(4) joan jett, “crimson and clover”

outlasted

(6) patti smith, “gloria”

177-162

and will play in the final four

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Pacific time on 3/25/22.

david turkel on Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover”

“Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” —DuBeat-e-o, 1984

I’ve named the play “Crimson and Clover” because I don’t know what it’s about. I want people to make up their own meaning, the way they do when they hear that song. I want them all to think about something different that’s true for each of them.

It’s 1998 and I bartend in a place called Hell and Joan Jett’s version is on our jukebox. Or “little Joanie Jett,” as we call her—an homage to Alan Sacks’ trash film, DuBeat-e-o.

When I ask customers what they think the song means, they tell me a dozen different things, as if the title itself were a sort of Rorschach. One says the song is about a girl losing her virginity. Another says that it’s clearly about shooting heroin, the blood mixing with the “honey” in a syringe. Still another informs me that Tommy James—the writer of the song—was a born-again Christian and that the crimson represents Christ’s blood and the three-leafed clover, the Holy Trinity.

The lead actor in my play, Tom, was of draft age in December 1968 when the Tommy James and the Shondells’ version raced up the charts. He tells me the song has always been about Vietnam for him: “blood and land, over and over again.”

My play is about none of these things. Though it’s written in three acts, which could represent the Trinity, I suppose. And it has some sex and violence in it. Also heroin. And camel spiders. And St. Francis and surfing and the C.I.A. Mostly it’s about a billionaire named Arson (played by Tom) who wants to become the first man in history to cross the United States, coast to coast, entirely underground.

It’s my first play and I’ve been in therapy since I started it. I ask my therapist—a Jungian—if he wants to know anything about what I’ve written. He doesn’t. “Isn’t it like a dream?” I suggest. “Couldn’t that be useful?” But he doesn’t seem to think so.

Tommy James claims to have simply woken up with the words “crimson and clover”—a combination of his favorite color and favorite flower—stuck in his head. But that story was disputed by Shondell drummer Peter Lucia Jr., who co-wrote the song. For Lucia, the title sprang from the name of a prominent high school football rivalry in Morristown, New Jersey (where he grew up) between the red-uniformed Colonials and the green-Hopatcong Chiefs.

And so, oddly, even at the ground-zero of the song’s creation, there’s dispute over what the words signify. Almost as if they were birthed twining a spell of some sort—weaving mystery and confusion into the air.

On the Songfacts message board devoted to “Crimson and Clover,” contributor after contributor offers what each insists is its sole, incontrovertible meaning. Kayla from Dallas writes, “The song is actually about a beautiful girl with red hair and green eyes, get it?” Rex from the ‘Heart of America’ begins his post, “It really surprises me that so few people have this right” before launching into the most painfully halting description of coitus, like a squeamish father tasked with the birds-and-bees speech.

However the title came about, the story of the song itself is well-established, if no less magical. As Shondell keyboardist Kenny Laguna tells it, the band had just lost their chief songwriter and the guys were pushing Tommy James to find somebody new, convinced he didn’t have the chops to write a radio hit himself. Five hours later, James and Lucia walked out of the studio with the recording of “Crimson and Clover”—James having played every instrument except drums on the track.

He then took the rough mix to WLS in Chicago, where he spun it for the head of programming as well as a top DJ to get their impressions. At some point during the visit someone at the station pirated a copy, and by the time Tommy James had returned to his car the single was on the airwaves in its raw, unmastered form, being hailed by the DJ as a “world exclusive.” Before Morris Levy, the infamous mobster who ran the Shondells’ label, could intervene, “Crimson and Clover” was already a hit and on its way to its ultimate destination at number one on the charts. Many who heard it that holiday season in 1968, thought James was singing “Christmas is over” on repeat.

At a Christmas party in 1998, an inebriated dancefloor collision results in my girlfriend tearing her ACL. We’re too fucked up at the time to know what’s happened. But when I wake up the next morning, she’s there beside me, crying in her sleep from the pain.

She’s been cast in my play as Looloo, a twenty-five-year-old recovering heroin addict whom Arson meets touring a new hospital wing. Looloo is a patient there because she skied off a mountain in an apparent suicide attempt. So, it makes sense that her leg might be in a brace, we reason. Sometimes things like this just have a way of working out.

“Do the math,” Lon from Providence insists. “It is a poetic masterpiece...about a plaid skirt...the girl he had a crush on in school wore...hence the colors maroon (crimson) and green (clover), and then the pattern over and over..........”

My girlfriend and I are among the half dozen or so co-owners of Hell, where, until the accident, she was also a bartender. She’s the real reason Jett’s 1997 retrospective Fit to be Tied is on the box, and why we frequently holler out, in our best Ray Sharkey impressions, “Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” whenever it plays.

