round 1

(8) Glee, “Teenage Dream”

denied

(9) Tori Amos, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”

422-394

and will play on in round 2

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/9/22.

let’s go all the way tonight: moira mcavoy on glee’s “teenage dream”

I had two reactions to the realization that the covid-19 pandemic was going to ravage the world—spend $300 on non-perishable food at Target, on Leap Day, just in case, and begin rewatching Glee from the beginning. I’ve long joked that watching more than an isolated episode or two of the show operated as one of my surest cries for help, but it was a reasonable reaction—it was familiar and nostalgic, which is comforting, and is the only show I’ve watched that was unhinged enough to make the pandemic’s reality tolerable to my illness anxiety-addled brain.

For the uninitiated, Glee is the improbable breakout hit musical dramedy series which dominated both Nielsen ratings and the iTunes charts from 2009 to 2015. The show centers around the New Directions, a downtrodden glee club at a WMHS in Lima, Ohio; predictably, each episode featured an abundance of singing, with the club tackling both classics and contemporary hits both in competition & rehearsals as well as a plot devices to move along the stories, further develop the ensemble casts’ personalities, or both. At its best, the show was a deft mix of humor and heart highlighted by showstopping earworms and surprisingly successful mashups. The writing and cast carried their characters with care and self-awareness, letting out little hints that everyone is in on the joke, such as the moment in the first few moments of the pilot when Artie, a student who uses a wheelchair, points out that it’s ironic that he has been given the solo in a rendition of “Rockin’ the Boat”. It is likely responsible for both the revival of interest in a cappella groups–arguably setting the stage for the popularity of the Pitch Perfect film series–and for the mash-up fad that overtook YouTube and SoundCloud in the following years. The cast mounted sold out arena tours in its heyday, and the show’s meteoric popularity helped catapult Ryan Murphy to his status as a perennial showrunner under Fox’s auspices. Nearly seven years after the show’s finale, Glee is still tied for the most Billboard Hot 100 entries of all time, thanks to a whopping 207 formally released cast recordings charting.

This is not to say Glee is necessarily good. More often than not, the writing moved past dark humor to objective cruelty, many plotlines were gallingly implausible, the characterization became wildly inconsistent as additional seasons were added to the show’s contract, and the musical numbers that were not Billboard hits? The range runs from “forgettable” to “an absolute aberration of music and human decency” either in concept, execution, or both. This can be attributed, in part, to the fact that Glee was not supposed to exist, at least not in the six-season television show structure it ultimately assumed. Ryan Murphy, then mostly known for his work on Nip/Tuck, had originally pitched Glee as a standalone film, a dark comedy centered around jackass-written-as-hero Will Scheuster, the floundering director of the New Directions and his attempts at corralling a band of misfits and queen bee’s into something cohesive and victorious. That sort of format would have been a better showcase of Murphy’s vision for the project, I think—eviscerating one-liners, characters that were caricatures of the most stereotypical players in any American high school singing songs just earnest and well-performed enough to have you rooting for Will and his crew of underdogs. The pilot—which I personally believe is one of the best pilot episodes of the twenty-first century—was even shot as such, its lighting, writing, and production mirroring the energy of the great coming of age comedies of the 2000s in whose tradition it was trying to follow. No, we were never meant to hang around McKinley long. So what gave the show its staying power?

The most enduring fascinating aspect of Glee, beyond its absolutely ridiculous plotlines and delightfully hateable characters, is that the music is nearly entirely covers. A handful of original songs surfaced throughout the show’s tenure–though more often these compositions were to serve as comedic relief, such as diva Rachel lamenting only childhood as a life-defining plight, or Mean Lesbian cheerleader Santana mocking human sunshine Sam Evans’ giant lips under the guise of a sultry ballad–but the heart of Glee’s power laid in the writers’ ability to weave songs into the plots, or sometimes to build plots around them. Glee’s incorporation of songs frequently felt similar to making music videos out of songs on your walkman in your head in the backseat of the car, a reclamation of something universal into something personal. The covers did something deeply appealing to the show’s teenage audience; it gifted the characters agency over their stories and the characterization and often allowed them to be empowered in the face of adolescent tumult, such as a breakup or homophobic bullying.

The latter serves as one of the backdrops for the sixth episode of season two, “Never Been Kissed.” Kurt Hummel, the only out gay student at McKinley, has become the primary target of closeted jock-bully Dave Karofsky’s ire, and despite his efforts, the combined abuse from Karofsky and general homophobic jabs from the other guys in the glee club is getting to him. In a moment of desperation, Kurt seeks to transfer to a safer space, an unrealistically egalitarian all-boys school, Dalton Academy. Enter the Warblers, the school’s so-called rockstar a cappella group, helmed by the disarmingly charming Blaine Anderson, Kurt’s immediate crush and eventual husband. Blaine welcomes Kurt to Dalton with casual ease, smirking while referring to him over and over as “new kid” and briefly answering Kurt’s questions about a current ruckus in the halls—the Warblers are about to perform.

