round 1

(5) Lemonheads, “mrs. robinson”

SENT HOME

(12) the stooges, “louie louie”

207-176

AND WILL PLAY ON IN THE SECOND ROUND

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/3.

ryan carter on the lemonheads’ “mrs. robinson”

The Lemonheads’ cover of “Mrs. Robinson” may be the catchiest and upbeat song about alcoholism and being institutionalized.

“Mrs. Robinson” contains a story. In short, it goes like this:

You’re an alcoholic, Mrs. Robinson, and we all know it

For your own good you’re going to an institution

Yeah, you’re stuck there

Do some praying, perhaps. Trust in the rare appearance of a hero like Joe DiMaggio to reassure you

Hey, hey, hey

The original 1968 version is a little bit slower, a little less loud, and it feels more sympathetic to its character. In the hands of The Lemonheads, which is pretty much Evan Dando, it’s a power pop gem.

Dando was paid to give it a substantial facelift. (That’s a sore spot for purists: more below.) It’s fast, it’s upbeat, it contains “do-do do-do’s” as well as a coo-coo kuchoo. There’s a bubbling bass line. Joe DiMaggio is there. What’s not to like?

The song was and is quite popular. When Simon & Garfunkel released it in 1968, it hit #1. The strong tie-in to the movie “The Graduate” didn’t hurt.

With The Lemonheads in 1992 it was also a commercial hit, though the circumstances were less than artistically ideal. Dando tells the story in his own words:

“We were paid $10,000 to do a cover of it for the person who acquired the rights to sell the videocassette, and we did the song because we loved the movie…. We literally recorded it in two hours. I learned it from a book, we made up three parts and press record, and we got it on the first time we ever played it all the way through.”

The song was tacked on to the end of their breakout album It’s A Shame About Ray. The label released it as a single without the band’s approval, in Dando’s telling.

He’s since made his peace with the experience. The song was later featured in the Martin Scorcese 2013 film The Wolf of Wall Street, which has improved Dando’s view.

Regarding the decision to record the song and losing some esteem in the eyes of purists for the circumstances, these days Dando asks, “how serious are you gonna get about it, really?” At the very least, doing the recording “was fun, certainly.”

What I like about the cover is that the fun the band is having is apparent. Clearly they were playing very well with each other, and this perfect little recording happened.

Dando has always taken covers somewhat seriously. “I was always very careful about my covers, and I was always proud of the songs I covered,” he says in a 2012 interview. His cover of the “Frank Mills,” from Hair, on It’s A Shame About Ray is remarkable. In 2009 and 2019 The Lemonheads released albums solely of covers.

Yet this is also the man who posed with Bjork, he wearing a model-serious expression and a pretty print dress, she wearing most of a boxy men’s suit. In an appearance on Top of the Pops in 1992, he channels Morrissey for the Joe DiMaggio verse of Mrs. Robinson. It’s pretty funny. Purists may not delight in it, and Morrissey himself probably wouldn’t, either. As Dando might say, how seriously do you really want to take all of this? Have fun with it.

Ryan Carter is a research librarian. Originally from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, he now lives in Fort Collins, Colorado.

It’ll all be over soon: joe bonomo on the stooges’ “louie louie”

This is what the end sounds like.

First, a beginning: James Osterberg, Jr. was born on April 21, 1947 in Muskegon, Michigan, a small town on the Lake Michigan shore. He grew up with his parents in a trailer park in Ypsilanti, just west of Detroit. He dug rock and roll, started playing drums when he was around eleven, made a lot of noise in that trailer. In school he was, by the looks of things, a pretty average teenager. Clean cut, cleanly dressed. Debate Team. “Most Likely to Succeed.” Yet things were always seething below the surface.

Here’s Osterberg in a poignant scene from Gimme Danger, Jim Jarmusch’s 2016 documentary about The Stooges. He’s recalling a time when some kids from school paid a visit to his family’s trailer. “They were a group of the slightly more popular, slightly more physically aggressive guys in my class,” he said. “And there were about four or five of them at the time. I'd been to one or two of their homes, I used to eat french fries with them across the street from school.”