Sharkey portrays the title role in DuBeat-e-o: a movie director who’s on the hook to the mob for a new picture starring Joan Jett. In real life, director Alan Sacks (best known as a creator of Welcome Back, Kotter) had been hired to salvage botched footage from an attempted screwball movie based on the Runaways—the all-female, proto-punk band Jett founded with drummer Sandy West in 1975, just weeks shy of her seventeenth birthday. Sacks had fallen in with the L.A. Hardcore scene and his solution to the problem of trying to use bad footage to make a good movie, was to make an even worse movie about a megalomaniacal director’s fantasy of making a great one.

“See, I shot this film so that Joanie would come out looking hip enough to handle any situation. Understand?” DuBeat-e-o lectures Benny, the cough syrup-addicted film editor (played by Derf Scratch from Fear) whom he’s chained to an editing station at gunpoint. “I mean, that’s why I put her in every slimey, scummy situation of Mankind that I can think of, okay? I mean, the essence of my film—my film!—is that true talent, no matter where it comes from, has gotta come out—because it’s got fucking ENERGY! You understand?!...That’s why I’m the director! I got the vision, you prick!”

IMDB lists Jett as “starring” in DuBeat-e-o, but this is a Bowfinger-like deception, since she only appears by way of the archival footage Sacks was hired to edit, and as a picture adorning a wall in DuBeat-e-o’s seedy apartment. More accurately, Jett is hostage to the movie, her bottled image coopted to serve its baser designs; her ever-tough performance chops fronting the Runaways cut to look as if she’s delivering these efforts to please the leering countenance of The Mentors’ El Duce (who plays his slimeball self in the film).

And yet, perversely, it all works. Moreover, it works just as DuBeat-e-o, at his most deranged, said it would: Jett’s hipness—her ENERGY—rises above it all, untouched and unsullied. And the movie, either in spite or because of its many flaws (it’s really impossible to say which), truly exalts her.

In the 2018 documentary Bad Reputation, Jett—its ever-inspiring subject—avoids any mention of Sacks’s film by name, but merely shrugs it off as “some weirdo porn movie.”

Before I started tending bar at Hell, I knew next to nothing about Joan Jett, outside of “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll”—a single that peaked when I was eleven years old and inking “O-Z-Z-Y” across my knuckles.

I didn’t know about the Runaways or Jett’s affiliation with the Sex Pistols. Didn’t know that she produced the first Germs album and music by Bikini Kill. Or that she and ex-Shondell Kenny Laguna—her longtime collaborator and Blackheart producer—were forced to shill her hit-laden solo debut out of the trunk of Laguna’s car after it was turned down by twenty-three labels. In short, I didn’t know that Joan Jett was punk before punk and indie before indie.

But by 1998, not only do I know these things, forty-year-old Jett has recently turned up in a black-and-white commercial for MTV, flipping off the camera and sporting the close-cropped platinum-dyed hair that will become as iconic to that era as her black shag was to the seventies. She’s been going at it hard for more than two decades at this point, only to emerge looking fitter, tougher, sexier, more otherworldly than ever before, and I am becoming obsessed.

“And there was Joan in the black leather jacket,” Laguna says of their first encounter at the Riot House on Sunset Boulevard. “The way I remember it, there was razorblades hanging from it. And...I just never seen anyone like this. I was like, ‘Whoa! What is this?!’ And...I think I loved her right away.”

Ahhh, well, I don’t hardly know her...

“A little quiz for the Peanut Gallery,” posts Alan from Providence on Songfacts. “Crimson is my color and clover is my taste and aroma. What am I?” he asks, before adding, with a tacit wink, “And there is a reason Joan Jett loves this song.”

But I think I could love her...

Laura from El Paso concurs: “I have to say that when Joan Jett sings this song, for me it is impossible not to feel it takes on a whole new meaning. She is singing about ‘her’ and how she wants crimson and clover over and over.............”

And when she comes walking over

I been waiting to show her...

Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” arrests us, not only for those parts of the song she’s altered, but also for what she’s kept in place: the pronouns of the singer’s object of desire. Though Jett has said this decision was about preserving the integrity of the rhyme scheme, the seismic impact of hearing one woman sing so intimately to another—unprecedented on popular radio in 1981—can’t, and shouldn’t, be overlooked. Not because the choice scandalized certain listeners (I mean, seriously, fuck them), but because for many others this was a revelatory and liberating event.

As Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna puts it, “The first time I heard Joan I was in the car with my dad and it came on. It was ‘Crimson and Clover,’ and I heard that voice, and I was just like, ‘Who is this person?’ And then, when she would get to the pronouns and say, ‘she,’ I got really interested.”

At the same time, I think it’s important to take Jett at her word as a no-nonsense rock- and-roller simply working in the service of a great song. Certainly it’s true that, where rhyme was no impediment, she proved more than willing to make heteronormative adjustments. Case in point: her most famous cover off the same album, the Arrows’ 1976 tune, “I Love Rock and Roll”: “Saw her standing there by the record machine” became “saw him standing there.”

