round 2

(10) The Sundays, “Wild Horses”

galloped past

(2) Janis Joplin, “Me and Bobby McGee”

223-207

and will play on in the sweet 16

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/15/22.

Karen Lentz on Janis Joplin’s “Me and Bobby McGee”

“Me and Bobby McGee” is a love song and a road song that uses neither of these words. Kris Kristofferson wrote it when he was a helicopter pilot, transporting rig workers back and forth in the Gulf, during an actual rainstorm on the way to Baton Rouge. You can bet that Janis Joplin was familiar with that kind of rain, hailing from the oil town of Port Arthur, Texas, and also with hitchhiking, not just around New Orleans but for the long haul, from Texas to California.

“I want to do that,” Janis said when she first heard “Me and Bobby McGee,” from Dylan associate Bob Neuwirth, hanging out with friends at the Chelsea in 1969. She picked up the guitar, wrote down the words, and “sang the shit out of it right on the spot,” according to Neuwirth, who added, snarkily or not, that “it wasn’t as if the chords were hard.”

Besides “Bobby,” Kristofferson has had many of his most well-known songs famously covered by others, e.g., “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” “For the Good Times.” One might expect some sort of artistic resentment about this, but Kristofferson called it exhilarating, and in the case of Janis Joplin singing “Me and Bobby McGee,” described it as the greatest feeling in the world, to see her make it her own.

Kristofferson’s songwriting was a departure from country music of the time, which generally relied on the sort of rhyming couplets embodied in the classic songs of Patsy Cline, where you can often guess the next line. There is, in the first verse of “Me and Bobby McGee,” however, the internal rhyme of “flat in” and “Baton,” “waiting” and “faded,” and the long lines rhyme train and rained, Orleans and jeans. The opening verse puts you in the cab of the truck that offers three things: a ride, music, and shelter.

This is the scene that the rest of the song takes place against: the crowded warmth of the front seat, jamming with just one’s own body and a harmonica, the rainwater pouring down and the windshield wipers doing their job against it. The splashes on the roof, the whisssh of the rubber tires on the highway, the glistening of the pavement, the shades of gray clouds, the headlights boring through it… who wouldn’t want to relive those hours? They settle into the understatement of “good enough for me.”

To rate an experience as good enough for you means to not need or even want any more. Whatever else might be on offer, it can stay out there. The thing about finding a place like that, when you listen to how Janis sang “Me and Bobby McGee,” is that it is always temporary.

“I sometimes think she may have been personally responsible for the explosion in the use of the word ‘fuck,’” an Austin friend said of Janis. When the city of Houston lifted its ban on rock performances in 1970, it made an exception for Janis Joplin, “for her attitude in general.” The story of her life generates a mixture of compassion and annoyance, awe and anxiety, crossing her out-of-bounds personality and substance abuse, her devastating live performances, her sexual appetites, her death at 27 of a heroin overdose.

I wanted for her some happy interludes, and was worried I wouldn’t find any. But I did—on a camping trip, which has to be about the furthest activity from her persona. Her friend and roadman Vince Mitchell remarked that he had never seen her so happy, describing her setting up the campsite and cooking in silver boots and popping up from her sleeping bag saying in sheer joy and discovery “You mean, this is camping!” The problem is, there were so few of these times in her life.

That hour in the cab of the diesel, with the music in the rain—that is, for the first-person singer, an exception. It’s not like that togetherness happens all the time, and she seems to know it is not to keep. The connections are transitory, and that sharpens their memory. You probably know the kind of hours I mean—where you would, if you could, freeze time. The wet dirt of a forest floor, the glow of a cherry flavored beer, the top of a hotel casino in an earthquake, the muscle curve of a plaid flannel shoulder with just a hint of woodsmoke and nightclub cologne, laughing like maniacs at something dumb. It’s a kind of focus, the connection: part of the headiness is not from what appears but from what disappears, not the drunkenness but the freedom, the shedding.

Neuwirth was right that “Me and Bobby McGee” is not hard to play. As an elementary guitar player, I was surprised how easily I could do it. I was all in for the Baton Rouge rainstorm, but I could feel the song picking up steam in the key change from G to A going into the second verse. The key change takes us to Kentucky, California. The narrator and Bobby cover ground from east to west, racking up shared episodes of misery, drudgery, heat, glory, and reprieve. Performing the divination of the road: what does this wood tell us, this tree, this motel, this truck stop. Where will we sleep tonight.

Some of us are never without this thought: I could be GONE. Pick a highway, any highway, Highway 9, Highway 67, Route 39, I will drop what I’m doing and take it, any and every time.