So one of them had a car his daddy'd given him. They came out, they did three things. One of them said, “Yeah, look, his dad drives a Cadillac and he lives in a trailer. The car's bigger than his house!” A few of them got together: “Let's see if it shakes!” And they started pushing it and trying to shake the trailer on its foundations—which it would not, but you did feel, you could feel it. Yeah, I wanted to be friends with these guys, and I admired certain things about them. One of them jumped in the bathtub and made some sort of remark about the size of the bathroom.

He adds: “And ever since I've been out to get ‘em. Ever since. You know? I'll bury those guys.”

By the early 1960s The Kingsmen (Lynn Easton, Jack Ely, Mike Mitchell, Bob Nordby, and Don Gallucci) had been banging around the Pacific Northwest for a half a decade, and they were itching to cut a record. They dug Rockin’ Robin Roberts’s cover of a Richard Berry 1957 b-side, an R&B/Cha-Cha number called “Louie Louie,” marveling in some club they were visiting in Seaside, Oregon one long night as the song came roaring from a jukebox. They didn’t know what the hell the song was about and they couldn’t understand the words, but they knew this: the tune got whoever was listening up and moving. Other bands were picking up on the number, and it was becoming wildly popular on the local scene. Inevitably, bands were going to try to nail a version of “Louie Louie” and put it out as a record, and soon.

The Kingsmen wanted in. On April 6, 1963 they met at ten in the morning at Northwest Recorders, a small recording studio in Portland. Because “Louie Louie” never failed to rouse and move a crowd with its three-chord stomp, its super power, its stumbling charm, the night before the session The Kingsmen had played a delirious ninety-minute version of the song at a gig. The band arrived at the studio wearing an uneasy blend of exhaustion, nerves, and ambition. Like many local bands, they’d rearranged the song after Roberts’s version, clumsily de-Latinizing it in the garage rock tradition and retaining Roberts’s unhinged ok let’s give it to ‘em right now! launch to the guitar solo. Their manager Ken Chase was nominally producing.

Dave Marsh, in his essential Louie Louie—and I’ve got to supply the book’s epic subtitle here, The History and Mythology of the World's Most Famous Rock'n'Roll song; Including the Full Details of Its Torture and Persecution at the Hands of The Kingsmen, J. Edgar Hoover's F.B.I., and a Cast of Millions; and Introducing, for the First Time Anywhere, the Actual Dirty Lyrics—picks up the story: “They went inside and set up their gear as quickly as possible—studio time cost money, and the clock started running when they walked through the door. But then there wasn’t that much equipment to set up and Northwest Recorders, while the best facility in Portland, was pretty primitive itself. The band moved a large backdrop curtain and rolled up a rug. Within a half hour, engineer [Bob] Lindahl began placing the microphones.” As Marsh notes, this became an issue. Rather than on a stand or in a vocal booth, “Northwest Recorders’ vocal mike hung from a large boom stand, and it was so unwieldy it remained well overhead. Jack Ely was forced to stand on tiptoe.” Other reasons for Ely’s slurred delivery? “He wore braces on his teeth, and the “Louie” marathon had been cord-crunching.”

After a false start, Chase pivoted and asked his boys for a simple run-through of the number so that Lindahl could check and set the sound levels. Marsh: “Easton counted the song off and again kicked into duh duh duh. duh duh. Ely squalled upward at the mike as hard as he could. The band was nervous; this may have been a rinky-dink setup but it was their Shot.”

Ely yawped like Donald Duck in a rage on “Okay, let's give it to ’em, right now!” The others’ nerves showed, too: Just before the vocal came back in, Lynn Easton clacked his sticks together and cussed, “Fuck!” Although Lynn was off-mike, he said it loud enough to register slightly on the tape, and never quite recovered the beat, stuttering and stumbling throughout the rest of the take. When they got to the guitar break, Mike Mitchell fumbled his way through his Rich Dangel-inspired solo as if he'd never heard of the song before.