But what’s true in both cases is that Jett’s persona animates and subverts each narrative equally. Speaking for the eleven-year-old that I was when I first heard “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll,” it was a novel and noteworthy experience to be confronted by a sexually aggressive woman describing her recent conquest of a teenage boy in such tough, conversational terms. Like Hanna, or Kenny Laguna, I distinctly remember thinking, Who is this person?

Jett describes her own approach to inhabiting songs this way: “Part of it is having fun, and part of it goes back to...being able to do everything. When you’re singing songs about love and sex, you want everyone to think you’re singing to them. Whether you’re a boy, a girl, a woman, a man—whatever you’re into, I can be that.”

My, my such a sweet thing

Wanna do everything

What a beautiful feeling...

“The greatest voice you’ve ever seen”—that superlative from DuBeat-e-o—has never been showcased to greater effect than 1982’s “live” performance video of “Crimson and Clover.” At minute 1:28, Jett seems to be singing in harmony with her own eyeballs. Yes, sing the eyes, you know exactly what I mean... I would argue that as much as keeping the word “her” matters to this cover, the potency of Jett’s rendition hinges on her phrasing of the word, “ev-er-y-thing.”

What’s brilliant about Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” is the way she both queers and straightens the song. Gone is the drippy vibrato and underwater warbling which threatens to make the original a relic of Psychedelia. In their place, Jett and Laguna have punched up the guitars and amplified the dynamic interplay between the breathy, epiphanic verses and the riotous bounce of its instrumental breaks. In live performance, at the dramatic crescendo—Yeah!—Ba da! Da da! Da da!—Jett never fails to let go of her guitar and raise her arms fist high toward the audience. “Crimson and Clover” is an anthemic rocker, as she embodies it—a song about connection, celebration, ecstasy.

But what truly distinguishes Jett’s version from the Tommy James and the Shondells’ original, is that Jett actually knows what she’s singing about; Tommy James didn’t have a clue.

“People ask me what it means?” James told a Youtuber who calls himself the “Professor of Rock” in a 2019 interview. “Two of my favorite words that sounded very profound when you put them together. And just a three-chord progression, backwards.” For Jett, on the other hand, the meaning is clear. In Bad Reputation, she envisions the song from the perspective of the woman she’s singing to: “‘Oh my God, she’s gonna take me home and fuck the shit out of me!’ That’s scary!”

I don’t make this comparison to disparage Tommy James; cluelessness is possibly the single greatest feature of his music. He recorded “Hanky Panky”—his first number one hit and one of my all-time favorite rock-and-roll tunes—having only heard a garage band’s cover of the original and remembering almost none of its lyrics. His chart-topper “Mony Mony,” from March of ’68, cribbed its title off the acronym emblazoned atop the Mutual Of New York building, which loomed outside the window of James’ Manhattan apartment. In both cases, his ability to imbue nonsense words with infectious energy and devilish intentions earns him Kenny Laguna’s praise as “the Led Zeppelin of Bubblegum.”

With “Crimson and Clover,” however, James needed a song that would do the opposite— launch him out of Bubblegum’s playground on the AM dial and into the burgeoning FM market.

And while he loves to tell the story of how the title arrived in his sleep and how the song was a deus ex machina for his band (“I think my career would have ended right there with ‘Mony Mony’ if there wasn’t ‘Crimson and Clover,’” he told It’s Psychedelic, Baby in a 2013 interview), the real truth is that Tommy James had spent nearly two years clocking an impending shift in the musical landscape. At an earlier point in the same interview, he describes the moment in February 1967 when he heard “Strawberry Fields Forever” crossover to an AM Top 40 station: “That really left an impression on me.” A new audience was emerging for whom Pop’s infectious energy was not enough. They were hungry for something beneath the surface.

Or, at least, the suggestion of it.

Not to be outdone by the Songfacts sleuths, I have my own admittedly less romantic view of the real meaning behind “Crimson and Clover.” Whether consciously or not, the title is a “Strawberry Fields” analog. Red and green, verdant and evocative—Crimson and clover, over and over is Tommy James’s Strawberry fields, forever.

This suspicion only solidifies with a listen to the whole Crimson and Clover album, which wears the influence of that particular Beatles’ song pretty thin over its ten tracks. "Hello banana, I am a tangerine,” Tommy James sings at one point, sounding like a narc trying to bluff his way onto the Psychedelic school bus.

But look again at the same three songs: “Hanky Panky,” “Mony Mony” and “Crimson and Clover.” All three open on an image of a woman in motion. All three turn on a chorus of indefinite but suggestive meaning. What truly separates them, and what also separates Bubblegum from Psychedelia (“Sugar, Sugar” from “Mellow Yellow”) is that the former uses innuendo to hint at a song’s true meaning, whereas the latter employs it to the opposite effect— suggesting that the song’s meaning is deeply buried and perhaps not even fully available to everyone.