The Warblers play an interesting role in the Glee Cinematic Universe. In their introductory episode, Kurt quips that everyone on the team is gay—an observation which is quickly and comically refuted by the extremely queer-coded men on the team saying they have girlfriends. Blaine is one of the few out gay members of the team, and yet, thanks to Darren Criss’ undeniable charisma, Blaine is also a further point of heterosexual desire for viewers and characters alike. The show riffs on this numerous times, with gaggles of girls from sister schools and leads such as Rachel and Tina alike falling for him over the span of criss’ tenure on the show. He is the ultimate conduit for desire and accessibility, the perfect vessel for any sort of queer longing.

The vast majority of things that happened on Glee were entirely removed from any iteration of reality; the production quality of the New Directions multitudinous musical numbers (both in rehearsal for competition and in their everyday lives) is the most consistently jarring. The contrasting implausible grandiosity and polish of the McKinley high numbers is part of what gives the Warblers and their off the cuff a capeplla so much charm. Sure—the simple-but-cohesive choreography raises some eyebrows, the tendency to burst into song would likely be frowned upon in a school with such an upstanding reputation as Dalton Academy’s, and it defies statistics that there is a THIRD high school with this much musical talent in the same general area of Ohio. But the notion that a handful of guys have a similar enough taste in music to be familiar with the same sort of songs and know how to spontaneously harmonize beautifully after frequently rehearsing together? A pass for grounded plausibility in and out of the Glee cinematic universe. More than just being semi-realistic, the Warblers make their music seem effortless.

But we—Kurt and the audience—don’t know any of this, not yet. Now, the two walk down the hall, hand-in-hand in slow motion, until they reach a crowded library-lounge filled with smiling, excitable students, where Blaine then leads the Warblers in an impromptu rendition of noted pop masterpiece and anthem of gay longing, Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream”.

Fewer things are queerer than unabashed longing and a sense of temporality, the two main ingredients of many of pop music’s all time greatest hits, including “Teenage Dream”. The song opens with a single guitar chord, the instrumentals multiplying in measure as the first verse builds and Perry’s desire grows, bursting at the chorus into full pop bliss as the singer fully surrenders to her longing and is moved to confession. The composition, to me, perfectly mirrors the rhythms of falling in love. A breath hitched and held when luck allows you to see your crush’s smile; a fluttering heartbeat whenever you get to have a conversation and your connection deepens; the clarity and simultaneous trepidation that sits in the core of your stomach upon realizing how much this person means to you; the ecstasy igniting every nerve ending when you give into the possibility that maybe, just maybe, all of this could be reciprocated, too, that you’ve both simultaneously been struck by lightning.

Part of “Teenage Dream’”s queer charm lies with the track featuring ungendered pronouns, instead addressing the beloved simply as an admired “you” and an aspirational “we”, allowing the listener to imagine whoever and whatever they desire while they listen.

No regrets, just love. You could be young forever. These simple sort of sentiments, desire laid bare in obvious jubilance, entice you to fall in love deeper than you ever thought possible because it helps you believe it’s the most natural thing in the world.

I didn’t know what I wanted from love as a teenager. I didn’t even know what love was supposed to look like. And who could blame me? I was coming of age during my parents’ drawn-out divorce in the era of Team Edward v Team Jacob. It’s hard to discern what’s healthy, what’s aspirational, when the examples available to you include things like the unsalvageable love of two people who care deeply for each other yet are incompatible and impossibly handsome, nearly-abusively possessive young men too absorbed in their own senses of duty and honor to see what their beloved deserves or needs.

More than this, I also had yet to realize that I was queer. Of course, on some level, I knew—I’d taken and re-taken innumerable poorly-coded personality quizzes named things like “r u gay?” and “if you score more then 60 on this quiz ur a lezzy” and consistently gotten results saying I was bisexual—but I didn’t KNOW. It was the mid aughts; I lived in southern Virginia and went to a tiny Catholic school. I was afraid of what these results could mean, all at once exhilarated at the possibility of something resonating on that level and so deeply terrified at what would come as a result of that resonance. I spent nearly every night huddled under the green and pink paisley covers in my bedroom wishing, willing, begging for this thing about me to change, literally trying to pray the gay away.

So much of being a teenager is not knowing who you want to be; it’s much more daunting when you’re constantly bucking at any discoveries of who you might be. I was obsessed with love and yet I didn’t know what I wanted from it. I wanted distance and I wanted intimacy. I wanted to be desired but to be alone. I wanted a boyfriend, a girlfriend. I wanted to BE a boyfriend, a girlfriend. It was too much for me to square in my mind. I fell in love with so many people who could never love me back, building walls without even realizing, protecting myself from the realization of dreams I wouldn’t dare admit to myself I was having. I was overwhelmed, but I knew, deep down, I wanted to feel like I’d been struck by lightning.

