round 2

(6) CONCRETE BLONDE, “EVERYBODY KNOWS”

dragged up

(14) mountain goats, “the sign”

195-142

and will play on in the sweet 16

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/11/22.

SRH (SERIOUSLY REVOLUTIONARY HANDBILL!): KARLEIGH FRISBIE BROGAN ON CONCRETE BLONDE’S COVER OF LEONARD COHEN’S “EVERYBODY KNOWS”

Erica and I pretend-smoked beneath the UA 5 theater’s marquee. It was a warm night, typical for September, but I wore the noisy, stiff leather jacket anyway. It was glossy black and smelled faintly of cigs and Exclamation—left behind at my dad’s apartment by one of his dates. It made me feel badass, like I was the Samantha Mathis character. The “eat-me beat-me lady.” Erica called it my Michael Jackson jacket, which annoyed me because it was way more goth than King of Pop. We wore the matching dog tag necklaces we got at Contempo, almost-black lipstick, and lots of crushed velvet and stretchy lace. We were fourteen-almost-fifteen, new best friends in a new decade. The year before: Germans cheered atop a graffitied wall, Dana Carvey became president, ducks and sea otters got smothered in oil, and I crouched with my family under the kitchen table as our house rattled and swayed in the Loma Prieta earthquake.

The movie we were about to see was Allan Moyle’s 1990 teen drama, Pump Up the Volume. It would be my second time, Erica’s fourth. We were totally obsessed, went to see it tons that fall, even followed it to the cheapo theater one town over. Erica snuck a bulky tape recorder that required a week’s allowance-worth of D batteries in under her coat and recorded the entire thing so we could listen to it as we fell asleep at night, memorizing Hard Harry’s pervy catchphrases. Also on cassette: the soundtrack I took with me everywhere. I bought it at Wherehouse Records with the ten-dollar bill I got in a trick-or-treat card from Grams. The nubs on its case were already busted off, its magnetic tape stretched thin from so much play. Though its cover art was budget—featuring a grainy still of Christian Slater’s Mark Hunter in purple monochrome—its content was invaluable, an abridged primer on cool. But thirty-some-odd years later I realize it wasn’t the Pixies or Sonic Youth tracks, wasn’t Bad Brains doing MC5, the early Soundgarden, or the solo Peter Murphy, nor was it the Eazy-E g-funk protégés Above the Law sampling James Brown by way of Vicki Anderson’s Black feminist anthem “The Message from the Soul Sisters.” No. It was Concrete Blonde’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows” that altered me.

The first time I heard it, I was confused. Pissed, even. I’d expected the version I knew from the film—the preset drum-machine beat, the creepy synthesized strings, the seemingly out-of-place Spanish guitar and, mostly, Cohen’s startling voice, so deep and sure, chilled with a smiling cynicism. This one had a different tune, tempo, and singer. Instead of giving me goosebumps it gave me anxiety.

At the time, I was only sort-of familiar with Concrete Blonde. Their hit, “Joey,” was gateway, broke me from bubblegum. It was Johnette Napolitano’s husky rasp, her matte black hair, bangs that voided her eyes and made her mouth big. It was that she didn’t have her own drugstore perfume, didn’t perform in front of Miller’s Outpost. The video played at least twice a day after school, and I watched, rapt. For all the song’s impact, however, it had been the only one of theirs I knew. Maybe I was a few grades too young. They were the kind of band that kids my age with older sisters were into. The same girls who listened to Sinéad O’Connor and R.E.M. when I was still Debbie Gibson and Tiffany all the way.

Concrete Blonde’s sound was a little Anne Rice-novel goth, a little LA sleaze rock, a little Brigade-era Heart. The production value was clean and commercial, even on their decidedly more punk tracks. It was precisely because of their blend of pop accessibility and underground cachet that they were commissioned to cover Cohen’s song for Pump Up the Volume. Moyle wanted the original but New Line Cinema’s Bob Shaye thought it too gloomy and old-man. In the end, both got their way: The Cohen original plays in diegesis throughout the film, Hard Harry’s theme song with which he opens his nightly broadcast; the chorus of Concrete Blonde’s cover is used at the film’s climax—a mere 26 seconds toward the end of the film. It’s a variation on a theme, the octave-up belt from a big-lunged contralto as the hero and his love interest drive off, clumsily, into the night.