Ely blew his vocal entrance on the last verse. The drums were sloppy. The band hated it and wanted to re-record it. Chase loved it and wanted it on the radio. “Louie Louie” was released as a single on Jerden in June of 1963 and then reissued on Wand in October of 1963. Soon the universe would one-two-three, one-two on its axis.

First came an FBI investigation into the reputedly dirty lyrics (final verdict: “unintelligible at any speed”), then the innumerable obligatory garage band covers. Then a kind of cultural obsolescence, then John Belushi and Animal House, then a retro revival, and finally (?) Irony. (Dave Marsh lists over one hundred and fifty different recorded versions of the song in an appendix in Louie Louie; the list is ongoing.) By the mid-60s, a few Detroit-area bands had gotten their hands on the song and, to the growing concern of local officials, would mildly dirty-up the lyrics onstage at teen dances. Osterberg’s first band the Iguanas, for which he grinningly banged the drums and which would be the origin of his lifelong nickname “Iggy,” played ramshackle versions of the song. Osterberg interpreted The Kingsmen’s interpretation of Roberts’ interpretation of Berry’s sailor’s glee at returning to his Jamaican girl by turning it into Midwest smut, making far more explicit the bawdiness rumored to be lurking in the swamp of Ely’s slurred vocals on The Kingsmen version.

By the time Jim Osterberg adopted his stage name and persona Iggy Pop and his band The Stooges got around to recording “Louie Louie” in 1972, they had two crucial, ground-breaking rock and roll albums behind them, their self-titled debut (1969) and Fun House (1970, produced by Kingsmen organist Don Gallucci), each of which stiffed commercially. Their shows were legendary—Iggy prowling the stage and hurtling himself into the dark mayhem of the crowd, the Asheton brothers, Ron on guitar and Scott on drums, stripping an already minimal groove to its bones, Scott pummeling his kit or riding steady, glowering, while Ron fuzz-riffed, wah-wah’ed, and slashed on guitar. Their record label Elektra eventually gave up on them, unhappy with their poor sales and anxious about the band’s active mutation into a druggy muddle. Bass player Dave Alexander was booted in 1970. After some lineup shuffling and a brief break-up, during which Iggy, under David Bowie’s generous wing, relocated to London as a Columbia Records solo artist, The Stooges reassembled with fellow Michigan-native James Williamson on guitar and Ron moving over (he’d later say “demoted”) to bass with Scott back behind the drums. This is the lineup that cut the stunningly ferocious Raw Power album in 1973.

In the studio in London in Spring of ’72, with the members’ drug use and interpersonal anarchy threatening to derail everything, The Stooges fired up “Louie Louie.” It isn’t much, really, a run through, a loosening-up job. Williamson’s riffs are loudly assertive and Scott Asheton, playing an open hi-hat, tries to inject some swing into things, but the band sounds uncharacteristically tentative, a little distracted, maybe bored. This version calls to mind the Paleolithic arrangement that The Sonics played for their 1966 cover of the song on their album Boom, Larry Parypa’s guitar a pummeling jackhammer relative to Don Gallucci’s loose-limbed organ riff. Iggy’s voice is a ragged mess. He’s half-faithful to Berry’s original lyric in the first verse, then in the second verse steps into the lewdness that he’d regularly amplify onstage—she’s not the kind of girl he’d bring home; it’s a fuck-and-go situation; in front of a rabid crowd he added more indecorous details—but the thing’s finished in a couple minutes, and never really transcends its workmanlike vibe. Based on this lone studio recording, it’s safe to assume that the song came alive onstage for the band, Iggy reveling in just how far he could push the filth and shock a crowd inside an innocently beery frat-rock standard.