“Be my teenage dream tonight” Blaine sings directly at Kurt (and to the audience, too) with so much charisma that you can’t help but acquiesce and want to run away with him tonight, too. The Warblers’ entirely a cappella rendition of the song elevated its intensity, the emotional pulses shining through thanks to staccato backing vocals and Criss’ dynamic solo performance. Stripped of the instrumentals and the production, we have unadulterated longing and exhilaration.

As the camera pans wide and out of Blaine’s gaze, we see a room full of boys pumping their fists, clumsily dancing without any hint of embarrassment, the Warblers harmonizing effortlessly (thanks to backing vocals provided by actual a cappella group the Tufts Beelzebubs) over Blaine’s passionate solo. It’s a space of performance and queer love and the performance of queer love and it’s most normal, flawless thing in the world, a point driven home by shots of Kurt being nearly stunned to tears amidst a tableau of is teenage dream coming true.

This illusion is, of course, short lived. and Kurt does not last long at Dalton (he doesn’t even make it the full episode). Before he and Blaine eventually marry several years later, they will break up, cheat, fight. Blaine briefly dates the very tormentor whose taunting drove Kurt to Dalton in the first place. The show has the wherewithal to play into this temporality; two seasons later, Blaine reprises “Teenage Dream” as a somber solo after he cheats. Of course the dream is short-lived; it was always going to be, as is the nature of dreams. The temporality doesn’t negate the beauty of the moment, however: rather, it heightens it, the serenity and exhilaration all the more delicious in its rarity.

Be my teenage dream. Fall in love with me with the ease and fervor of someone who doesn’t know what kind of work goes into love, what kind of heartbreak lies on the other side, just for tonight. The most natural thing in the world.

Rewatching Glee multiple times throughout the last two has enabled me to do an embarrassing amount of inner child work. I’ve done a great deal of growing since I was the teenager obsessed with Glee and afraid of myself, but that sort of growth is not complete without allowing yourself to access the things you were denied.

Though I have not always known what I wanted love to look like, I had an inkling of what I wanted it to feel like—I love music, so I wanted it to feel like a love song, all of the glitz and glamour and grandiosity and intimacy and also the ever-present impermanence mingled into the abundant possibility. I could imagine someone impossible—Blaine Anderson, my best friend, a faceless Anybody—serenading to and being serenaded by me and briefly access the sensation of a dreamy love to which I so nebulously aspired.

I’ve passed a large part of the last year falling in love so naturally and imperceptibly I didn’t realize it was happening. A smirk here, butterflies there, a feeling of serenity sitting in the deepest pits of my stomach every so often that are just a smidge too big to comfortable interrogate for more than a moment. The only clue? An hours-long playlist called “smitten” I’d been building here and there month over month while talking with the twitter mutual who would later become my girlfriend, the layer between myself and the performers providing an adequate barrier between myself and my confusing swirl of emotions. I did not process what was driving this at first—I just happen to love a lot of love songs, and they happen to get stuck in my head after I spent time with her—until a week before our first date (which, in a pseudo-adolescent way, we both refused to believe was a date), the Warblers’ rendition of “Teenage Dream” came on shuffle, and it felt like I’d been absolutely stunned in place, electrified. I listened to it seven more times, pacing around my empty apartment.

My beloved knows I’m afraid of the mysteries of love and the complexity it entails, knows this is my first relationship—long past my teenage years—and it doesn’t scare her off. She takes it as a challenge to love me better than I’ve ever dreamed possible. She consistently succeeds.

During our first extended date months later (a weekend hanging out in my apartment), she gathers me into her arms on the couch, looks into my eyes for an eternal moment, and begins to quietly, sillily sing “Teenage Dream” to me. I join in, my terrible voice doing the opposite of harmonizing with her much better vocals, until our selection song ends and we dissolve into a puddle of giggles and tender hugs. It’s a small moment, one in a sequence of many off-the-cuff serenades she’s gifted to me, but to me it’s the mundanity of what would have been a show stopping moment in my adolescent musings that is transcendent—the way it happens and then it ends and we’re still here. Love with the ease of a teenage dream. The most natural thing in the world.

Moira McAvoy lives, writes, and tweets in Washington DC. McAvoy has served on the editorial staff of NANO Fiction, The Rappahannock Review, and Bad For You; work can be found in The Rumpus, Storyscape, The Financial Diet, wig-wag, and others. Glee should never be rebooted.

Here We Are Now Megan Culhane Galbraith on Tori Amos’ “Smells Like Teen Spirit”

Mick Foley had just quit a six-figure gig with World Championship Wrestling for a job with the International Wrestling Association. The style of wrestling was called “deathmatch” for its heavy emphasis on wild behavior, “use of barbed wire, fire, thumbtacks, and blood.” Foley was trying to psych himself up to enter the ring for his final match in Honjo, Japan. He was terrified, he said, so he decided to listen to some music.

“I took out my battered Sony Walkman …” wrote the WWE Hall-of-Famer in a piece for Slate in 2010. “Finding solitude in a far corner of the frigid backstage area, I saw a cloud of my own breath as I pressed the play button. ‘Snow can wait, I forgot my mittens/ Wipe my nose, get my new boots on.’