In this version, guitars shimmer, emitting the fading warmth of a sunset—a desert sunset, specifically, the kind that yields to windy, bitter, starlit cold. Though the beat is slower—exactly the pace of walking across campus to fifth-period French, head down, hair in eyes—Napolitano burns through the verses more quickly, as if to avoid sitting with their implications. Unlike the detached, disheartened, and droll vocals of Cohen, Napolitano’s are impassioned and mournful. There’s just the slightest hint of tremble in her voice—from exhaustion, it seems. Or fear. Or maybe the vice with which to cope.

The lyrics were written by Cohen and his back-up singer-cum-artistic collaborator, Sharon Robinson. The message: everything’s fucked. The song’s a dark and defeatist commentary on the status quo, referencing class struggle, racism, corruption, infidelity, and plague. “The poor stay poor and the rich get rich, that’s how it goes,” is how it goes.

At 15, I didn’t get all the innuendos. I frequently misheard them, collapsing their meanings. It’s dice that are loaded, not days—though mine most certainly were, with homework and chores and the preps giving me dirty looks. I knew the song was bleak, but I couldn’t yet map it onto the safe, suburban, wall-to-wall carpeted world I was familiar with. Teachers sucked and so did parents (except for Erica’s). Cops were pigs who’d put me in jail for the pinch of schwag in my backpack. Politicians wore powdered wigs and had wooden teeth. That’s really all I knew.

The song, either version, worked perfectly with the movie’s plot. Super quick: it’s about a quiet teenage loner, the aforementioned Mark Hunter, who, by night, adopts the alter-ego of Happy Harry Hard-on (a.k.a. Hard Harry)—a disgruntled, sardonic insurrectionist, a horny, onanist Ann Landers, and a deejay of very cool music—and airs a pirate radio station from the basement of his parents’ home. His message, like the song itself, is that everything’s fucked. “Everything’s polluted,” he says, ripping off the polite-maniacal delivery of Jack Nicholson, “the environment, the government, the schools, you name it.” His censure of authority, establishment, guidance counselors, even his dad are general and sweeping—bumper sticker imperatives that foment unrest and excitement in every puby adolescent in his fictional Arizona burb, uniting jocks and stoners and punks and princesses alike. Teens revolt, school admin and city-council-meeting moms quake in their footwear, feds get involved, corruption is exposed, sexy scene, chase scene, call to action, end.

The movie’s driving concern is freedom of speech. Happy Harry Hard-on’s shorthand for the First Amendment is “talk hard,” and his devotees spray paint it all over campus. At the end of the film, right after Hard Harry is hauled away by police and just before the credits roll, we hear a sound collage of young voices announcing their call letters and dial designations into the ether. It’s the promise of a polyvocal, youth-driven future.

I didn’t look too hard at the character of Mark/ Harry back then. I thought he was hot with his widow’s peak, his bowling shirt, and his cigarette. His oh-so-deep-sounding monologue that ribboned through the film’s hour and forty-five. I failed to see his (possibly unintended) hypocrisies. Unable to connect with people in real life, Mark dons a persona and uses technology to reach out to a worshipping audience. But, just like his penchant to compulsively jack off (also just an act), his radio show is, to him anyway, masturbatory. He has convinced himself that he’s only screaming into the void, eschewing the vulnerability and accountability that come with actual human relationships. When he sees evidence that swaths of people have been impacted by his words, he’s made uncomfortable. At one point, after he implores his listeners to “go crazy,” and they, indeed, do, he regrets his words, acting as if he never meant them. “This is out of control,” he says, cowering behind a pillar. “This whole thing is making me ill.”

It’s ironic—or genius—that Mark/Harry, though furious with the status quo and successful in upsetting it to some degree, when confronted with his influence, wishes, if only momentarily, to maintain said status quo. To be yet another verse in his beloved song. He had underestimated the power of his voice, the disruption and unfamiliarity it was capable of ushering in, this voice that no longer needed him at all.

His cat-got tongue, his swimmy tum, not evidence of poseurdom but of, by my read, fear. It’s possible he knew his identity would soon be revealed and, socially awkward shadow dweller that he was, was afraid to be seen. I’m reminded of a 1977 Audre Lorde essay: She explains our reasons for staying silent when we need to speak out are varied—fearing everything from pillory to glory. “But most of all, I think,” she says, “we fear the visibility.”