If all else fails, do “Louie Louie,” right? That’s what you learn playing in a fraternity band for five years. Play “Louie Louie” and it will always get you outta anything. —Iggy Pop

The knocked-out praise that The Stooges’ first three albums now receive obscures the dire situation that the band was in by early 1974. Addictions, commercial irrelevance, and inter-personal animosities were gnawing at the band, dragging them from any mainstream connection they might’ve secured with rock fans and igniting their increasingly sporadic shows with dangerous consequences. Always an audience-baiter (“I'll bury those guys”), always a self-harming provocateur, Iggy was by ’74 a genuine danger to himself, smack-addicted, ‘lude-lost, alcohol-abusing, willingly, loudly courting violence on and off the stage. Some of it was indeed “an act”—The Stooges’ fan base expected and in some ways demanded it—but much of it was Osterberg’s inner turmoil in action. “It was an act for a long time,” Ron Asheton acknowledged to Paul Trynka in Iggy Pop: Open Up and Bleed, “sincere, wholesome emotions that made him be Iggy. Then it spilled over. To where he could not separate the performance from his real life.” (In the mid-1970s, Iggy would enter a Los Angeles hospital for treatment for heroin withdrawal, and intense psychiatric evaluation. He left relatively healthy and more committed to his career.)

The events between February 4 and 9, 1974 have assumed mythic proportions in Stooges history. This frigid Michigan week saw Iggy and his band bottom out in violence, ennui, and grim comedy. As with many legendary stories handed down from participant to participant, witness to witness, fan to fan, dreamer to dreamer, the versions of these incidents have been altered down the years. “I am trying now to exaggerate the essential,” Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, “and purposely leave the obvious things vague.” The obvious things? The Stooges were all but finished when they took the stage at the Rock ‘N’ Roll Farm in Wayne on a Monday night, and Iggy was a strung-out mess. Soon after the show began, hostile patrons began throwing stuff at the stage. The essential? Iggy, wearing a floppy flowered hat, a leotard, and ballet slippers, got his clock cleaned by a biker.

Iggy and others have been sharing their versions of these iconic events for decades; unsurprisingly, the tales have grown to varying heights. After a hailstorm of eggs hit the stage, Iggy stopped the show, demanded to know who was responsible, and leapt into the crowd, wild-eyed for confrontation. “Lo and behold, the waters part and hundreds of people spread apart,” Iggy tells Anne Wehrer in his careening 1982 memoir I Want More. “And there before me, about 75 feet yon, really just standing there like man-mountain Dean, just grinning, feet squarely planted, toes out, was this ENORMOUS youth with the most, the biggest, happy smile I’ve ever seen.”

Really, it was a wonderful smile, cause he knew he was king and was about to kick my ass (I’m hoping not too badly), with long flowing red hair. He must have been 6' 5", huge shoulders, had this large plaid lumberjack shirt, this big grin. And this one arm had a knuckle glove on—a KNUCKLE GLOVE that went ALL THE WAY UP the arm, studded at the knuckles. He was carrying one of those dozen-egg cartons—his weapon. He’s clearly got his act and he’s just standing there, a hand on his hip, just leering at me, you know, and in a deep, resounding voice he says, “Hello.”

He brought Iggy down with one mammoth punch to the head.

A decade later, speaking with Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain for their oral history Please Kill Me, Iggy alters the story a bit, claiming that the guy “didn’t deck me, he couldn’t knock me down, it was real weird.” (He’d also claim that this was the guy’s “initiation for a motorcycle gang, to egg Iggy for the Scorpions!”, an assertion that, needless to say, has been uncorroborated.) The storied studded knuckle glove reappears each time that Iggy tells it, as recently as his sprawling conversations with Jeff Gold for the Stooges biography Total Chaos, published in 2016, yet Skip Gildersleeve, a fan who was at the Rock ‘N’ Roll Farm show, is quoted in Trynka’s biography remarking, “I’ve heard how the biker was supposed to be wearing studded gloves or a knuckle duster. He didn’t.” He adds dryly, “He didn’t need one.”

(Uncontested is a hysterical chain of events immediately following the gig: a woman whom Iggy had been seeing spirited him away to the safety of her house in the suburbs, where she was living with her parents; the next morning a dazed Iggy endured—and probably charmed his way through—a quiet breakfast with the girl and her mother while still clad in his ballerina outfit and slippers. Iggy, laughing to Gold: “I met her mother in the fuckin’ tutu.” Perhaps out of deference he removed his floppy hat, but nothing could’ve been done about the dried blood and welts on his sorry face. He’d bear a lifelong scar between his eyes.)