To know and love this song, it helps to have been a lot of places. I would have always been a highway woman, but I might not have gone so far afield except that in the early 2000s my life intersected with the Internet. Not what you could do on the Internet, but the Internet itself. I had not thought of it as a thing that needed to be taken care of to make sure it survived. It was the first job I had that was not too easy; rather, it was too hard, which I guess is what makes a career. I was dazzled by the fact that my work touched the entire world and it touched me back. I didn’t have a passport before that, but then I had to get the kind with extra pages, and that became a life.

This is the money line in the song, quoted all over and it still can catch you off guard when it comes around:

Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

It’s the line that, if you are listening in a car or singing karaoke, someone near you will do that intake of breath with a sound that, if it forms a word, is essentially—oh. And there are two kinds of people in the world: those who make the sound and those who don’t.

Kris Kristofferson was one of those all-around guys, in turn a football player, writer, Rhodes scholar, Blake poetry fan, musician. He left a plum job offer at West Point for the chance to write songs in Nashville - songs of experience, songs for grown-ups, songs for fringe dwellers. To walk away from a perfectly good life because of some wild longing requires that you do violence to your life as it exists, to the sleepy sad people who have done nothing wrong but do not hear the frequency beckoning you away. To free yourself from anything is, inherently, a loss.

At age 22, Janis returned from San Francisco to her parents’ house, weighing 88 pounds and sick and scared by her own addiction. She stayed there for a chunk of 1965, talking about becoming a secretary and avoiding singing, drinking, or any other possible gateways. She gave every indication of trying to locate her life in this—“trying” being the key word. You get the sense that part of her really wanted that—to put to rest the need for any more exposure, any acts of ambition. She could only see it, though, as a requirement to change herself. When she left town again for Austin, which would lead to her Big Brother gig, she told her therapist “I’m going to go be what I am.”

And to continue, to achieve, requires leaving more people and places behind. Janis agonized over leaving Big Brother to go solo for months, likening it to a divorce. It meant alienation from her community, her band, and even many of her fans. It could have been a huge mistake and she knew this. “But if I had any serious idea of myself as a musician,” she said, “I had to leave.”

The compensation for each of these losses may be success—like Kristofferson’s in Nashville, or Joplin’s European tour and the recording of I Got Dem Ol Kozmic Blues Again Mama. Or it may be the high of freedom itself—like breathing full into the open night after escaping a too-hot room. There are glories and caverns to freedom: the feeling of liftoff, of leaving shore, the semi engine rolling over in the morning, the dawn coffee, the road curving out of a town that you will never see again, the freeway entrance. A life like this possesses an undeniable attraction, for those who live it and those who watch. Motion itself keeps at bay so many epiphanies, that advance toward you once there is stillness.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing, Billy Parham has been a drifter in Mexico for a few years when he meets an old man who tells him that, although he is an orphan, “he must cease his wanderings and make for himself some place in the world because to wander in this way would become for him a passion and by this passion he would become estranged from men and so ultimately from himself.” I do not think Janis would have disagreed with this. But I do think she couldn’t figure out how to find the place in the world that was hers.

A pilot once told me that anyone who has done it two or three times can successfully navigate a plane into the air; it is the landing that throws wind and angles and geometrical illusions at you, and for that you want a professional. For that is the most dangerous.

Performers like Chrissie Hynde and Melissa Etheridge, talking about growing up watching Janis, mention reactions of fascination and fear. The hair. The emotion. The screaming. Critic Paul Nelson said that Janis Joplin does not so much sing a song as strangle it to death. It is true that she demands a certain kind of attention. Janis Joplin did not sing background music.

As a musician, she was essentially self-taught, her singing based on hours listening to radio and records, hours of imitation and experimentation. She never took lessons because she thought the teachers would want her to sing differently, which they almost certainly would have. One cannot wail in public the way that Janis Joplin wailed in public. So many people found her grandiose and egotistical and invested in things like magazine covers and who else got invited to perform before her, but simultaneously insecure, often labeling herself a street freak rather than a real musician. How sadly circular, to cultivate a whole personality as a free spirit who doesn’t care what anyone thinks, and then be constantly on the alert for what people think of it.

Her catalog of songs hits on certain notes again and again—loneliness, pain, now, then, and always, which was part of her own integrity. She never was interested in singing lyrics that didn’t reflect her experience. “My gig is just feeling things,” she said once. Her singing is to tell you everything about what it feels like to be her, and this may be the secret to why it is so affecting. Why listen to some secure, happy, well-adjusted person, to tell you about what you will never understand? Even voices that are stunning in the musical sense sound curiously flat after listening to Janis Joplin. Held back. Tame. Constrained.

It was almost always after a show, not before, when she reached for heroin. The time when one would expect to relax, exhale, relive the highlights—and she did do that, but still at the end of every night you have to go someplace, and for her that was often an empty motel room. She was, by all accounts, extraordinarily disciplined when it came to being ready for a show. It was afterwards that she flailed, no less from success than from failure.