“‘When you gonna make up your mind?’ Tori Amos asked me inside that frigid dressing room. ‘When you gonna love you as much as I do?’

“And then I realize I’m going to be all right (sic),” he wrote.

Amos’s song, “Winter,” “appealed to the sacred part” of him, he said.

Foley’s wrestling personas included a brawler named Cactus Jack, a hippie named Dude Love, and a masochist named Mankind among others. He earned the nickname “The Hardcore Legend” because of his ability to take and inflict physical punishment. Professional wrestling is a sport soaked in testosterone that’s all about persona and entertainment value: profits for WWE events quadrupled during the pandemic. So I was interested to find out that someone so decidedly cis/hetero/male was not just a fan, but a Tori Amos devotee. Foley had been introduced to Amos’ music by another pro wrestler, Maxx Payne.

“I can still remember the first time I heard Tori Amos,” Foley said.

*

Anyone who has seen a Tori show or listened to her songs can attest to the undeniable power of her voice to transform. She hypnotizes her audiences. She says her body is a conduit that channels the music. She calls her beloved Bösendorder piano “Black Beauty.” She calls on her “muses” to help her write and sing. Many times she straddles her piano bench to play two pianos at once. Her entire body is an instrument that merges sexuality and spirituality. When she looks directly at the audience, she’s neither breaking the fourth wall nor challenging us … she’s gazing inside our collective souls.

Amos is a prodigy and a polymath; a fairy and a goddess. She is a warrior, a mother, a lover, an oracle, and a survivor.

*

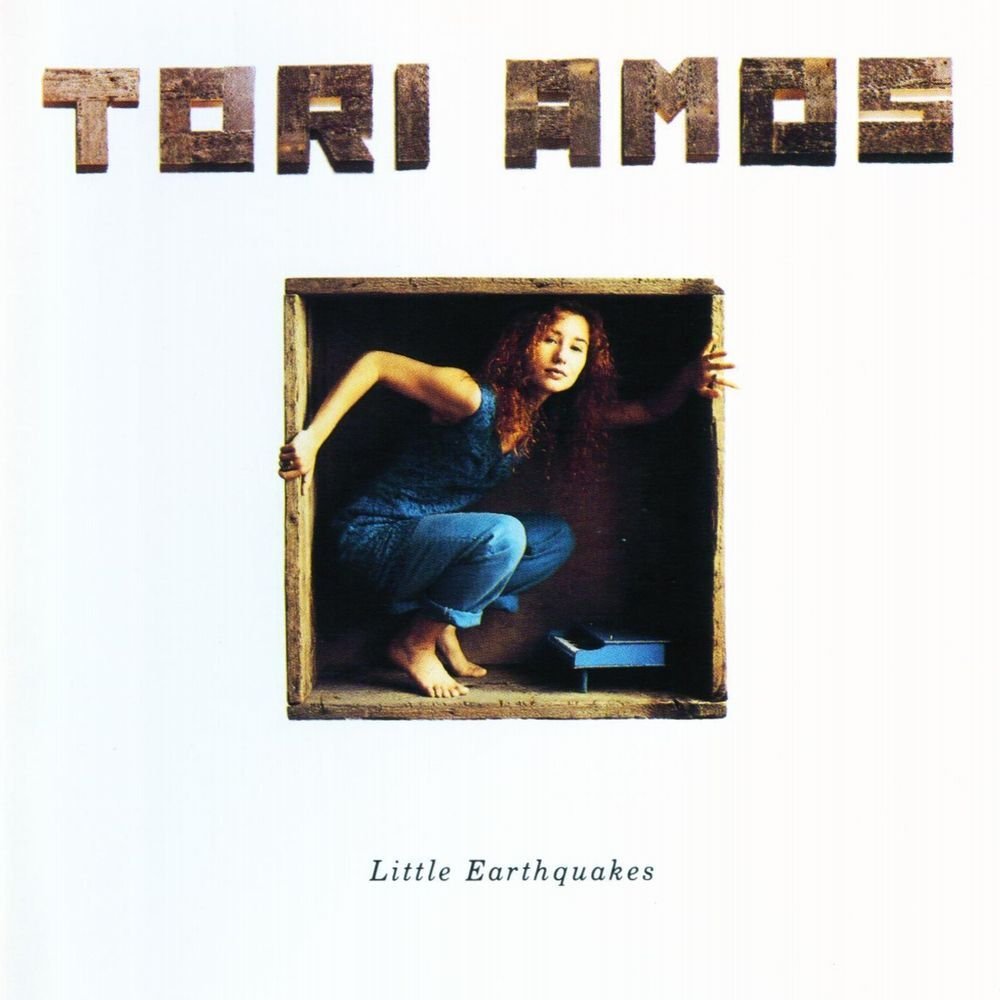

Kurt Cobain and Tori Amos had their musical breakthroughs at around the same time, but their rise, their success, and their survival were wholly different, in part, due to their gender.