Whatever the precise events of February 4th, Iggy remained bruised but unbowed, crowing about the incident a day or so later on WABX, promoting The Stooges show at the Michigan Palace on the 9th and daring the biker and his gang to attend. “I went on the radio,” he related to McNeil and McCain, “and said, ‘The Scorpions sent this asshole down to egg me, so I say, come on down, any Scorpion, let’s have it out and see if you're man enough to deal with the fucking Stooges!’” According to Trynka, “no Scorpions seemed to show up” at the Palace, en masse anyway; in the event, The Stooges had prepared reinforcement backstage in the form of God’s Children, a biker gang associated with Detroit legend John Cole. As it turns out, Scorpions Vs. God’s Children (Featuring Iggy Pop) was averted.

But there was still plenty of violence onstage. “People were throwing stuff at us from the very beginning of the show,” Iggy told McNeil and McCain, “cameras and compacts, expensive shit, a lot of underwear—then came beer bottles and wine bottles and vegetables, stuff like that. But I had an arsenal backstage and a few throwers, so I had them all come out and whip stuff back at them.” Prowling through their setlist, The Stooges played to menace in the combative air, half-aware that this might be their last gig. The then-unreleased “Open Up and Bleed” (during the ominous start of which Iggy asks for applause from everyone “who hates The Stooges”; they oblige) and “I Got Nothing” (a.k.a., “I Got Shit”) are intense and urgent, Iggy’s harrowing, brutally honest lyrics about feeling used and wasted, about being down harder than he’d been strong, delivered in desperation. The tension between the stage and the crowd is palpable.

But the insulting “Rich Bitch” and puerile “Cock In My Pocket” (“a song that was co-written by my mother”) follow, and the despair and urgency devolve into adolescent smirking, pseudo-outrageous riffs that might’ve worked if they were funny. Reading the unruly crowd, Iggy seems to feel that his band’s time is up, in more ways than one. “Anybody with anymore ice cubes, jellybeans, grenades, eggs they want to throw at the stage, c’mon. You paid your money so you takes your choice, ya know,” bellowing hoarsely, “It’ll all be over soon!” Band introductions follow—the end is near—as Iggy anoints himself “your favorite well-mannered boy.” Responding to a sarcastic jibe from the audience, or from inside his own head, he yells into the darkness, “I am the greatest!” It’s hard to know whether the band’s endless tuning throughout all of this requires Iggy to fill time by baiting and insulting the crowd, or whether it’s the ambient soundtrack for it. He ridicules the audience for missing him with their continuous stream of eggs (“Listen, I’ve been egged by better than you!”), and narrates a new incoming hailstorm of light bulbs and plastic cups (“Oh my, we’re getting violent!”), before admonishing the audience:

I think a good song for you would be a fifty-five minute “Louie Louie.” Would you rather we just ran through our programmed set and looked real slick, or would you rather we just relaxed and did “Louie Louie”?

Without waiting for an answer, Williamson impatiently kicks off the riff that Iggy’s loved since he was a teenager, and as his band lurches into the song Iggy yells at the crowd, “I never thought it would come to this, baby!”—in disbelief or irony, it’s impossible to know in the moment. “Just want to fuck, don’t want no romance,” he had sung in “Cock In My Pocket” a few minutes before, a taste of the lewdness that would come oozing from “Louie Louie.” Iggy reaches back for his well-worn X-rated take on Richard Berry’s words, but who knows if howled references to menstruation and appeasing blow jobs, if slut-shaming, bare tits, and a black ass have any effect on the jaded crowd anymore. It’s 1974, not ’64.

Following the collapse of the song on its final, weary chord, Iggy addresses the crowd for the last time:

Thank you very much to the person who threw this glass bottle at my head. You nearly killed me, but you missed again. Keep trying next week!

The last sound on tape is a bottle landing on the stage with a crash.