All of which is to say that, while Tommy James certainly knows how to inject a song with implied meaning when he wants to, with “Crimson and Clover,” he is deliberately trying not to say anything. It’s a masterpiece of indirection. Like a shell game with no pea.

Stage lights rise on a young man hanging upside down, his head in a bucket. This is the character of Jeffery, the surfer in my play. He’s been imprisoned in an unnamed country by fascist goons who have mistaken him for a writer. He hangs like this for a few beats, and then his interrogator enters and grabs him up by the hair. That’s when the soundboard operator cues the song: Ahhh...well, I don’t hardly know her...

Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover” kicks off act two of my play. This is the real reason why I’ve chosen the title—I want the song to feel like it’s stitched into the very fabric of the text, so that no one will mistake it for a directorial or sound designer’s decision. Like DuBeat-e-o, Alan Sacks, Kenny Laguna, Kathleen Hanna, I want Joan Jett’s bottled light to illuminate my dim interiors; I want to claim some of that impossible energy of hers for myself.

But my director has other ideas about the power source we need to tap into for our production. A week before we open, he introduces us to Robert, his guru—a professor from his grad school days. Robert speaks at length in a haughty British accent on the subject of “vibrating at a different frequency”—a discipline which he believes, once mastered, renders an actor utterly captivating to audiences.

We’re gathered in a circle where the only language we’re allowed is the single syllable, “bah!” and we’re instructed on ways to “direct our sound.” First, off one wall. Then two. Then off two walls and through the window out into the street, like a bullet ricocheting. Bah! BAH! “Put your bah into your chests,” Robert tells us. Bah! “Now into your stomachs!” Bah!

I’m afraid to even look at my girlfriend, there in her leg brace across the circle from me. This is everything I promised her theatre wasn’t. The total opposite of Punk rock.

“Now, put your bah into your left foot,” Robert, the guru, prompts me, dropping to his knees so that he can rest his ear just below my ankle.

“Bah!” I shout.

He looks up and says in earnest, “Don’t yell. It’s not about volume. It’s about putting your voice into your foot.”

The next day, he takes the cast to a mall, where, at full voice in front of the Cinnabon, he describes the milling shoppers as “dead people.” Our job as high priests of the theatre, he informs us, is to remind them all what it means to be alive.

When Tom tells the guru that he finds the mall patrons “electric,” he is banished from the inner sanctum. Meanwhile, my girlfriend has hobbled off with one of the other actors to get stoned in the parking lot.

Eventually, I too shuffle away in despair and embarrassment. The guru’s visit has cost us two thousand dollars and we can no longer afford the boat we need for the climactic third act scenes on the underground river. It’s just as well. I’ve lost all faith in my play by this point. All my big ideas have turned into mush. The monologues I was so proud of, despite all my actors’ best efforts, ring false and contrived.

There’s only one scene I care about anymore. Over the run of the show, it will be the only scene I consistently emerge from the wings to watch. I wrote it in five minutes and thought nothing of it at the time. It’s just a breakfast scene with the whole cast present. Everyone gathers in the kitchen, trying to start their day and pass the butter around the table. Arson and Bell, the scientist, discuss plans to launch his underground journey from the secret lab she runs beneath Mount Weather. Ed, the CIA operative, tells a crass joke to Looloo and Benedict—a psychic who’s recently been helping Arson communicate with the dead.

Jeffery is the last to enter. He’s been in bed for days, horribly sick from his ordeal. He’s shaky on his feet and not really certain where he is.

There’s something about the rhythm of this sequence I got right. The butter, the stray fragments of dialogue and competing conversations. The entrance itself, which isn’t clocked by everyone at the same time, so that it’s like a musical breakdown with all the instruments cutting out one by one. The particular quality of the silence that follows, as Jeffery stands there swaying, and Looloo slowly rises to meet him. There’s something about the way the actors have to extend themselves to fill the gaps in this scene; that’s where the life is, I’m starting to understand, in those gaps.

This is my first real piece of theatre. No one thinks twice about it but at least I’ve figured that much out. In performance, you don’t hardly know what you’ve written until someone else tries to make your words their own.

