round 2

(10) warlock, "all we are"

defeats

(2) cinderella, "don't know what you got (till it's gone)"

327-132

and plays on in the sweet 16

Read the essays, watch the videos, listen to the songs, feel free to argue below in the comments or tweet at us, and consider. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchshredness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/16.

ANDER MONSON ON CINDERELLA'S "DON'T KNOW WHAT YOU GOT (TILL IT'S GONE)"

- Because I wore my Cinderella shirt to the Dokken show two weeks ago and did receive some glares from men.

- Because in my enthusiasm for these bands who coexisted and even may have crossed paths on the chart or on one bill or another, I’d forgotten how much some people (mostly men, mostly self-styled serious hardcore men) dislike Cinderella. I’ve registered that while talking about the tournament with people (mostly men) who, when presented with the list of songs, take exception at the number of power ballads we’re repping here (by my count 11 of 64):

- “Alone,” “Mama I’m Coming Home,” “High Enough,” “Every Rose Has Its Thorn,” “Home Sweet Home”, “Wanted Dead or Alive,” “Close My Eyes Forever,” “Don’t Know What You Got,” “Ballad of Jayne,” “Don’t Close Your Eyes,” “Fly to the Angels”

- Because “Don’t Know What You Got (Till It’s Gone)” is Cinderella’s best moment in their best mode, which is the moody ballad, and, you know what, it's okay, and in fact it's better than that: it's awesome.

- Though the band’s sound was originally heavier (consider “Shake Me,” their debut, and its follow-up, “Night Songs”), when “Nobody’s Fool” hit #13 on the Billboard Top 40, they must have known that they had something.

- Those earlier songs, and their videos, and their look drew way more from the Crüe and Poison than I remember, and, though they’re still pretty good, they blend into what everyone else sounded like at the time, which is probably why Cinderella ends up, more often than not, at least among the men I know, as some kind of milquetoast referent, at which point men like to explain the power ballad to me ("because you have nostalgia for how you got freaky with some girl in high school while it played").

- It's hard to be metal when your best early ideas, like the video iconography and the fairy tale stuff (clocks, stepsisters, midnight curfew, etc.) mean that you're willing to poke fun at yourselves:

- Consider the fact that, in the video for “Somebody Save Me” the guitarist wears a Poison t-shirt, and at the very end, the weirdly way overdressed hot stepsister girls diss the band, embarrassingly, in favor of Jon Bon Jovi (helpfully wearing a Bon Jovi jean jacket, as if we didn’t know who he was). And can you blame them? Cinderella was no Bon Jovi, the men explain to me.

- And maybe that's why Bon Jovi lost to Dokken, and maybe that's why Cinderella ought to keep on playing?

- It's hard to be metal when your best early ideas, like the video iconography and the fairy tale stuff (clocks, stepsisters, midnight curfew, etc.) mean that you're willing to poke fun at yourselves:

- Then comes second album Long Cold Winter, featuring first single “Gypsy Road” (defeated first-round opponent: we salute you), which broke dramatically into a whole new—and bluesier territory. But shortly thereafter, we arrive at “Don’t Know What You Got,” a straight-up power ballad that, alongside a few others (most obviously “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” and “Home Sweet Home”) defines the genre.

- Because Cinderella was never quite cool. Because they weren’t ever particularly metal. Because they were beautiful. Because they weren’t threatening enough to trouble my parents. But they sold a lot of albums, probably because Tom Keifer could write songs and because they figured out what they were good at, and did it, and a lot of people, not just the men who explain the rock to me, liked it—and like it. Because their pouty, moody look suited them (and me) in ways that shaded into my eventual interest in goth (see also next year’s March Vladness, the goth bracket). In retrospect I’m not sure that any of my friends liked Cinderella at all, or at any rate, the few who would admit to it may have just been signaling dissent. Because the cool kids were choosing the more aggressive bands, the ones most likely to impress their (non-Canadian) girlfriends or trouble their teachers.

- Because power ballads were never cool either. Not then, not now.