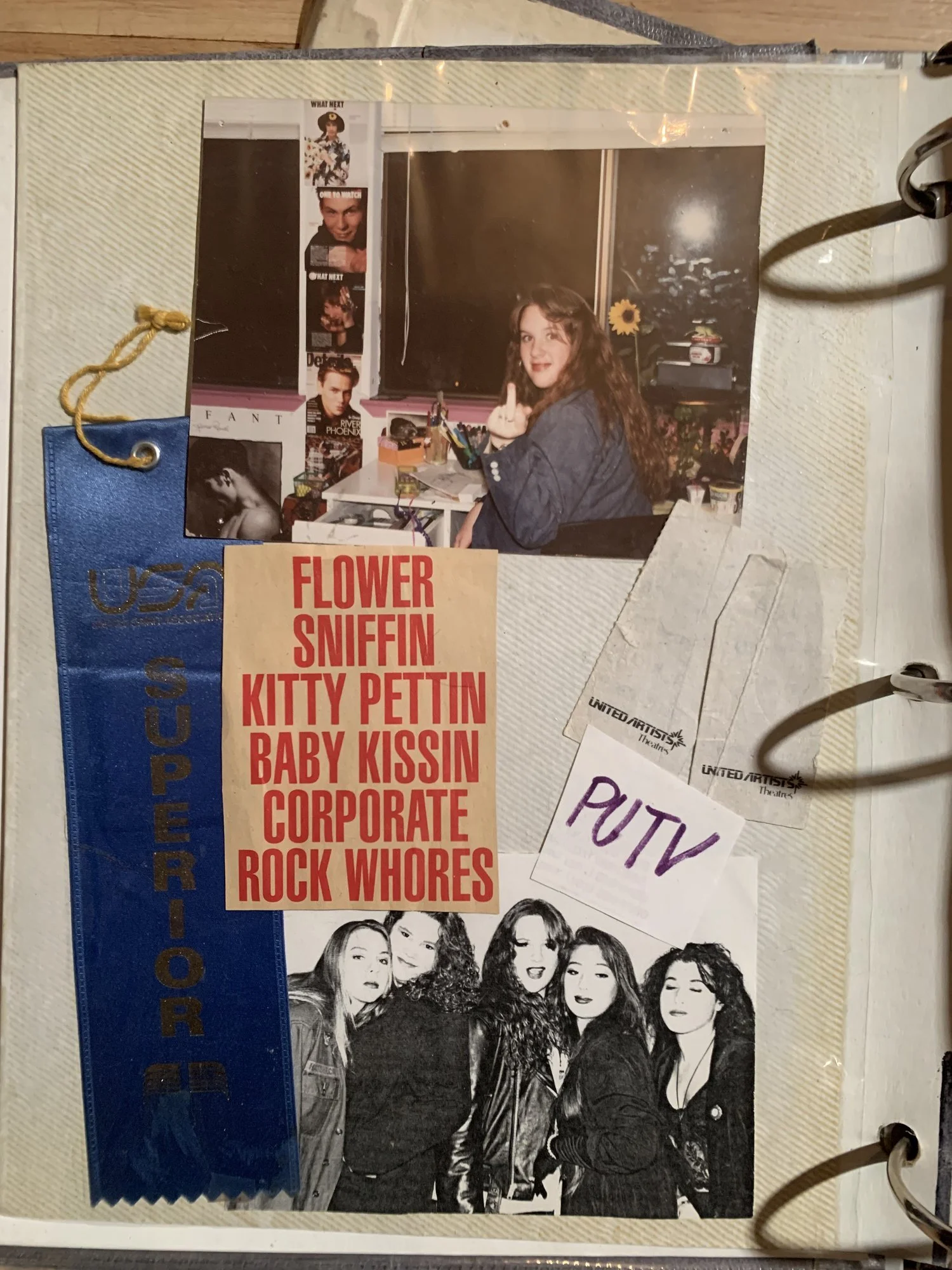

When I watched the movie those fall nights long ago, amidst the smell of fake butter and real leather I, too, wanted to rise up and vandalize school property, blow up my kitchen, kick over a garbage can, talk hard. I was fed up! With what, I’m not entirely sure. But it wasn’t hormones. Or a fad. How I hated those explain-aways. I was a teenager who, like all teenagers, was experiencing the cold-water shock of having my boat, the one I had been in since birth, the one I trusted to keep me safe, tip over again and again. This was called learning. I was not yet at the place where the grown-ups were, back inside it, afraid to rock it, as the expression goes. I had integrated the woes of the world osmotically, inherited their memories genetically, could not articulate what they were exactly, but felt them banging inside of me. This was before I was taught to forget my anger, before I learned to sit still in my boat. Itchy and optimistic, Erica and I decided to start an underground paper. We named it SRH, our high school’s monogram and a nod to HHH—Hubert Humphrey High, the fictional school that loaned Happy Harry Hard-on his initials. I won’t disclose what we made SRH stand for because it’s way too cringey. I’ll admit we consulted a thesaurus.

Our paper was a tabloid-sized sheet, double-sided, handwritten, printed at Kinko’s with the money I had collected for cheer squad candy bar sales. Screw cheer. The paper criticized society, pointed out injustices, mocked the popular kids, gossiped about teachers, and dog-whistled references to cool music and drugs. We hoped to witness students passing around our anonymous broadside, mouths agape. To hear warnings over the morning bulletin that its authors, if found, would face suspension, expulsion even. To start some kind of revolution. I remember arriving on campus before zero period to distribute the paper. We left copies on desks, shoved them into locker vents, piled them atop The Santa Rosan. Then waited. In Mr. Hegerhorst’s geometry class, kids brushed them onto the floor with nary a glance. After school, a few blew around in the quad, covered in footprints. A stack of them looked up at me from a garbage can. It wasn’t until the next day I finally saw someone reading it. A quiet loner whose name I didn’t know. A Mark Hunter. I smiled. Just one person was all I needed to see.