When I used to travel for business, I’d be overtaken by a wave of homecoming joy flying back over Los Angeles and the lights of 3 million people swirled over the mountains, as the wheels janked out of their cages and the phones got turned back on. I’d move robotically through the lines for passports, luggage, bathrooms. And then, as I passed through the sliding doors, the same scene—a vehicle glides up, the trunk automatically unlatches, somebody slides their bag into the hatchback and gets in the passenger side, and they drive off. A vehicle glides up, pops the trunk, and a person gets out of the driver’s side and hugs the passenger, lifts their bag into the trunk, and they both scurry back to the car and drive off. All around me as I waited for the crosswalk light to change. It was impossible to believe, somehow, that I had come so far, from the other side of the globe, engineered some great professional success or endured a failed one, navigated three flights and six cultures and the physical travail of stale air and cramped space for 22 hours, and yet it mattered to zero people here, where I lived, that I had come back.

Liftoff feels like freedom, or can. But on returning to the ground, it does not feel like freedom; it feels like lugging a bunch of heavy stuff up the stairs because the elevator is broken. I should add maybe that plenty of people would have come to get me from the airport, had I asked. It was the automaticness of it that was lacking. The line of headlights coming into LAX formed an endless river: look back as far as it can go and none of them were coming for me, and it broke me every damn time.

Something like this is what I think it must have been like for Janis Joplin; there is story after story of her taking her audience through a spiritual experience and then being found later having a drink by herself. After the applause, the parties, after going out to dinner or to the bar, or to someone’s apartment, or to a lot of bars, at the end, everybody is supposed to go home. Imagine the anticlimax of being Janis Joplin, giving the kind of performances that Janis Joplin gave, and to have the night end up with the sound of flipping on the lightswitch in the silence. Music publisher Sam Gordon said, “Sure, Albert [Grossman, her manager] was there a phone call away and the band was there for tunes and the wine store was down the block and there were freaks in the lobby for her entertainment. But after that, it was just a situation with four walls, a chick laying in a fucking hotel room with nobody and nothing.” Imagine the extreme experiences of audience adoration and utter aloneness afterward in such proximity.

She loved and needed the adoration of crowds, but it was adoration that was spontaneous and generated rather than decided, committed, maintained. What happens near Salinas when the narrator goes one way and Bobby another—you can imagine this in many different lights. What feels true here is that she wants Bobby to find his home—you would want this for anyone you love—but there’s no expectation that she is going to find hers. The original was “looking for the home I hope she’ll find” … but in Janis’s impetuous “I hope he finds it,” that home is a fully formed place, delineated in wood and acceptance and feeling whole in one’s own life.

No matter how exhilarated or tired you are when you arrive, sometimes you put down wheels at a way station, staying with friends, where the wood is polished to a honey color and the soap smells like an apple-cucumber cocktail, and time rests in huge space, the hardest part of the day is backing the car out of the garage, and they go to bed early and the pillows are clean and the air soft as anything comes through the windows, and you marvel that they live like this all the time, and you leave with a lot of questions.

One of the more famous Joplin quotations is “I'd rather have 10 years of superhypermost than live to be 70 sitting in some goddamn chair watching television.” That’s the one they include in the motivational posters and calendars.

Her publicist and later biographer Myra Friedman recalls Janis saying once: “Ya wanna know something? Just give me an old man that comes home, like when he splits at nine I know he’s gonna be back at six for me and only me and I’ll take that shit with the two garages and the two TVs.”

And Friedman protests that she’s kidding, and Janis says “No I’m not, man. I’m not kidding at all.”

She said, and I believe meant, both things. You can find enough anecdotes to support either contention about what she “really” wanted, but the whole idea of her only being allowed to want one or the other is so frustrating. People need adventure. People need safety. You learn to detect the overtones of punishment at having your life reviewed—you wouldn’t be alone if you weren’t out globetrotting, trying to be someone in the world.

Janis wrote in a letter to her family in 1970 that ambition was not necessarily about scrabbling for position or money, but about what you needed to be loved and to be proud of yourself.

Bantering in a concert in the middle of “Cry Baby,” she talked disparagingly and quite directly about an ex running from home and love, how he was going to wake up in Casablanca one morning and wonder “What am I doing in Casablanca, man?” I know the moment she means—using the exact same words, what am I doing here, only instead of wonder and delight (wow, that’s the Persian Gulf), they come with weariness and disgust (what city is this, I have lost track, they all look the same). And anyone who keeps pushing themselves to the next act, who keeps reaching for more, greater adventure as the solution, knows the exact moment when that goes bankrupt.