Nirvana’s album, Nevermind, and Amos’ solo debut, Little Earthquakes, were released in close proximity: Nirvana’s to great fanfare in the U.S. in 1991. Nevermind was a loud, thrashing, in-your-face, album full of masculine energy, angst, and rage. The single, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, topped Billboard’s Alternative Songs chart and peaked at No. 6 on Billboard’s Hot 100. “Teen Spirit” rocketed Cobain and Nirvana to mainstream music artists nearly overnight. Three years later he would be dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

Little Earthquakes was well-received when it was released rather quietly in the UK four months later. By contrast, Amos’ album was political, personal, and defiant. Behind her piano, with a voice clear as a bell, she gave voice to millions of women–many of them Gen-Xers like me—who felt they had none. Women, like me, who had been raped before there were reporting services or formalized systems to help; who felt silenced, gaslit, desperate and alone in their experience. Here, finally, was a muse who saw through the patriarchy and was calling bullshit. Amos was someone who demanded to be listened to.

Tucked away on the B-side of her single “Winter” was Amos’ cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” As it is in a patriarchal world, those who yell the loudest are the ones who get the most attention, so when Amos released her quiet, tender cover of “Teen Spirit” it’s whispery power felt like a secret. She’d taken a shreddy grunge song about apathy, anger, and rage, and stripped it down to its acoustic parts. She slowed the song down so much that the lyrics became recognizable. Her voice channeled an unseen alchemical power that tapped the sacred part in all of us, and turned the rage and toxic masculinity against itself.

Out of her throat—reshaped through the lens of the divine feminine—came a vulnerable lullaby the world didn’t know it needed.

*

Amos’ musical path was bumpy, but it was one that she cut on her own terms. While making Little Earthquakes, she had to defend herself against music industry executives who were pushing to package her as the stereotypical “pretty girl and her guitar”; a container she refused. The first version of Earthquakes was rejected; the male Atlantic execs didn’t like the ‘girl at her piano’ optics—Elton John and Billy Joel were the piano men of the time, not women. Former Atlantic CEO Doug Morris suggested stripping her of her piano altogether. Then, they took issue with the subject matter of her songs which included rape, feminism, religion, vulnerability, and palpable woundedness. Amos resisted, persisted, and won. She kept her piano and the integrity of her voice at a time the world needed to hear it. What those execs couldn’t predict was how fiercely her songs connected with an audience of mostly women, who had been silenced all these years.

Thirty years later, “Earthquakes” is considered to be one of the best albums and Amos one of the most influential artists of all time. She just released her 17th album, Ocean to Ocean, launched a world tour, and has written a NYTimes bestselling book, Resistance. Her cult status keeps her on the edge of the mainstream, a place that seems just right for an eccentric badass who refuses to be cornered or commodified. She gives voice to the things many don’t want to talk about.

“… for straight men, I’m too raw,” Amos said in a 2015 interview with The Guardian, “... the emotional thing, the things you don’t want to talk about—that’s what goes on at my shows, [straight men are] tortured by what goes on.”