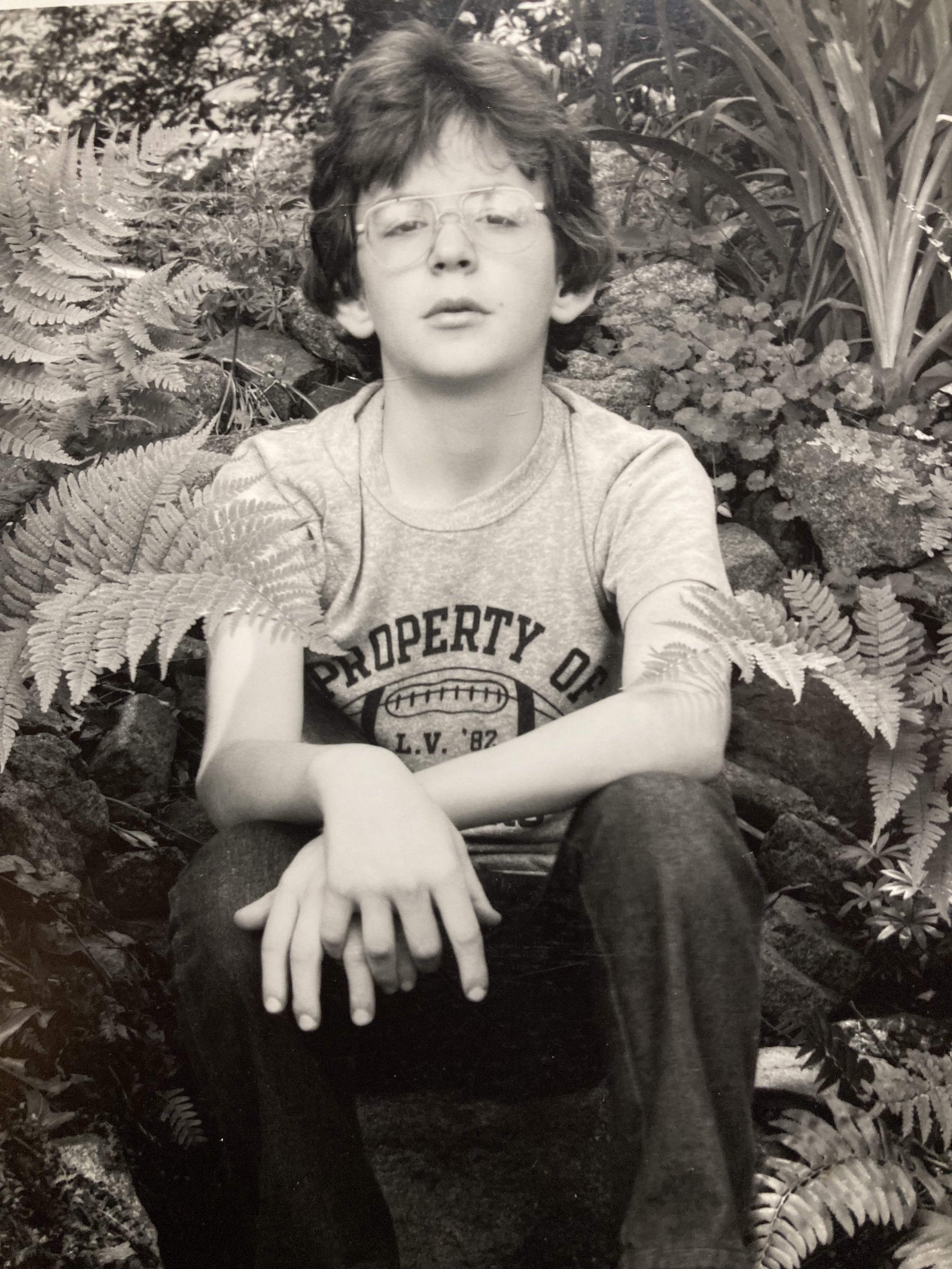

The author in 1982, the year Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” peaked at #7 on the Billboard Hot 100. Captured here in the wilds of New Jersey, without a clue in his mind that he is headed straight to Hell. And from there, eventually, Oregon. He will pick up bartending and playwriting along the way and would be pleased to know that he’ll one day land a gig writing about vampires for television.

ALPHABET OF DESIRE: ASHLEY NAFTULE ON PATTI SMITH’S “GLORIA”

G.

A believer is a horse in search of a rider. In vodou a worshiper who is possessed by a Loa spirit is sometimes called a mount. To be possessed is to be ridden, the human acting as a vehicle for the divine. When the avant-garde director Maya Deren documented vodou rituals and dances in Haiti, she called her 1954 film Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Deren had gone to Haiti to make a recording of ritual dances as an observer, but was so moved by the vodoun tradition that she became an initiate. She left the U.S. as a woman and returned as a horse.

The relationship between a spirit and its rider is the inverse of how humans deal with horses. Normally, we keep our mounts calm and form a rapport with them. We earn their trust so they’ll be willing to carry our weight. It’s different with spirits: you have to make them feel at ease so they’ll take you for a ride. You ply them with offerings of their favorite liquors and treats, maybe bribe them with a hand-rolled cigar or shiny bauble. You decorate your space with colors they like and wear the kinds of clothes they prefer, taking on their mannerisms for your own, hollowing out a space in your skull for them to make themselves at home. You say their name and sing their songs until you’re hoarse, following Aleister Crowley’s credo of “Invoke often! Inflame thyself with prayer!” You live and breathe as them until one day the spirit moves you and you are them. For a time. Until one of you throws the other off.