- Because they’re accessible. Because they seem simple and don't fluff their feathers quite as much as the shreddier tracks. (Consider The Case of the Listenability of Yngwie Malmsteen, the last Encyclopedia Brown book I read.)

- Because whatever the reason, it was the ballads that got me. I remember loving them, and I still do, and don’t mind saying so. I don’t care how wussy that makes me sound.

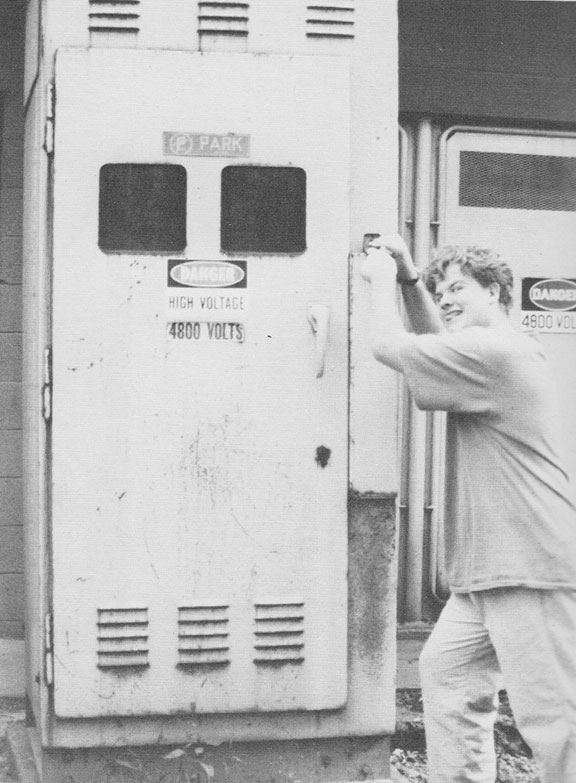

- Because I also realize how this looks against the fucking WARLOCK gripping Doro Pesch in the album art my wife is repping at right.

- Because it pleases me to be playing the wussy card against her (and because there's no way I'm going to out-shred fucking WARLOCK and Megan, I'm realizing).

- Because more often than not, for many of these bands, the power ballad is the thing we remember, because it is the thing that endures past adolescence, because no one is ever going to shred as hard as Doro or Vai or Malmsteen, my friends explain to me.

- Because I like moody things and because hair metal is as much a mood—a posture—an affect—as anything else. And because the moody ballad is an undersung element in what we’re talking about in this tournament.

- Because you voted out "Home Sweet Home."

- Because you voted out "Every Rose Has Its Thorn."

- Because you voted out "Fly to the Angels" and "Alone" and "Ballad of Jayne" and "18 and Life" and "Wanted Dead or Alive"

- And because you're for sure voting out "Mama I'm Coming Home" and because you're probably going to vote out "Close My Eyes Forever" before too long.

- Because this may be the last power ballad standing.

- Because I realize that may constitute grounds to vote it out.

- Because, regarding moodiness, Cinderella’s album titles (Night Songs, Long Cold Winter, Heartbreak Station) say it all, do they not?

- Because Cinderella can bring it (key for defusing the resistance to sentimentality in the hardest metal heart, and because that sentimentality needs cherishing and protection, that’s probably why all the remonstrations at the number of power ballads and the general utterances of woe from the men and some of the women in my life).

- Because the vocals here are tough karaoke sledding: Keifer’s shriek of a voice is something you just don’t want to do. It’s no surprise that he’s lost it intermittently (due to “paresis of the vocal cords”), and he’s undergone several surgeries to get it back for you). Keifer’s feeling it. Keifer suffers.

- Because his feeling it is proxy for our feeling it. Because his suffering is the thing that leads to our suffering.

- Because, sure, it’s a little self-pitying, but it’s also grand. The video’s all landscapes, wide and empty, and helicopter shots of the band with their unplugged instruments against the background of California’s Mono Lake, a park eventually defunded by the Bush administration (bigger tragedy for sure than voting down "Every Rose Has Its Thorn"). And if they’re miming the solo on an unplugged electric guitar, we know how that goes.