*

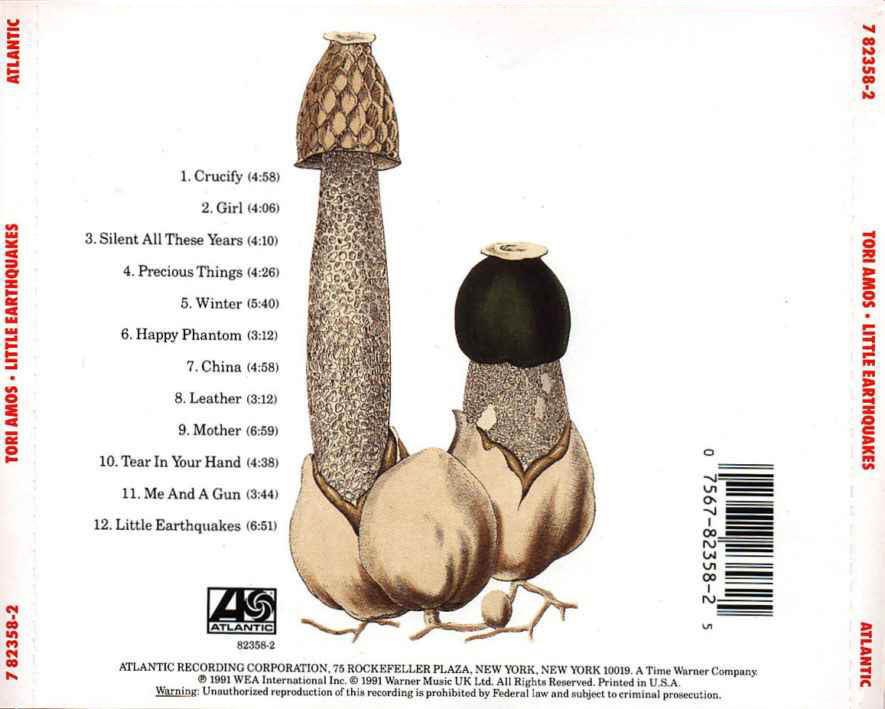

I remember the cover art of Little Earthquakes. Here was a fiery-haired, barefoot Amos, all arms and legs, clad in denim and climbing out of a literal box. Beneath her feet was a blue toy piano. It was confronting and comforting. She was looking straight into our eyes; challenging the music industry to just try to keep her in that box. On the flip side of the album were illustrations of two mushrooms that looked like cocks—one was tall and skinny with a morel-like tip that resembled the Veiled Lady Mushroom (Phallus Indusiatus) without the veil; the other was a stubby chode with a blackened head. I remember feeling like she was flipping off the music industry and all men at once.

Amos was everything the 90s girl in me wanted to be; fierce and gentle; brave and tender; vulnerable and raw; self-aware, and a survivor. Like many of my girlfriends, however, I was content ripping myself to pieces.

I was 26 in 1992, working in sports information, a profession dominated by men. I managed press boxes in which I was sometimes the only woman present; I’d been told by coaches that I couldn’t travel on the team bus; I’d been banned from locker rooms; I’d been told to apologize to my male field spotter who stomped out on me mid-football game when I was typing the play-by-play on an IBM Selectric because he thought my mutterings—“stupid thing; stop”—were about him when I’d simply been angry that someone had fucked up the indents on the manual typewriter. Once, when I’d dyed my hair bright red (inspired by Tori), a coach asked me “does the carpet match the drapes?”

The early 90s was a time pre-internet and social media; before Amazon or streaming music or video. Our phones were attached to the wall (with cords!); we watched Beverly Hills 90210, and rented movies for our Video Cassette Recorders (VCR.) The only home delivery music we had was via USPS via Parade Magazine ads boasting “Get 12 cassettes or 8 CDs for a penny from Columbia House,” which is exactly how I received my first Tori album. By then I was listening almost exclusively to women singers.

Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was all over the radio which meant athletes were playing the song in locker rooms and on the field to get themselves psyched up for games. What I liked most about the song was the modulation between whisper and scream, it felt like Cobain was delivering a dangerous message; bringing us in real close before shredding his vocal cords yelling the chorus, ``HERE WE ARE NOW, ENTERTAIN US.” The technique reminded me of a game I’d fallen for a few times when I was younger and at sleepaway camp. I’d had frenemies who’d pretend they had a secret to tell me. When I’d lean in—ready to be accepted, ready to receive their precious secret—they’d cup their hand to my ear and scream something destructive and mean.

Cornflake girls can be vicious, with their fake smiles, dagger stares, and mean-girl cliques. Teen Spirit boys can mask their sensitivity with rage, sullenness, physical violence, yelling, and inappropriate comments.

Both are signs of teens struggling to express their vulnerability.

*

Amos said she first heard “Teen Spirit” via an MTV video while on tour. After she heard it she turned off the TV and sat in silence as her beloved Bösendorfer piano beckoned.

“... the piano kind of just showed herself to me,” Amos said in an interview with Stereogum … "And she said to me, ‘Listen, this song is so powerful and so strong that it can hold a different read. You really need to partner with me and trust me on this.’ And I thought, I don’t know about that, because this version is the thing that’s blowing me away. And she said, ‘... go into the vulnerability of it.' "

Cobain’s original version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is the product of so much projection and speculation that we’ll perhaps never know the true meaning of a song he called “both meaningful and meaningless.”

“Teen Spirit”—a song that became an unlikely analogue to teen angst, apathy, and rage—was written as an inadvertent response to a joke about smelling like a girl.

Cobain’s friend Kathleen Hanna of the band Bikini Kill had written “Kurt Smells like Teen Spirit,” as a joke after she and Cobain’s then girlfriend discovered a deodorant by that name at the store. Not knowing its origins, Cobain interpreted the phrase as a radical call to action.

Teen Spirit (TM) was the most popular deodorant brand marketed to girls in the early 90s. The antiperspirant had scents like Pink Crush, Pop Star, and Romantic Rose. These weren’t so much scents as fucked-up archetypes of how corporate America thought girls should be.

“Teen Spirit” the song was packaged, marketed, and sold to us Gen-X latchkey teens as the forgone conclusion of how we were supposed to ‘be.’ Did it work? Did we feel stupid and contagious? Who among my generation remembers packing their own lunches and getting their siblings off to school, then coming home to an empty house in time to watch General Hospital, program the VCR, lie about doing our homework, and get dinner started?

I remember my Mom coming home bone tired. I don’t remember anyone asking me how I felt about anything. I did a lot of staring out the window and skipping school. I worked two after-school jobs, sometimes three. We didn’t have cable—just four channels and UHF—no MTV. Our means of communicating with the outside world was by corded telephones stuck to the wall (mine was mustard yellow), or by passing handwritten notes in class. Cell phones, iPods, and laptops were at least a decade away or more from regular use. We took typing class on IBM Selectric typewriters. We bought our Walkmans at Radio Shack. We were so fucking bored. Out of economic necessity we were left to entertain ourselves.