L.

Before “Gloria,” before Horses, before Mapplethorpe, before fame, before critical acclaim, before fucking Blue Oyster Cultists and playwrights and guitarists named after French Symbolist poets, before tours in Europe, before “Because the Night,” before THAT song that shall remain unnamed, before playing chicken with God, before Fred “Sonic” Smith, before retirement, before motherhood, before Law & Order: SVU guest appearances, before Just Kids, Patti Smith was a poet. She came to New York with dreams of making it as a decadent, renowned artist. Her heroes ran the spectrum of brows from high to low: Rimbaud, Bob Dylan, William Burroughs, Maria Callas, Brian Jones. The Beats, garage rock, and William Blake all vied for Patti’s affections but she wouldn’t commit to a single muse.

There were others who came to NYC with similar outlaw literary dreams: Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell. The three of them quickly realized that the glamourous spirit that once rode the Beats had moved on to popular music. People still fucked and feted writers but not nearly as much as they do rock stars, and besides— the musicians get better drugs and paydays. Had James Murphy written “Losing My Edge” in the early 1970’s he’d no doubt be warbling “I hear that you and your friends have sold your typewriters and bought guitars.” The spirit of rebellion didn’t want ink anymore; it hungered for electricity.

For Patti, the gateway to music was through poetry. It was through her St. Marks Poetry Project readings that she became initiated into the downtown art scene, where she first started working with her musical partner Lenny Kaye, and where she first blew that legendary raspberry at the Almighty: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine.”

“Oath,” the poem from which the opening line of Patti Smith’s “Gloria” is taken from, was originally a St. Marks solo piece. As recounted in Ray Padgett’s Cover Me: The Stories Behind the Greatest Cover Songs of All Time, Patti’s performances of “Oath” took on many different forms before it got merged into “Gloria.” The daughter of a Catholic mother and a father who “used to blasphemy and swear against God,” “Oath” is a hard dismount of her past, kicking off Jesus with a dismissive “I am giving you the good-bye/Firing you tonight.” With Lenny Kaye accompanying her on guitar at her readings, Patti heard her future career taking shape one power chord at a time.

O.

“Gloria” is not a cover in the conventional sense. It is a bricolage, a hybrid of the original Them song and Patti’s poetry. “Gloria” is not a cover, it is a hijacking. It changes the original so profoundly that it usurps it, renders it anemic in comparison. Through some kind of artistic time paradox the very existence of Patti Smith’s “Gloria’ has turned the original song into a cover of its own cover. The Them song feels naked without the (many) alterations Smith added to Van Morrison’s song: the “humping on the parking meter,” the stadium full of screaming fans, the tower bell chiming tick-tock tick-tock, “oh my god it’s midnight,” the piano notes that are perfectly timed to mimic knocking as she sings “she’s knocking on my door.” The one thing Van Morrison’s original version has going for it is Morrison’s feral vocals, all full of lusty swagger—the sound of a man who’s so horny it causes him searing pain.

Patti has done these kinds of rewrite covers before: her debut single was a heavily Pattified take on “Hey Joe,” and she would also throw in some choice ad libs when doing live performances of The Who’s “My Generation.” On “Land,” the song on Horses whose ecstatic visions of waves rolling in like Arabian stallions gives her first album its name, Patti breaks up her soliloquies about switchblades and sperm coffins to do a snippet of Wilson Pickett’s “Land of 1000 Dances.” Like so many great folk art traditions, Patti wasn’t afraid to file the serial numbers off of older work and repurpose it for her own ends.

Patti wasn’t the only rock singer/poet who took liberties with “Gloria.” Jim Morrison would do his own wildman poet take on the Them classic during Doors concerts, asking the object of his affections how old she was and what school she went to. Eventually the clumsy seduction between Jim and Gloria builds to the point that she sneaks him into her room while her parents are out and Morrison, in full blustering sex god mode, intones “Now why don’t you wrap your lips around my cock, baby” (the rest of the Doors chiming in with hoots and “suck it” ike the dorkiest wingmen imaginable transforms the line from sleazy to hysterical). Morrison narrates the positioning of Gloria’s lithe limbs around his body like he’s doing play-by-play commentary for a game of Twister. None of his additions to the “Gloria” canon seem essential or even necessary—all the luridness he makes explicit in his version is plainly evident in Van Morrison’s voracious, leering vocals.

Patti’s contributions are far more unexpected and poetic. Beginning the song with a soft piano intro, she sings her famous brush-off to the Lord before the rest of the band joins in. Patti doesn’t change the gender of the narrator or Gloria, singing the song as a woman in a man’s body—which gives the song its off-kilter energy, like an 80’s body-swap film where a woman turns into Van Morrison and immediately goes into horny cartoon wolf mode. The song sways and lurches in its tempo as it struggles to find a shape that will contain it, much in the way that Patti as a singer seems to be teasing out the possibilities of being a male character—taking both the song itself and masculinity out for a bumpy joyride.