This is what makes a story: a turning point, realizing what you want and going back to it. A journey is supposed to have an end, otherwise you are still out there on the road stopping at a series of temporary homes, trying to find one place that blends everywhere you have been and everything you want. It keeps you out there with your energy stretched out in increments trying to create a narrative, trying to tell yourself there is any pattern or logic or internal coherence to this life. Imagine if the Odyssey just ended with Odysseus coming home and there was no Penelope, no Telemachus—what kind of story would that be? The homecoming of Odysseus if he simply goes back to where he used to live, says hello to his servants and maybe visits some people.

Janis bought a house in Larkspur and dreamed about finishing the tour and living a rustic life walking with her dogs by the creek, waking up to a picture window of redwood trees. Same fantasies as we all have about quitting what’s hard and making life easy. Only when she did that, it was a disaster, with her hurtling back and forth to Sausalito to party all day every day, pulling into the crazed orbit everyone who came to visit, including Kris Kristofferson.

At many points in her biography, Friedman recalls reminding Joplin of the option to quit. She didn’t have to keep touring like this. She had the money, the house, she could control her own schedule, perform or record when she wanted. Janis’s response, out of all I read about her, is the line that haunts me the most: “I don’t have anything else.” Stay in the grind of a career, the road, the next destination, anything to keep it going, anything but the landing. “Me and Bobby McGee” is the song for when someone else—almost everyone else—has settled, has landed, and you cannot figure out how.

Wanting to trade multiple tomorrows for one yesterday suggests a person who believes their past is better than their future will be. Alas, no one comes along offering such trades, and the song is the ballad of knowing perfectly well that Bobby ain’t coming back.

There is no screaming from Janis in “Me and Bobby McGee.” This is a country song, a natural for her. You can hear the fun in her voice, rolling over the lalalalala’s in the coda, which have turned out to be my favorite part to play. She’s killing this song and she knows she’s killing it. It’s the Janis of the Monterey Pop Festival, after “Ball and Chain” as she has cried and crooned to the audience, so happy with the applause and doing a little skip as she crosses the threshold backstage.

The “Me and Bobby McGee” track was recorded on September 25, 1970, as she had just over a week left to live. It was released on her posthumous album Pearl, and became her biggest hit, staying at #1 for two weeks in March 1971. It has all her moods: humor, anger, fierceness, abandonment, longing. It was made for her, or she found her home inside it.

Because she died young, we never saw Janis Joplin reach the midlife juncture of someone who has been Out There on the edge for years, made a life out of movement and notoriety, asking the questions of what do I want? Have I accomplished enough? Have the things I’ve accomplished been the ones that matter most? Shall I now shrink back into the suburbs from which I came, and who am I then? Will I become bored, or worse, boring? To whom? What is it that I am afraid of?

I’ve been rambling around Hollywood this California winter, not because it’s an inspiring place but because it’s where Janis Joplin spent her last day, in the studio and then in Room 105 at what is now the Highland Gardens Hotel. Her Walk of Fame star has only been there since 2013, in front of Musicians Institute and surrounded by those of Hall & Oates, Adam Levine, and Journey. I keep thinking of what to go put there as a tribute, but I walk down Hollywood Boulevard aimlessly wondering about roses and pearls and feathers and Southern Comfort bottles because none of those seem right. I haven’t figured out what ambition means in the world of the 2020s, whether it exists or is only changing shape or form, or how it can help me save this overgrown beast city that I love so much.

The only thing I can think of is go home and put on her record. Turn it up, man. How long do you think we have.

Karen Lentz is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her words in Delos: A Journal of World Literature and Hippocampus. She has an MFA from American University and an MS in Journalism from Northwestern University. In 2013, she lived in Chapala, Mexico, as the first recipient of a 360 Xochi Quetzal writing fellowship. She is Vice President of Policy Research and Stakeholder Programs at The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Find her on Twitter @estreetlove.