Today, we Gen-Xers are considered a largely forgotten generation, the ones sandwiched quietly between the Boomers and the Millennials. We’re considered the glue that holds everyone’s shit together. At the time we were also a captive audience to sell to because our parents were never around.

Can you imagine what Cobain must have felt like having written a song so full of paradoxes like “Smells Like Teen Spirit?” A song that gave MTV “a whole new generation to sell to,” according to Amy Finnerty, then director of MTV’s music programming.

Can you imagine living with the notion you’d sold-out a generation?

Amos talks about fame as the great seducer; about the tightrope artists walk trying to make art in a world where art is recognized only if it makes money, and about asking herself when she was gonna make up her mind.

“It was years of buying into the idea that to be successful and pay my bills as a musician, I had to fit into a certain slot, a commercial slot,” she said in a recent interview in The New Yorker. “ . . . I had to get through the shame and the blame and the embarrassment, just being disgusted with myself for betraying the dream I had, and asking myself, ‘How do you go from prodigy to bimbo?’ Those scabs being ripped off—they didn’t just sting a little bit. I had to come finally to terms with what kind of writer I was, and what kind of writer I wasn’t.”

*

The power of Amos’ cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is in its intimacy, intensity, and relentless vulnerability. While Cobain’s original yelled about and at the feelings, Amos’ version leaned right into them reminding us that vulnerability is power and that expressing sadness need not be harsh, abrasive, or loud. When she sings “Here we are now . . .” it’s a growl/purr. Her audible breathing becomes part of the song.

Her shows have been called “planned enchantments.” Many times you can hear a pin drop while she’s singing. She commands our full attention because we have hers. She reminds us that the greatest gift is to listen. By resisting commodification she’s given voice to a generation of fans who refuse to be sold to.

“The relationship with the fans is the area where the least bullshit goes on,” writes Amos in her book Piece by Piece: A Portrait of the Artist, Her Thoughts and Conversations. There’s an agreement. They want this person that will be someone they have a relationship with. I can do that. I know what they need from her. I’ve got no problem with that.

“The key question is, Can you listen?” she continues. “You really learn from people’s stories and can see, Wow these are people relating to these songs. So, whatever the record companies are telling me these people want to hear, I have to wonder what it is based on? Some nefarious demographic exercise that suits and bean counters calculate by monitoring what products people buy at Walgreen’s? Not relevant to my crowd.”

Amos learned about Cobain’s suicide while on tour in Ireland. Her audience begged her to play her version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

“... I can’t remember another feeling except the day John Lennon died,” she said. “And so by the time I got to Ireland, I didn’t know if I was going to play the song or not. The Irish said, “You have to play it because we need to grieve. Please, you have to play it.” So I paired [Don McLean’s] “American Pie” and then played “Teen Spirit.” And within a few seconds, once I started “Teen Spirit,” I started to hear this crooning. And there were thousands of Irish people singing “Teen Spirit,” the version that I did, in perfect pitch. I’m sure you’ve heard of the Irish, “the keening,” when they grieve. I haven’t felt anything like that before [or] since with an audience.”

In his book, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, Lewis Hyde writes “... a work of art is a gift, not a commodity. Or, to state the modern case with more precision, that works of art exist simultaneously in two “economies,” a market economy and a gift economy, Only one of these is essential…”

Amos’ cover is an anthem of empowerment; a gift in its purest form.

Amos is a Cassandra we need to listen to.

*

Little Earthquakes and Nevermind are now both adults. Earthquakes celebrates its 30th anniversary and Nevermind is the slightly older brother at 31. We Gen-Xers are adults now too; some of us are raising our own children during one of the most unrelenting and stressful times the world has ever known. We’re with our kids 24/7. They can’t escape us, we can’t escape them, we can’t escape the world.

This generation has all the devices we didn’t have when we were kids: iPads, iPhones, laptops, gaming systems, Netflix, Hulu, HBOMax. Boxes of stuff can be delivered to our doors (by drone if necessary.) Amazon is a commodity not a rainforest. Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat are slowly draining our kids' brains; they’re the commodity. They’re the ones being sold. Instead of bringing us closer together, social media is showing our kids how to be lonelier and lonelier. All we can do as parents it seems, is sit around and binge watch . . . because we’re lonely too. Perhaps we escape into boxes of wine, or weed, or sourdough starters, or food; or perhaps we don’t have the privilege of escape at all.

Guns factor prominently in both singer’s lives. The police had confiscated Cobain’s guns twice before he shot himself with a shotgun that had been purchased for him by a friend. Even his tragic death was packaged like a product. His handwritten suicide letter has been commodified and spread across social media. T-shirts were marketed and sold with his letter printed on them. Can you imagine having your posthumous pain being publicly marketed and displayed? Cobain became an unwitting brand ambassador for suicide.