- Because they actually have in the piano an instrument that does not need an amp to sound.

- But really because the chorus.

- Because the chorus rules.

- Because the motherfucking chorus rules.

- Because the chorus is not just a chorus but a position statement: at first it's familiar: “Don’t know what you got till it’s gone.” That may be a cliché, but it’s a good one, the sort that we’re continually living, and the kind of thing that reminds you why we made clichés: because they do useful work for us. In the aftermath of the relationship’s wreckage, all we are for a little while is broke. And we romanticize the past. We like to feel our feels and keep on feelin until the feelin does what it’s supposed to do: it coats the pain and eventually recedes. But this song doesn’t recede. It’s in the ditch after the car wiped out, and it's playing, and it’s just looking up at the sky. And it knows what it’s feeling is the thing it’s after, not the thing that caused the wreck, and whatever clean-up follows it.

- Because I want to tell Keifer: some things are better in the past. And even if it wasn’t me, it was you, whatever, and you “Don’t know what it is [you] did so wrong,” there’s that moment when you can just fucking feel like it was over. And maybe it was. Maybe it is. But it feels good to think that maybe there’s still something there, a scrap of hope. That’s all fine. Hoping is good.

- Because Keifer’s 14 years older than me, I don’t have to tell him these things. He knows.

- Because let’s keep talking about the excellence of the chorus, in which the final line turns things again: “Now I know what I got / it’s just this song”.

- Because: “Now I know what I got / it’s just this song”.

- Because that’s interesting. Whatever’s left after the wreck of whatever relationship this is: just this song, the art that I’m in the process of creating, the mourning that I’m making, whatever ring the song’s left on you, thirtyish years on.

- Because fuck yeah.

- Because that’s the equation underlying art. It’s not easy to say out loud, much less to put in a millions-selling rock song on a triple-platinum album in a genre that was derided at the time (and even now by its detractors) for its emptiness.

- Because it makes a profound statement about art and loss without having to overcomplicate it (unlike, perhaps, the engine of this essay which I know tends toward the maximal—just be happy this format does not accommodate footnotes).

- Because the MA thesis of my friend Matt Vadnais, who also cops to some Cinderella love in his essay on Dangerous Toys (& if the song was rightly defeated, still let's give his excellent essay another spin), had to be bound in two volumes, which is probably some kind of academic record.

- Because, unlike this essay, the chorus is not fussy and not apparently technical. Kiefer doesn’t have to work for the rhyme: gone chimes fine with song. Everything is here in its right proportion. It’s grand but not grandiose, big but not bloated (or at least to me not bloated, or not in a bad way anyhow: there are times when bloat can sustain you too). It’s got sentiment without sentimentality. And here I am, thirty years later, still thinking about just what I got—what we all got—when we got this song.

- Because Tom Keifer’s pouty mouth delivering it seems to open for all of us.

- Because Tom Keifer's mouth and sweet, subtle rhyme and what it represented constituted a dissenting opinion in the sea of hair metal that seemed to be the only thing on offer at the time.

- Because Tom Keifer’s mouth's vocals here are good—dude is feeling them for sure—but they’re not too showy, unlike the vocal and physical gyrations that lesser songwriters might require by way of performance to suggest emotion. These guys’ amps aren’t pulling the thunder from the gods (in fact in the video nothing is even plugged in, in that way you notice at some point as a teenager and wonder how easy it is to believe in an artifice).

- Because the more I think about it, the more I’m beginning to think this is the best of the power ballads, and is in fact only one of three power ballads left.

- Because while you could argue that Shredness and Hair Metal is all about excess, and you wouldn’t be wrong, then you’re basically arguing that “Cherry Pie” should be up against “The Lumberjack” in the final in a battle for the least subtlety, which makes me barf a little bit in my brain.

- Because the power ballad rules and can't we just admit it?