Truth was, that no one gave two figs about our paper only supported the song’s sentiment. See? I thought then. Shit’s fucked. And the song isn’t just saying that shit’s fucked. It’s saying that shit’s fucked despite how it appears or what we tell ourselves. What looks fair is rigged. What seems stable is precarious. What claims to be progress is, often, just maintenance. Emancipation, Brown v. Board, the civil rights act—but still, as the song goes: “Old Black Joe’s still picking cotton for your ribbons and bows.”

I’d pop my tape into my turquoise boombox, scrub it back to the beginning, and plop onto my top-bunk bed in the room I shared with two sisters, a damp room with pink walls covered in heavy-metal posters and black mold. That first crack of the snare and glimmer of the guitar became the sound of my ache. I let Johnette’s voice superimpose my own, let it speak for me in ways I didn’t yet have the courage to. The Cohen version would never have worked for me. Both songs may have been saying the same exact thing but their emotional content differed. One was nihilistic, closed off, and Kelvin-cold, the other doleful yet resilient and expansive. One made me denounce God and the other made yearn for him. One made me want to give up while the other made me want to give.

I recently watched a live recording of Johnette performing “Everybody Knows” for MTV’s 120 Minutes in 1997. She’s accompanied by a single acoustic guitar. Floats in a long, pale dress. Her eyes switch from spooked to somber and back again. Her voice is somehow both wispy and rich, tough and frail. She’s old by music industry standards—just turned forty—but still displays the bruises of youth. Still moans like it’s her first hurt.

And here I am now, almost seven years older than she is in the recording. I, too, feel new in many ways. I am learning that silence is complicity. Is violence. Is not a virtue. Not golden. I am learning that I can learn from young people, from whence their rebellion and activism meets. I am learning not to sit still in my boat no matter how tired I am. No matter how nice or how crappy my boat is. It seems we’re at a time when things couldn’t possibly be more fucked. I won’t even list examples of the fuckery because it just makes me, and you, even more tired. Because everybody knows already.

Karleigh Frisbie Brogan is a writer from Sonoma County, California who currently resides in Portland, Oregon. Her writing has been published in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Huffington Post, Entropy, Nailed, Lana Turner, Water~Stone Review, and elsewhere. She is an editor at Kithe and the wine person at your favorite store. Find her writing at karleighfrisbiebrogan.com and on Twitter @FrisbieKarleigh.