“I can’t write about a man, because I’m under his thumb, but a woman I can be male with. I can use her as my muse,” Smith said in Please Kill Me. She would later tell The Observer that she “enjoyed doing transgender songs. That’s something I learnt from Joan Baez, who often sang songs that had a male point of view. No, my work does not reflect my sexual preferences, it reflects the fact that I feel total freedom as an artist.”

The Gloria in the two Morrison versions of the song is a sexual conquest, an object of desire to own and tell the world about (and in Jim Morrison’s case, someone to patronize: “why did you show me your thing, babe”). Patti’s Gloria is more complicated. The singer almost seems afraid of her, intimidated by how wild Gloria is—the sweet young thing enters the song’s orbit humping on parking meters, as uninhibited as Darling Nikki under a magazine. Listen to the strain on Patti’s voice when she sings about “her pretty red dress,” the tremulous gasp of someone who wants something so badly and is afraid they’re going to get it. Smith’s Gloria is a figure of lust and awe, a challenge, a free spirit looking for a body to call home.

When we finally get to the chorus, the guitars and drums gallop as they rush headlong into Smith’s invocation of her lover, inflaming herself with the letters of her name. You can hear the roles shifting as she gnaws and spits out each hickie-mangled letter: she goes from prey to hunter, from deer-in-the-headlights to speeding Cadillac, from horse to rider. Smith’s “G-L-O-R-I-A” is her victory lap, celebrating her freedom from God, from the rules and regulations of Man, from gender itself.

For Van Morrison and Jim Morrison, the song is about a man finding himself by fucking a woman. For Patti Smith, “Gloria” is about a woman finding herself by being a man fucking a woman,

R.

God, sex, and the liberatory power of rock & roll are the animating spirits behind “Gloria.” You can hear Patti wrestling with this trinity in “Piss Factory,” the B-side to her debut single. The Patti in "Piss Factory" is a "speedo motorcycle,” a fast worker whose productivity rate is too high for the pipe factory that’s paying her “screwed up the ass” wages. Browbeaten by her floor boss and by a “real Catholic” coworker who threatens to beat her in the bathroom if she keeps throwing off their quota, Patti daydreams about bringing a radio to work so she can listen to James Brown scream and sigh instead of the mechanized chorus grinding around her. She steals glances at the nuns living in a convent near the factory. “They look pretty damn free down there,” she croons. “Not having to worry about the dogma of labor.” It’s like Dylan says: You gotta serve somebody. At least you don’t get your hands burnt up in God’s factory.

Patti sees a final escape hatch in the form of gender. “I would rather smell the way boys smell,” she snarls as the music thrashes behind her like factory equipment struggling to meet a rush order. She rhapsodizes about the “forbidden acrid smell” of “roses and ammonia” that rise from their drooping dicks, lamenting that all she can smell is the “pink clammy lady” odor of the women laboring around her—hardened, dead-end women with “no teeth or gum or cranium.” She wants the freedom the bad boys sitting in the back of class have—not by enjoying it vicariously through fucking them or hanging on their arms but by taking their cockiness, their who-gives-a-shit swagger, for herself.

“Gloria” is this Promethean moment for Patti, where she steals the fire from the male artistic gods she venerates and runs with it. It’s the moment she was building up to since she arrived in New York. Reading accounts of her time in the NYC scene, it’s easy to see why people accused her of being a careerist: laser-focused on emulating her heroes, hob-nobbing with Warhol at Max’s Kansas City, getting in good with all the local literary luminaries, always “on” as though she were rehearsing for the role of Patti Smith: Punk Poetess before it existed. But from a ritualist’s eye, Patti’s early years take on a different light.

Patti did what she had to do to summon the same spirits that rode Rimbaud and Brian Jones. She left her family, cut ties with her past, and started anew. She inflamed herself with the names of her heroes and invoked poetry and rock & roll as often as she could, until she could hollow herself out enough to coax the same dark angel that spread its wings over the Beats and Lautreamont and Gene Vincent to move into her. And thus the trap was sprung: she grabbed that spirit and rode it for dear life. “Gloria” and the rest of Horses is Patti trying to answer the question “am I the horse or the rider?”

The sound on Horses is unstable and manic, the band trying to keep pace with her hipster glossolalia. Compare it to the music of her fellow poet-turned-rocker Tom Verlaine, whose own masterpiece/debut Marquee Moon takes a more Apollonian approach to her Dionysian rock & verse. Marquee Moon is a twilight rollercoaster, Verlaine and Richard Lloyd’s twin guitars ascending in pristine loops and curves, sliding down through a landscape of neon signs and piss-stained floors and barroom napkin poetry. Television are Apollonian detectives—stiff, beautiful, regulated—forever running in circles after a mystery they’ll never solve. Television’s music is as clean and dry as an unlit match. Every note on Horses is a blackened match-head.