- Because it's a little silly, and it's okay to say so.

- Because it expresses an important thing it's easy to mock it.

- Because if you really hate the power ballad I think you hate a little part of yourself.

- Because the guys form Cinderella are from Philadelphia. Because they had to earn their cool. Because they worked for it.

- Because cool is exhausting (and aping it produces little that lasts).

- Because Bruce Mau's "Incomplete Manifesto for Growth."

- Because we're capable of growth, right? (The author thinks on his better days.)

- Because there’s a reason why we romanticize the past, how you romanticize that relationship you had with hot whoever from high school or college, you know the one that comes back unbidden and reveals something about yourself when you believed yourself to be more free: how free were you, anyway? It wasn’t all that good. There’s a reason why it was over, too.

- Because it's okay to understand that and not to let it (always) own you.

- Because there’s a reason why you still think about her and why you’re can still access that feeling.

- Because my friend Paul tells me that in the wake of his divorce, he's reconnected with the first girl he ever kissed and there is real light in his eyes when he says this.

- Because he was devastated before.

- Because let's hear it for the Pauls.

- Because memory and because hope.

- Because sentiment and because the power ballad is the best vehicle to tap it.

- Because songs are the quickest way to get us back to whom we think we used to be.

- Because you are—I am—we are—are some sentimental motherfuckers way down in there somewhere.

- Because you were is because you are.

- Because what you say and what you vote don't have to be the same thing.

- Because listening to “Don’t Know What You Got (Till It’s Gone)” on cassette was a lossy enterprise (remember how those media degraded with each listen?), as is living, and as is remembering the past or trying to reinhabit it or take it apart.

- Because nothing lasts, not really, and it's nice to be reminded of that.

- Because in spite of that, what you took of “Don’t Know What You Got” is yours and always will be, whether or not it wins this tournament (or even this matchup).

- Because in the end you know what you got, and hopefully it’s something good (like a matchup in the second round against an excellently shreddy song as represented by a brilliant essay by your wife and co-committee member rocking some bangs), but if it’s not, after everything, it’s just this song, and that’s something too.

- Because even if it's not, you've got something inside you that can still flower.

- Because Pauls know that.

- Because Tom Keifer knows that.

- Because you know that.

- Because you know what to do.

More early AC/DC than Cinderella, yet…

One half of the March Shredness Selection Committee, Ander Monson is all in for Cinderella, among other enthusiasms.

megan campbell on warlock's "all we are"

I was a mere metal dilettante back in the 1980s: a junior high kid who eagerly consumed whatever MTV offered in prime time, but rarely bothered with Headbanger’s Ball, even when I was allowed to stay up late. I was dimly aware of bands like Iron Maiden and Megadeth, and staunchly assumed that they were scary and I would hate them. My tastes were solidly in the Poison/Whitesnake/GnR camp, and often much more embarrassing than that (Winger’s “Seventeen,” anyone?). Thus, I began my Warlock/Doro journey as an adult, without the rosy glasses of fan nostalgia. I did, however, feel a tinge of righteous anger: Why was young me only shown the dude bands? Huh, MTV? Let’s talk about women in metal! Let’s talk about the dearth of female role models for my 13 year-old hair metal-loving self (because I did love it, until “Cherry Pie” killed that love by truly sucking, and “Smells like Teen Spirit” buried it by rocking out in a whole new, leather-free way). Why DIDN’T I know about Doro? She’s The Metal Queen of Germany, for fuck’s sake! BECAUSE OF THE MTV PATRIARCHY, THAT’S WHY!

Propelled by the general awesomeness of the video for “All We Are” (more on that later), I dove right into Doro Studies. But something unexpected happened: the deeper I dug in, the less I found. Doro is . . . incredibly earnest. She’s a vegan! She loves music, especially rock music, of course. She LOVES her fans. She donates heavily to a charity for women and girls. She has some training in graphic design, and she paints in her free time. She loves martial arts, especially obscure ones, like Filipino stick fighting. As an aside to all of these fascinating facts, she needs you to know that no one ever treated her badly: the men were all so respectful! At a certain point I was confronted with an uncomfortable dual realization: Doro truly was the role model my dumb and undiscriminating teen self needed, but that same self would have had no interest in her.