In a 2014 interview in The Guardian, Lana Del Rey said, “I wish I was dead already,” referencing Cobain and Amy Winehouse who had both killed themselves. Frances Bean Cobain, Kurt’s daughter, tweeted:

@LanaDelRey the death of young musicians isn't something to romanticize ... I'll never know my father because he died young & it becomes a desirable feat because ppl like u think it's "cool" ... Well, it's f****** not. Embrace life, because u only get one life. The ppl u mentioned wasted that life.Don't be 1 of those ppl.

@LanaDelRey I'll never know my father because he died young & it becomes a desirable feat because ppl like u think it's "cool"(cont)

— Frances Bean Cobain (@alka_seltzer666) June 23, 2014

She was just two years old when her father shot himself. Like Amos, Cobain’s daughter also uses her voice to encourage healing. Frances Bean Cobain controls the rights to her father’s name and image. At an exhibition “Growing up Kurt Cobain” in Ireland in 2018 she said she uses the words, peace, love, empathy often—words her father used in his suicide letter— ”... because I want to reclaim the peace, love, empathy thing as something that's meant for health and for compassion and for true peace, love, and empathy.”

It gives me chills to hear his version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” now because in hindsight the lyrics sound as if Cobain is reaching out, wanting to begin a conversation about his pain.

“Hello, Hello, Hello …”

*

A January 4 piece in The New York Times titled “No Way to Grow Up” detailed four separate government advisories citing suicide among children and teens as the biggest growing crisis in America with black children nearly twice as likely to die by suicide than white children.

The Surgeon General’s advisory said:

During the pandemic, young people also experienced other challenges that may have affected their mental and emotional wellbeing: the national reckoning over the deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police officers, including the murder of George Floyd; COVID-related violence against Asian Americans; gun violence; an increasingly polarized political dialogue; growing concerns about climate change; and emotionally-charged misinformation… It would be a tragedy if we beat back one public health crisis only to allow another to grow in its place …

“It’s chaos,” Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union, told Dana. “The No. 1 thing that parents and families are crying out for is stability.”

Amos has said she “writes songs to survive.” In “Me and a Gun,” the gun stands in for the knife Amos’ rapist carried. By being public in her grieving, Amos holds space for us to heal together. It’s no surprise that the phrase, “Tori Amos saved my life,” is ubiquitous among her fans. Her songs renewed her power at a time she felt she had none.

“'Winter' gave me self worth, and 'Leather,' and 'Happy' and 'Little Earthquakes...' but ''Me and a Gun'' gave me back my ability to have sex again and not feel like I'm soiled for the rest of my life—or that I'm scarred,” said Amos.

In 1994 Amos co-founded RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, and now serves as its national spokeperson. A powerful support network for survivors of rape, abuse, and incest, RAINN operates the National Sexual Assault Hotlines (800.656.HOPE and www.rainn.org) in partnership with more than 1,100 local rape crisis centers across the country. The hotlines have helped more than 1.5 million people since 1994. RAINN also carries out programs to prevent sexual violence, help victims and ensure that rapists are brought to justice. It was named one of “America’s 100 Best Charities” by Worth magazine. I wish such an organization existed when I was raped in college, but in 1986 I didn’t have anywhere to turn except inward. I didn’t know anyone else had gone through what I had so I dissociated … until I recognized myself in the lyrics of “Cornflake Girl:” “. . . this is not really happening … you bet your life it is.”

*

Back in that locker room in Honjo Japan, Mick Foley understood the power of one voice to uplift many. He seems an unlikely fan doesn’t he? I mean the WWE isn’t known for its quiet, sensitive characters, but it sure is pure entertainment.

After being introduced to Amos’ music, Foley became a huge fan so when they met at a Comic Con and she asked him to join the board at RAINN, he became an immediate ally.

Amos, Mick Foley, and Collette Foley

During his #10forRAINN Twitter Campaign, Foley matched gifts of $10,000 to RAINN and logged nearly 600 hours as a hotline volunteer talking with survivors. He even offered to mow anyone's lawn who donated at least $5,000 to the organization. In addition, he auctioned off his Cactus Jack lace-up "leopard skin" boots (embedded with 149 thumbtacks from his Impact match with Ric Flair); and the white shirt he wore as Mankind during his "Hell in a Cell" match.

Amos continues to shape the conversation about resistance and healing. Her cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” reinforces that we need to listen harder to those, like Cobain, who are trying to communicate the “sacred part” of themselves to a world that isn’t ready to listen.

“If you're going to document life and you're going to be accurate about it, sometimes you're called to deal with some tough subjects,” Amos said in a PBS interview. “So we have to find ways to travel there and then ways hopefully to uplift somebody out of that.”

Here we are now.

Megan Culhane Galbraith is a raisin girl who’s gone to the other side. She’s the author of The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book (Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University Press) and the Associate Director of the Bennington Writing Seminars. A writer and visual artist, you can find her work at www.megangalbraith.com or find her on Twitter @megangalbraith or on Insta @m.galbraith