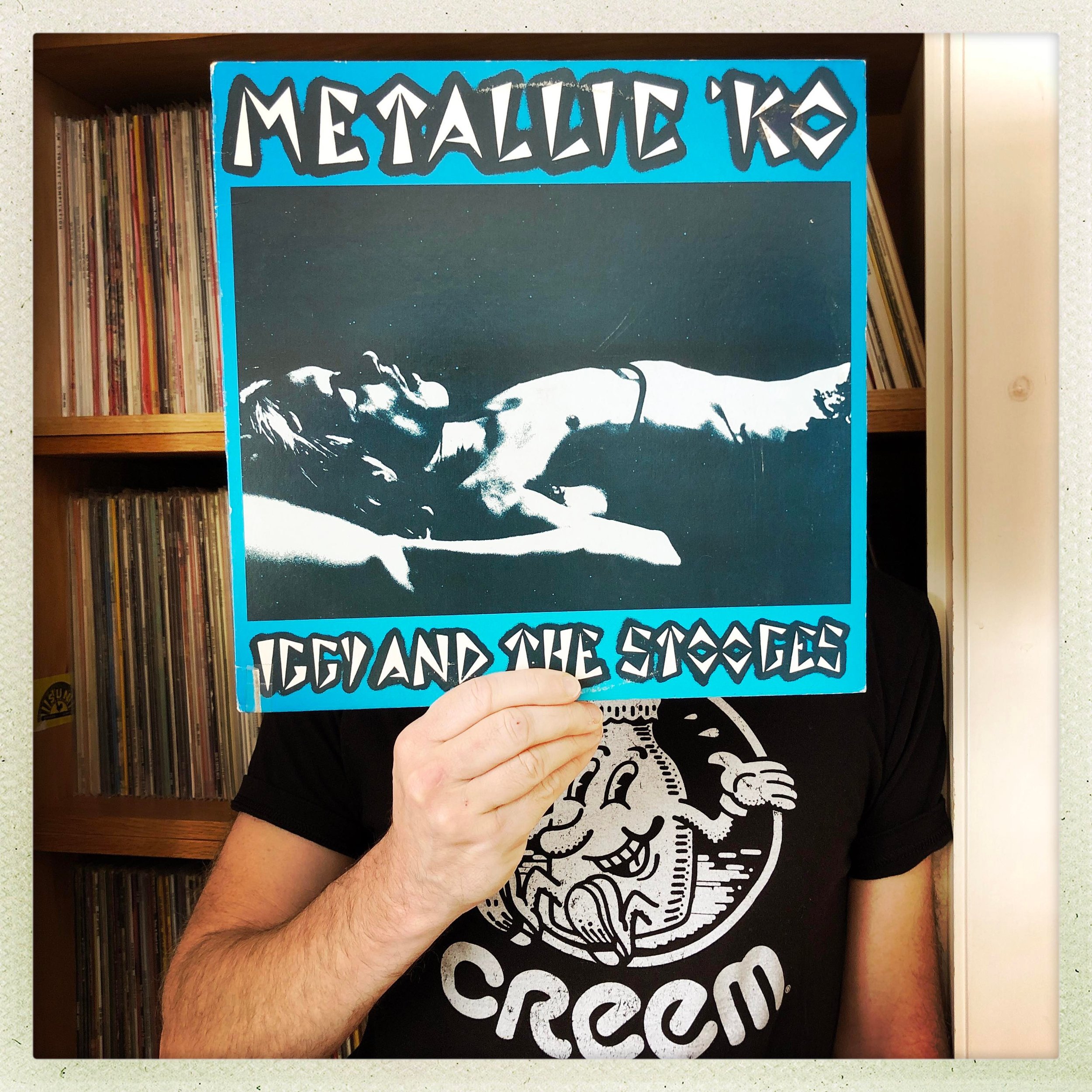

We can eavesdrop on the wretched grandeur of The Stooges’ show at the Michigan Palace because a young man in the crowd named Michael Tipton recorded the performance on reel-to-reel. Those tapes would change hands a couple of times before being released by the Paris-based Skydog label in 1976 as the infamous Metallic K.O. (coupled with tapes from a 1973 show at the same venue; the album’s been reissued in expanded versions numerous times). Following The Stooges’ implosion, this sought-after album became the stuff of legend, and would ultimately be as influential on the mid-70s U.K. and U.S. punk rock bands as The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” had been on mid-60s garage bands. The cover features a photo of Iggy from the show—you can see the top of his Danskin—allegedly knocked out cold on the stage.