Young Dorothee Pesch was only 16 when she started her first band, its name morphing from Snakebite to Beast to Attack, before finally settling on Warlock in 1982. The band’s lineup also shifted around: by 1982 it was comprised of Doro, Peter Szigeti, Michael Eurich, Thomas Studier, and Rudy Graf. They found a manager and recorded their first album, Burning the Witches, in 1984. Two more albums—Hellbound and True as Steel—followed, along with some success among the metalheads of Europe. The single “Fight for Rock” (off of True as Steel) got American airplay as well. In 1986, Doro was the first woman to front a band at a Monsters of Rock show—it was held at an English castle and Warlock played with Motorhead, Def Leppard, Ozzy Osbourne, and the Scorpions.

Triumph and Agony, generally considered their breakthrough album, appeared on the scene in 1987. Warlock had an almost entirely new lineup by then, as Graf, Szigeti, and Rittel had all left and been replaced by Niko Arvanitis, Tommy Bolan, and Tommy Hendriksen. Doro, with her long blond locks and truly excellent rock vocals, was the band’s main draw, a fact emphasized by the album’s GLORIOUS album art:

Two singles from the album made it into heavy rotation on Headbanger’s Ball: “All We Are” and “Fur Immer,” a German-language track with a video set in the Louisiana bayou. However, the album fell a bit flat with US audiences. Metal purists found it too poppy, and its crisp production had none of the genre’s trademark sludginess.

Thirty years on, Triumph and Agony feels like an absolute time capsule from its era: short (just 40 minutes in total), with that careful mix of wheat and chaff I associate with The Time Before Cassingles (to say nothing of iTunes). There are a few stadium-ready rock bangers, a couple of power ballads, and a “political” song (“East Meets West,” the album’s weakest effort, ahem). Triumph and Agony wears its mainstream ambitions on its sleeve, which had to be one more mark against it in the metal community. I personally listened VERY KEENLY to lyrics like “My heart is a lion / That no-one can tame” (from the middling power ballad “Make Time for Love”) hoping to glean a little more insight into Doro’s mind; my only observation is that she, along with her band, had rather perfunctory feelings about ballads. By 1988, Doro was the only original member of Warlock left in the band—she fought to retain the name, but eventually bowed to record company pressure and changed it to, simply, Doro. She has continued to both tour and occasionally record, including a 2000 album titled Calling the Wild, which features a cover of Billy Idol’s “White Wedding.” Doro wears a white wedding dress in the enjoyably Goth-lite video, but I couldn’t help but note that there is no groom:

Warlock/Doro’s career bio is the essence of moderate, workmanlike musical success, but let’s forget about that for now. Instead, travel with me to 1987 Los Angeles, specifically the LA River Basin, setting of the video for “All We Are.” There weren’t a lot of great hair metal videos as of 1987 (fight me)—I mean, there’s Ratt’s “Round and Round,” some Van Halen, and then a lot of bands trying (and failing) to re-create the antic level of David Lee Roth. But this video? This is a great video. A ghoulish warlock magically stalls a stretch of LA traffic, and beams Doro and band onto a makeshift stage. There’s a shot of Doro’s leather-clad crotch, which I am going to go ahead and call feminist crotch parity. There’s a gratuitous explosion. Eventually, the stunned drivers and passengers exit their vehicles and begin to ROCK, because this was before we were all dead inside. “All We Are” is absolutely the best track on Triumph and Agony, a call to rebellion that aims higher than teen clichés: “I know you know we’re all incomplete / Let’s get together and let’s get some relief.”