WILD HORSES, CARRY ME AWAY: MORGAN RIEDL ON THE SUNDAYS’ WILD HORSES

to the horse I rode away, and to my mother who wouldn’t leave but let me

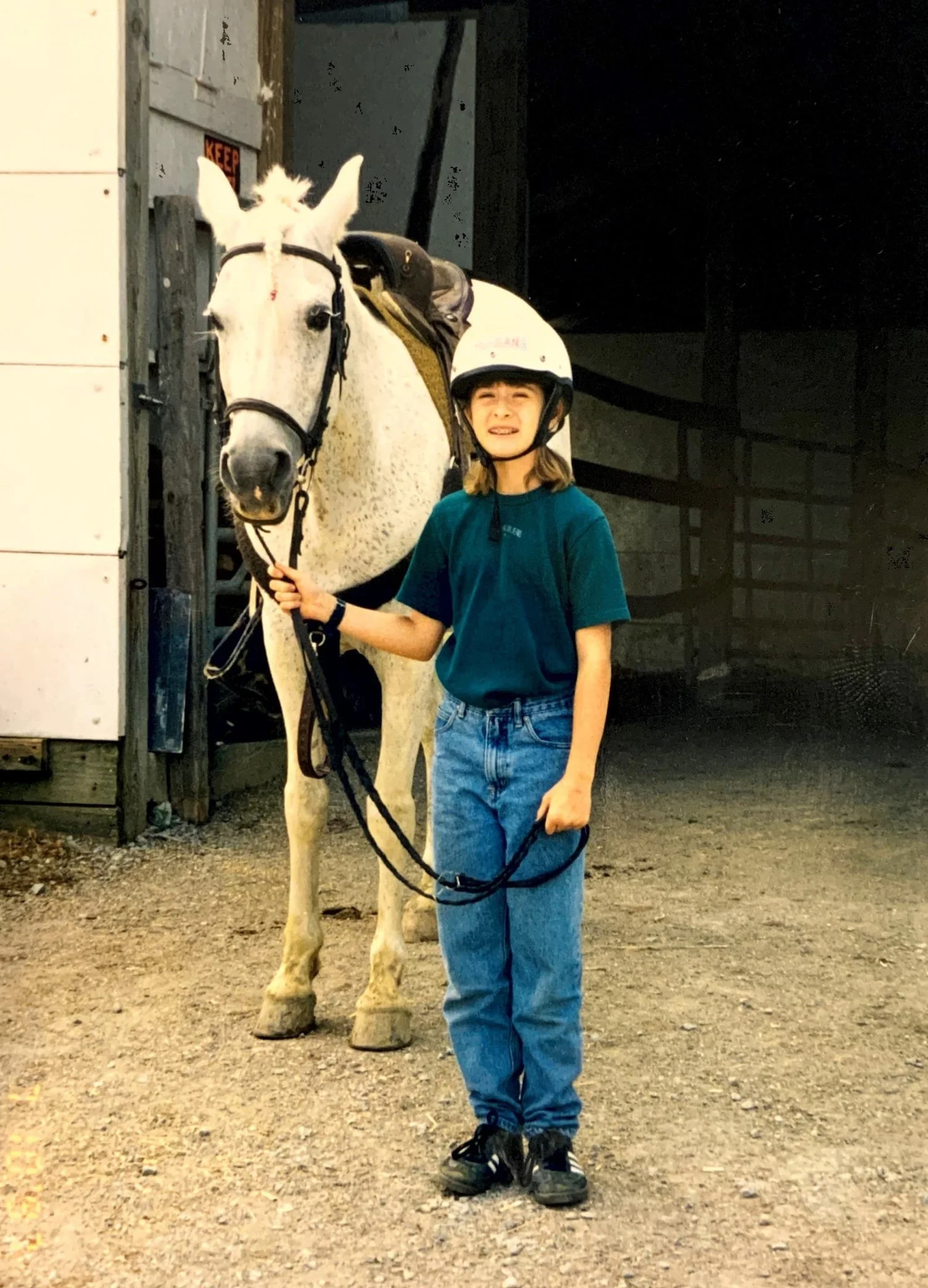

My fate rested in the hands of two high school students on summer break. The pony-tailed girl standing before me in an overlarge T-shirt sized me up, then turned to the demure boy beside her and said, “She’d look good with Bob, whaddya think?”

I hoped he would disagree because, even though I didn’t know who Bob was, the name sounded old and dull to my ten-year-old ears. But the boy nodded, and so decided my fate.

I’d wanted to be matched with a black horse like the one in The Black Stallion, and Bob was flea-bitten grey, or what my younger sisters called “white with spots.” In most ways, he wasn’t anything like Shetan, the wild black stallion whose name means “devil” in Arabic. But in the one most important way, he was. He carried me.

At the end of the week, rather than practicing how to maneuver though obstacles like cones and bridges in the indoor arena, the instructors led us to a trail around the lake where, one at a time, we cantered the perimeter. I’d already seen how sitting on Bob’s back made the pieces of the world fit more neatly together. But as he and I flew around the lake, I discovered it was possible to escape the puzzley world altogether.

Nearing the lone tree at the end of the loop where I was supposed to slow, I wondered what would happen if I—just didn’t. If instead I leaned forward, pressed onward and let Bob take me away. I saw us leave the ground and everything behind.

Four years later, I was still stuck on the ground—I’d even burrowed under it, holing up in my bedroom in the basement where I kept a huge dictionary to launch at the wolf spiders that trespassed. With Webster’s beside me, I watched Buffy the Vampire Slayer on my little DVD/VHS-combo TV, sucked into a subversive world where a small girl isn’t helpless but a hero. The chosen one. Even while saving the world, Buffy still dealt with the same mundane problems I did, from divorced parents to school dances. This was before vampires shimmered rather than combusted in the sun, but Buffy loved one anyway. Until he left. Maybe even after.