I.

If we could resend the Voyager probe with a new golden record, it only needs two brief pieces of music to represent the whole of rock music: a vocal loop of Iggy Pop screaming “LOOOORD” at the beginning of “TV Eye” and a sample of Patti gnawing on the “I” in “Gloria” like it’s the bar on a jail cell door she’s trying to chew her way out of. Pure lust and rage, defiance and triumph, fuck-you and fuck-me all co-mingled in the briefest of exhortations from two of our greatest singers. The aliens don’t need anything else.

A.

“Jesus died for somebody’s sins, why not mine?” Patti Smith retired in 1979, playing a final concert in Florence. They normally saved “Gloria” as their closing number, but on this last concert before Smith walked away to devote herself to starting a family she made it the opening number. She also changed the opening lyric, offering up a reconciliation of sorts with the Christ she fired back at St. Mark’s.

Smith’s relationship with her fired God had changed over the intervening years. She used to do a bit during live performances of “Ain’t It Strange” where she would challenge God by taunting “C’mon, God, make a move” and start spinning onstage. During a show in Tampa in 1977, her game of chicken with God finally sent her sailing over a cliff—Smith tripped over a speaker while dancing and fell 15 feet into a cement orchestra pit. A freak accident or divine intervention, it had the effect of sidelining Patti and her band right as the punk scene they helped foment in New York went global.

Smith’s late 70’s embrace of faith and family seems baffling at first. So much of her artistic life was a refutation of both traditional religion and domesticity. Her fear of being trapped in another piss factory with real Catholic shithead coworkers fueled her drive. For someone who seemed to devote every waking hour to becoming a rock star, who devoted an entire verse in “Gloria” to the fantasy of rocking a stadium where all the girls are there to scream her name, giving that all up is confounding.

But try to imagine being laid up for a year, recuperating from a fall that nearly crippled you. You think of all your heroes, and how so many of them died young: Jones, Hendrix, Joplin, Rimbaud. The spirit rode them hard and stabled them under six feet of dirt. That’s the trade-off if you stay a horse in the art world for too long: you could end up dying face down in a pool or waste away delirious & one-legged in a hospital in Marseilles.

Faced with the prospect of going from “Piss Factory” to the glue factory, surrounded by scene peers like the Dead Boys who were busy living up to their names, a second act staged around faith and family must have looked like a pretty safe bet. If having a brief Godly face turn was good enough for Bob Dylan, who could blame Patti for wanting to steal one more move from his playbook? And so Patti completed her personal concert tour of Damascus, going from Saul of Tarsus to Saint Paul in just four albums.

P-A-T-T-I

The spirits move in and out of the world, taking their laps on borrowed legs when the right person comes along. Some of their horses die, some are forgotten, and a few are as eternal as Muybridge’s race horse—their grace and power preserved in snapshots by their works on this Earth. Horses, Radio Ethiopia, Easter, and Wave endure because they sound like nothing else. They are messy and beautiful and sometimes they over-reach and fall into orchestra pits. But they all come a distant second before “Gloria,” one of the greatest acts of homage and vandalism ever recorded.

Dave Barry once joked that "if you drop a guitar down a flight of stairs, it'll play "Gloria" on its way to the bottom." At the time he made that joke he was referring to the Them song. Drop a guitar down a flight of stairs today and you’ll hear a different voice echoing out of that hollow body. And her name is, and her name is, and her name is—

Ashley Naftule is a resident playwright and the Associate Artistic Director at Space55 theatre in downtown Phoenix. They’ve written and produced five full-length plays: Ear, The First Annual Bookburners Convention, The Canterbury Tarot, Radio Free Europa, and The Hidden Sea. Their next play, Peppermint Beehive, is set to premiere this summer. As a freelance journalist, their work has been published in The AV Club, Pitchfork, Daily Bandcamp, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Vice, Fanbyte, The Outline, Longreads, Phoenix New Times, Echo Magazine, The Arizona Republic, and The Cleveland Review of Books. Their short fiction has been published in Coffin Bell Journal, AEther/Ichor, The Molotov Cocktail, Cabinet of Heed, Grasslimb, Dark City Mystery Magazine, Hypnopomp, Write Ahead/The Future Looms, and Planet Scumm. Their micropoetry chapbooks Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth and Epoch & Olivetti Sing All The Hits are available (respectively) via Rinky Dinky Press and Ghost City Press. Despite the uncanny resemblance, Ashley bears no relation to country singer Vince Gill nor is in any way an evil Vince Gill doppelganger that escaped from The Black Lodge.