Because I’d never seen this video before last summer, I embraced Warlock with a welcome surge of “There’s cool stuff I never knew about!” energy. I suppose on some level I was hoping to unearth some L7-style, tampon-throwing, riot grrl anger. But not so much. Interviews with Doro (at least, the ones in English, which is not her first language) have a numbing sameness. In them, she pleads her love of music, politely demurs to answer women-in-rock type questions, and praises her fellow musicians, often including nice anecdotes about Blackie Lawless (of W.A.S.P.) and Lemmy from Motorhead. She says things like: “That’s really why I’ve never been married or had any kids; the music is always the most important thing to me. And the fans! Music is always what I wanted to do.” The wall around her personal life is inviolable, the interviewers deferential.

One of the only upsides to my long and storied love/hate relationship with the website Jezebel is its frequent dissection of the Cool Girl archetype. You know her: she’s a girl but she’s, like, cool. She likes sports! She not prissy about her hair, like other girls. She HATES drama, just like you! She won’t get after you for going out with your friends too much, or drinking too much, or whatever too much. She also will daintily refrain from parsing the point at which coolness becomes inextricable from self-abnegation. I’m as guilty as anyone of Cool Girl-ing my way through my 90s youth, and it was such a relief when someone put a name to this particular coping mechanism. Thus, adult 2018 me has to wonder: is Doro truly an earnest, rock-loving German born under a lucky star, or is she Cool Girl-ing us all?

She was certainly careful never to allow herself to be portrayed as a plaything—the ignominious and inevitable fate of video girls and groupies, who must have represented about 99% of hair metal-adjacent women. Remember that album art? Multiple sources thoughtfully noted that it was created with her full consent, thank you very much. Videos and other footage of her with the various members of Warlock always depict an easy camaraderie—no winking machismo on the part of the men and no cutesy deferring to the lads from Doro herself. But also no real sense of who she is.

As far as I can remember, I shed my desire for a leather bustier and donned my 90s flannel without any lingering sadness. But this left my teenaged assumptions about hair metal more or less unexamined. My junior high self had eagerly bought into a party-hard narrative that I now realize was mostly a fiction (as well as particular to hair metal; real metal is nerdy). Hair metal required not just leather and guitars, it also demanded a carefully cultivated veneer of loucheness, one that was sometimes real (ahem, RATT), sometimes tragic (Steven Adler, Robbin Crosby, Steve Clark, Jani Lane), but often just a pose—a pose that Doro (and women in general) were wise to avoid. In fact, I wonder if it’s a pose even available to women. Drinking, drugging, and banging groupies (of any gender) certainly wouldn’t have added to a woman’s cachet in the 1980s (and maybe not now, either). Once I started looking, I couldn’t help but notice that the metal women of the 80s treaded carefully indeed around this issue. Take, for example, the Vixen video for “Edge of a Broken Heart,” one of the best-known hair metal tracks by a female band. It features them performing in sexy costumes, sure, but the off-stage footage includes such wild and crazy things as working out, cavorting in a kids’ playground, riding a tour bus with pen/notebook in hand, and chastely kissing their producer Richard Marx on the cheek.

It’s probably not surprising that the virgin/whore dichotomy (which is what we’re talking about here) applies to hair metal, but for me it brings up a more complex problem: if women in hair metal were chiefly depicted as party favors for male band members, then what exactly was the role of women musicians in this genre? Refusing to be objectified is well and good, but where does it leave you? If we believe Doro—unmarried, childless Doro, with her extra long pale blonde hair—there was plenty of room on the stage for hair metal women. But where is the space for them in our collective memories of hair metal, amid all the cleavage shots and penis shaped microphones and hip thrusts? If women had to sidestep so many of the trappings of the genre, doesn’t it become a little too easy for the memoirists and cultural historians and music writers to sidestep them and decide: Well, she wasn’t really hair metal. Or metal. Or anything.

And so we are left with: Doro the Unknowable, Doro the Pure. Musician. Vegan. Painter. Leather bustier-wearer (the bustiers are custom made of vegan pleather by fairly paid artisans). No one ever treated her badly, okay?

Megan Campbell is one half of the official March Shredness Selection Committee and the proprietor of Bad Cholla Vintage.