In the season 3 finale, Angel breaks up with Buffy because of everything he can’t give her, and although she realizes it’s for the best, she’s still devastated. Ends aren’t easy, even the ones you want. Still, in the episode’s last scene, Angel surprises her at the prom for a final dance as The Sundays’ cover of “Wild Horses” plays.

In Harriet Wheeler’s voice, I heard what the characters couldn’t say. I love you and goodbye. Delicate and elegiac, the vocals floated above the ground and made me remember what it felt like to leave it for a while. And beneath was a wistfulness I understood but only later discovered a word for: hiraeth—nostalgia for a home you can’t return to or one you never had. I replayed the scene again and again to listen to the song and feel the mournful aching of a loss I was trying to move past.

CHILDHOOD LIVING IS EASY TO DO

We’d been in our new house on Robinwood just a couple of weeks when my dad left a note on the counter and, with it, left us behind. At first, I didn’t know if I’d ever see him again, and for a while, I didn’t. Mom couldn’t tell me where he went or why. His leaving was a mystery I couldn’t solve, even after years of pretending to be the Great Mouse Detective. Back in our old house, I’d wear my plastic mouse nose and become the great Basil of Baker Street, and Dad would leave rhyming riddles around the house to lead me to where he was hiding. This time he didn’t leave any clues behind.

He did leave Mom a weekly allowance that didn’t go far with three kids, one still in diapers. We lived on cereal, PB&J, and mac & cheese until Mom went back to working nights at the hospital. But the job didn’t last long once Dad started getting flaky with weekend visitation. I’d sit on the steps where our walkway met the sidewalk, watching for his maroon Pontiac to turn the corner. In the beginning, I waited hopefully and was disappointed if pickup time came and went without him. When that happened, Mom scrambled to find last-minute childcare for the night. If she couldn’t, she called in sick. I learned you can’t be sick forever—the only thing you can be forever is gone. After a while, she gave up and went to work for her dad. It was less money and fewer hours, but she was home when we were—and when Dad wasn’t.

Weeks came and went. Mom tore pages off her monthly calendar, and I started to dread waiting for Dad on Fridays. I moved my sitting spot from the steps at the end of the walkway to the front porch steps. I watched not the road but the sky, wishing for the kind of weather that canceled the tennis lessons I hated taking. Eventually, I just stayed inside and watched the clock. I’d peek out the window around 6 p.m., hoping I wouldn’t see his car pulling up to the curb. Since he was often late, I never knew when to stop holding my breath. Fifteen minutes? Thirty? I asked Mom how late he could be and still get us. “It’s his weekend.” From her face, I could tell she wished she had a better answer to give me. I understood then that I could never stop worrying.

We’d moved into a house my grandparents rented for us, so my sisters and I changed schools in the middle of the year for the second year in a row. At least this time we were still in the same district and would be taught the same curriculum, which sounded great in theory. In practice, I had to put on the same second-grade play at my new school that I already performed at my old one: The Lion & The Mouse. Though I knew there was no getting out of it, I was determined to memorize and deliver a different line this time around. I mustered the courage I believed a lion to have and met my new teacher at her desk. “Can I have any part other than hunter #3?” She made me the mouse.

This surprised everyone, me most of all. I was shy and spoke so quietly I’d been held back in preschool. I almost asked if I could switch to hunter #1 or hunter #2. But even though I lacked vocal projection, I had a lot of experience being a mouse. I’d been pretending I was an animal since I was 3, stuffing my blanket into my pants as a tail, wearing various plastic noses, and running around on all fours so much I developed a large cyst on the top of my wrist. If anyone could play a mouse authentically, I was sure it was me. On stage, I gnawed the netted lion free.

At home, I was having nightmares. I saw the face of Medusa. Green skin, glowing eyes. I didn’t meet her gaze. Not because I feared her piercing stare turning me to stone, but because I was transfixed by her hair of writhing snakes. They didn’t scare me. They disgusted me. The thick girth of their bodies where thin strands of hair should have been made my fingers jump. I reached out and grabbed hold of one and pulled it loose. The snake detached from her skull with the sound of smacking lips. I discarded the creature whose corpse ended abruptly in strange flatness. On Medusa’s head, hair sprouted from the spot, as though the strands were contained fully grown within the snake’s body. I pulled another. And another, until there were no snakes left. I’d pulled them all.

I awoke and rushed to the bathroom to check my own hair. Brushing it back, I could see the bald patch above my right ear hadn’t grown any bigger, but standing in front of the mirror, I felt the urge to make it. My fingers searched for the thickest, darkest, roughest hair and removed it. Over and over again. There was always another strand that irritated. At some point, the scrape of my nail or an overly aggressive yank caused my skin to bleed and I panicked. Blood was supposed to stay inside.