“Can’t remember how I found out about [the album],” Iggy told Gold, “but the first thing was, I thought was, ‘Hey, I love the picture’.”

The Kingsmen found a home in “Louie Louie,” the decades-long durability of which probably amazed them. Some days I listen to The Stooges’ deconstruction of the song and it sounds like a bad joke, a desperate pose in the face of hostile indifference, a house of cards I could blow over. On other days their song sounds, and feels, like performance art of the highest order. On those days, what fascinates me is the movement from the mystery in Ely’s vocal to the transparency of Iggy’s, a move from wide-eyed innocence to heavy-lidded jadedness that’s nothing short of a lesson in cultural history. The Kingsmen’s song wasn’t explicitly dirty, but playground and high school hallway rumors would have none of that, and desire took over, told its story, all manner of lascivious imagery and blue phrases filling the heads of kids all over the place. (A side note: The Kingsmen’s insane “Little Latin Lupe Lu,” released in 1964, has always sounded a lot filthier to me than “Louie Louie.” Recorded “dirty” with tons of distortion at what sounds like a single-bulb basement-party, the excitable percussion and rumbling floor-toms are impossibly sexy and nearly take the song down. Shake it, shake it, Lupe. I don’t know how the thing was released sounding as unbuttoned as it does.) Iggy Pop squeezed the mystery out of “Louie Louie,” making what was kinda-sorta heard (and certainly desired) into explicit, poor man’s porn, and that aggressive, bullying move was punk as hell, if unsubtle. Iggy and The Stooges Did It Themselves. What both versions of “Louie Louie” can’t extinguish is the mystery in the music, the eternally renewing three-chord majesty, the perpetual motion machine those chords create, the primal hip shake of it all. “Louie Louie” will never end.

Of course, this wasn’t the end of The Stooges, either. Fantastically, the band reformed in the early aughts, first with Ron Asheton and then, after his death in 2009, with James Williamson on guitars, and with Minutemen/Firehose bassist Mike Watt they toured internationally to venues packed with adoring fans and awe-struck critics, and released two albums, The Weirdness (2007) and Ready To Die (2013).

Since the mid-1970s, Iggy has been shepherding a solo career through sundry sonic highs and lows, experimenting across styles, bands, and labels, eventually earning the sobriquet of “Godfather of Punk.” In 1993 he released his eleventh solo album American Caesar, a strong collection following the commercial and artistic success of 1990’s Brick By Brick (which gave him a hit with “Candy,” a duet with The B-52’s Kate Pierson). At the request of his label, Iggy hauled out “Louie Louie” one more time. He blew off the dust and whatever else was sticking to it, and found himself at home again, revising the lyrics two decades after the Palace cave-in to narrate “life after Bush and Gorbachev” when “the wall is down but something is lost.” His band struts confidently behind him but there’s nothing dirty here, just “the news,” as Iggy describes his favorite tune, acknowledging how much this remarkably simple, eternal song has given him over the decades, a sturdy if beat-up suitcase he’s lugged around the world since he was a teenager. He can stuff so much inside of it, yet it never falls to pieces.

Halfway through, he nails what might be the perfect epitaph for this remarkable performer, this punk rock and roll lifer:

I think about the meaning of my life again

And I have to sing, “Louie Louie” again

Joe Bonomo writes about music for The Normal School. His most recent books are No Place I Would Rather Be: Roger Angell and a Life in Baseball Writing and Field Recordings from the Inside (music essays). Visit him at No Such Thing As Was, @BonomoJoe, and __bonomo__.