40/dance crossover hit, most popular in my town, anyway, with cheer squads, aerobics classes, and tailgaters.

[1] Taken from a quote by A. Grishchenko describing Russian painter and collage artist Alexandra Exter—1913. From Herta Wescher, Collage. (1968)

[2] From Marcel Janco, Zurich Dadaist

[3] Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage. 1992.

[4] For more on early sound reproduction, see this very weird bit from the 1979 BBC documentary, “The New Sound of Music”

[5] Something the Casio SK-1 would make available to anyone with $100 in 1985, including my parents who bought one for me.

[6] In 1983, Herbie Hancock demonstrated his Fairlight CMI to Maria and the kids on Sesame Street

[7] from https://www.thomann.de/blog/en/a-brief-history-of-sampling/

[8] There isn’t the space here to talk about the history of disco, but it is worth noting that it was, in part, a response to the isolating consequences of race riots and homophobia in the ‘60s. Early discotheques were often private night clubs, safe spaces, for predominantly gay people of color.

[9] From Michaelangelo Matos, “How M/A/R/R/S’ ‘Pump Up the Volume’ Became Dance Music’s First Pop Hit, Rolling Stone, July 2016

[10] Richard King, How Soon is Now: The Madmen and Mavericks Who Made Independent Music 1975-2005. (2017)

[11] Also stylized as M / A / R / R / S, M /A /R /R /S, M A R R S, M-A-R-R-S, M. A. R. S. S., M.A.A.R.S., M.A.R.R.S, M.A.R.R.S., M.A.R.S.S, M.A.R.S.S., M.a.r.r.s., M/A/A/R/S, M/A/R/R/S, M/A/R/R/S., M/A/R/R/S/, M/A/R/S, M/A/R/S/S, M/a/r/r/s, MARRS, MARS, Maars, Marrs, Marss, and The M.A.R.R.S. (https://www.discogs.com/artist/12590-MARRS)

[12] Hear the extended version here, including Chyna and Gary in the first 3-10 seconds of the song and again at 3:05-12.

Chelsea Biondolillo is the author of The Skinned Bird: Essays and two prose chapbooks, Ologies and #Lovesong. In the summer of 1987, she was 14 years old and not even remotely cool enough to know about house music, but she went to her first real dance party right around that time, on the campus of Central Michigan University.