In the morning, when I showed Mom the scab so she could assure me I wouldn’t die, she was horrified. She signed me up for therapy. I begged her not to tell Dad. The next time he showed up for visitation, the first thing he said was, “How is your hair?” I shot Mom a scathing look of disbelief as I followed Dad out the door.

I began therapy with a lot of trust issues and with Leftie, my Beanie Baby donkey, complete with a hand-crafted bridle made of string. Though my therapist, with his white hair and face like Einstein’s, fit my expectations, nothing else did. His office felt more like a living room than a clinic. Rather than reclining on some futon, I sat on the floor in front of his fireplace. When he spoke, his voice was quiet. When I spoke, mine was quieter. But neither of us said much. Rather than talking, we drew.

He sketched two hills separated by a valley in the middle. A Billy goat perched on each peak. The story he told didn’t have a troll or a bridge or even a plot, so I didn’t think it really counted as a story, but in its telling I realized the point of the exercise. It was obvious the picture and story were an analogy for my family. It felt pedantic even if I didn’t have the word for it then. I decided to tell a story that had no connection to my situation. I drew mice. I had some experience since for my kindergarten self-portrait I’d included a mouse nose and whiskers. When the therapist asked for my story, I explained the mice’s parents were dead, so the oldest mouse was left to care for the younger mice siblings, venturing out from the safety of the burrow to search for food.

WILD HORSES COULDN’T DRAG ME AWAY

After horseback riding camp, I became obsessed with Bob. For Christmas that year, I got a Breyer horse named Freedom that looked just like him and a model stall customized with Bob’s name on it. As much as I wanted to, I never rode Bob again. I only pretended he was mine. Mom enrolled me in weekly horseback riding lessons at a stable closer and more affordable than his. I learned that to fall in love with one horse is to fall in love with them all. Slowly I stopped pulling out my hair.

When I wasn’t riding horses, I was reading about them. Mom taught me to love books, often reading aloud to my sisters and me before bed. She opened the door to Narnia this way, and once through, I saw no reason to leave. I discovered something in C.S. Lewis’s novel The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe that I would search for in other books afterward. It was a story of unconditional love. The lion—Aslan—disappeared but always returned, died on a stone table but came back even then.

Mom frequently took us to the local library for free fun. We could spend a whole afternoon there. In the children’s section, she’d read stories aloud to my youngest sister while we two older siblings looked around. I discovered a section dedicated to horses and shelves of authors who wrote novels about them. In Walter Farley’s series, I encountered Shetan, the same black stallion whom I’d first seen on screen. I met Misty, the island pony, and Sham, the Godolphin Arabian, in Marguerite Henry’s tales. When I ran out of novels about horses and the people they carried, I turned to nonfiction where I learned about the language of horses and the language of memoir. I read everything the library had, and I came to understand something that I knew most of the adults in my life couldn’t.

Visiting Dad was something I no longer wanted to do, and I started saying so. I had homework and friends and hobbies, and I was tired of waiting. I told Mom, she told Dad, and I didn’t have to go with him that weekend. Or the next weekend I was supposed to. Or the one after that. However, as I’d already learned, nothing but “gone” is forever, and eventually, Dad wasn’t having it. He suspected Mom was behind the shenanigans, so then I had to tell him myself each time I didn’t want to go. Dad had a way of looking hurt that made me feel guilty, but that guilt just didn’t weigh as much as the pain and anxiety.

Dad let me say no a couple of times until one Friday I said “no” and he told me to get in the car anyway. On the thirty-minute drive to his apartment, I stared out the window the entire way, and I saw a black horse galloping beside us. He leapt fences and wove in and out of trees. His eye never left me. I closed my own eyes and reached through the window, grabbed ahold of his long mane, and swung onto his back. I wanted to ride away, ride home, but we couldn’t change course, so I rode him all the way to Dad’s apartment. It felt good to be out of the car.

After that, my “no” didn’t seem to ever count. I rode the black horse to Dad’s apartment on Friday and then back home on Sunday. At night I dreamed I became the dark horse. I opened the door to the apartment and my body morphed into an animal that could fly without wings.

During the day, I was there and not there. Since I realized I wouldn’t be rescued, part of me was always plotting an escape. Finally, one Friday I refused to get in the car even after Dad said he wasn’t going to let me say “no” this time. I told him I wasn’t coming and went back inside the house. He called the police.

When the cruiser pulled up, I asked Mom if I was going to be arrested. She tried to laugh through the stress and assured me I would not go to jail. “Then will the policemen make me go with him?” She didn’t think they could. But they did.

The officer told me I had to get in Dad’s car. I assumed the “or else?” was jail. I wasn’t worried about me anymore—I realized it was Mom they’d take. I rode the black horse to the apartment. After I rode him home, I steered him to court.

At 12 years old, I missed school to take the stand. Dad wanted Mom jailed. I wanted out. In the voice of a mouse, quiet but determined, I told the magistrate that I didn’t want to visit my dad anymore. The magistrate’s face was unreadable as I explained why and answered his questions. I worried he couldn’t hear me, or could but didn’t believe me, or did but didn’t care. In the end, I gnawed myself free.

WILD HORSES, WE’LL RIDE THEM SOMEDAY

Healing is a rare and wild thing.

The trauma of it all hid inside my body, though nothing can hide forever. In high school, I tried to escape it. I stayed in my basement bedroom listening to a CD of sad songs I’d burned. Sarah McLachlan’s “Angel.” Joni Mitchell’s “River.” The Sundays’ “Wild Horses.”

In Harriet Wheeler’s vocals I heard the desire to promise something that I suspected she could not. Forever. Still, her voice was more than honest—it was earnest. She pleaded not with the listener to believe her but with the wild universe to let it be true. To make leaving something we didn’t need to do. Because to leave is to leave behind, whether you want to or not, whether you’re being dragged away or carried. Even facing the inevitable, The Sundays’ cover insisted on an unapologetic hope, which was something I needed.

A doctor I didn’t want to see prescribed pills I didn’t want to take. When I stopped swallowing them, Mom took another approach. She put me back in weekly riding lessons after a two-year break. A month later I asked if I could use the money from my part-time job to pay for a second lesson each week. Several more months later, I asked for something bigger.

I wanted a horse.

I opened my notebook and laid out my plan. I’d researched and done the math: I had nearly $3,000 in savings, and I had just gotten another part-time job at the movie rental store, where I could make about $100 a week. In the newspaper’s classifieds, I’d found a co-op facility just fifteen minutes away where I could do barn chores in exchange for a reduced boarding fee.

Mom said no. It was too much money, too much work, too much could go wrong. Neither my calculations nor my promises nor my pleading changed her mind, so I retreated to my bedroom. A few hours later, she said she’d changed her mind.

I found him online. The drive from my home to his was nearly 300 miles. I said little the entire way, just clutched the directions printed off MapQuest, checking each step, reviewing our progress until we reached our last turn. As we arrived at Cooper Street, the houses sat too close together, sharing each other’s confidence with no room for yards, let alone pastures.

Mom slowed the car and pulled to the curb. She checked the street. It was right. We checked the GPS. It was right. I checked the directions. They were right. Then I pulled out the email I’d printed before we left to check the address. Cooper Road. I didn’t expect a town of little more than 1,000 people to have both a Cooper Road and a Cooper Street. We attempted to reprogram the GPS, but it couldn’t locate a Cooper Road. “What do we do now?” I asked. Out the window, I saw a pastor on a bicycle coasting toward us. He stopped at the passenger window and asked if we needed any help. I wondered what lost looked like.

The pastor directed us up the road and a little out of town. It wasn’t much further, he promised. He righted his bike as Mom restarted the car. I looked out the window to watch him go, but he’d already disappeared.

The woman wasted no time in leading us around to the barn. She disappeared into a stall at the very back and emerged with the black Arabian that until now I’d seen only in pictures online. Ali swiveled his head to look at me. His eye caught mine and I recognized it. I knew then—he was mine.

Ali arrived late in the night, and the blackness of his coat made him disappear into it. Not yet, not without me, I thought. I renamed him Aslan. In college, I would learn of the Christian allegory of Narnia. I’d also learn that in the Islamic faith, Ali was given the name Asadullah, which is Arabic for Lion of God. My horse, the lion and the lamb.

Finding Aslan was just the start, as it is with any horse story. I dragged him across the country with me to college, to my first job, to graduate school—Ohio to New Mexico to Colorado and finally back to Ohio. In the ways that count, though, he took me all those places.

The books I read as a kid taught me a horse could save a person, or they could save each other—or, perhaps more accurately, in saving a horse, a person could save herself. I didn’t rescue Aslan in the conventional sense. I found him and loved him. I don’t know if it was Aslan or the stories I believed about him that saved me in the end. I’d seen a love that could walk away, but Aslan has always found me. When he sees me or hears my voice, he ripples over the pasture like he is the wind itself. Bob showed me I could escape this world on the back of a horse. Aslan made it so I didn’t need to.

Morgan Riedl is a doctoral student at Ohio University in Athens, where she lives with her partner and her retired horse (not in the house). She has an MA in creative nonfiction from Colorado State University. Her essays have been featured in The Normal School, Sonora Review, and Entropy, and her poetry is forthcoming in Thin Air.