DUSTIN luke nelson on the mountain goats’ “the sign”

Welcome to my Geocities website. Like a song, it is has a permanent aspect—the site you see now or the song as you hear it— and is always under construction, revised regularly, and re-interpreted by the creator, by its audience.

THIS PAGE IS HOSTED BY GEOCITIES GET YOUR OWN FREE HOME PAGE

A Note from the WebMaster

Covers serve a lot of purposes. They’re, at their molten core, a tribute. Tributes come in many forms, but they’re a way to welcome others to engage in a communal appreciation.

A cover is easy. You can take the guitar from the basement off its decorative stand and play “Wonderwall.” That’s a cover. A great cover, however, takes that tribute, that interpretation to another place. It’s not a facsimile. It’s the creation of something new with the materials provided. Here, you can almost imagine the process that goes from John Darnielle, the engine behind the Mountain Goats, grabbing a guitar to fool around with “The Sign,” smiling. Moving from that moment to the moment where he invites you to commune with his interpretation, with the Swedish quartet’s mega-hit that has largely been banished to that great pop station in the sky.

My Mind

The Mountain Goats released a cover of “The Sign” on 1999’s Bitter Melon Farm. Though, it’s always been more of a live song for the band. Darnielle said as much on CBC radio interview more than 15 years ago, calling it “a concert piece.” It makes the cover all that much greater because a tribute is about community. And like most tributes to music—zines, articles, sing-alongs, Geocities fan pages—there is something necessarily, beautifully impermanent about that feeling. To be there in that moment, to hard code a tribute to your favorite band on a site that will disappear into the ether as though it never existed someday in the future, to sing along to a song that will end. It’s a sacred interaction, a sacred dialogue.

Geocities, an early standard-bearer of fan-run websites for bands, books, and art, started up in 1994, months after the November 1993 release of “The Sign.” It opened its digital doors to “under construction” GIFs in the same year, 1994, that “The Sign” reached number one on Billboard’s year-end chart. Three songs of the album The Sign made the top ten at the end of the year. “All That She Wants" came in at #9 and “Don’t Turn Around” came in at #10. If you loved Ace of Base you could sing along to their constant presence on the radio, write a cover like The Mountain Goats, or make a Geocities site to show your love

Young and Proud

Darnielle was 27 when “The Sign” was charting. (At least, that’s what another fan-edited site asserts.) There are plenty of memorable pop songs from that year. The Swedish group was competing for airtime with Elton John (“Can You Feel the Love Tonight?”), Madonna (“I’ll Remember”), Janet Jackson (“Again”), Mariah Carey (“Hero), Celine Dion (“The Power of Love”), Boyz II Men (“I’ll Make Love to You”), and the Three Musketeers-inspired collaboration between Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart, and Sting (“All For Love”).

I was nine at the time. But I had an affinity for this song as well. It was something new. To a young person in love with punk and metal who also secretly loved pop music, there was something alluring about a new band. There was a maybe subconscious fear that if you told your friends you liked the new song by Elton John, Madonna, Janet Jackson, or Bryan Adams that there would be derision. “Madonna? No time for that. Punk in Drublic just came out. Let’s get your brother to take us to the Sam Goody at the mall after school!” “That’s perfect! Been meaning to stop by Hot Topic. They’ve got a sweet Question the Answers poster.”

A new band? You were writing the experience as it happened. There was a sort of blank canvas that you brought to an album, song, or cassingle. As Darnielle told the CBC, “No one would admit that they liked it, but I knew they did.”

Don’t Turn Around

A new band—or a band new to people I knew/the US—didn’t carry that kind of weight. There’s mystery. At a time when the internet was barely in existence, when you could have read the entire internet in a day, the collective ruling hadn’t come in if a band wasn’t regularly on the radio yet or hadn’t appeared in this month’s issue of Rolling Stone, Spin, or Guitar World.

The ruling would come in. It always does. Right or wrong.

However, by the time the collective ruling came in, I’d usually already made up my mind. It was just then a matter of how those social pressures influenced me. Did I like the song in secret? Did I take a stand? (Not hardly ever.) Did I try to convince my fledgling middle school ska band to cover Sugar Ray? (I tried.) But that didn’t drive a communal experience. I was lukewarm on “The Sign.” It was catchy. There was something there. But I didn’t love it. I didn’t have it on repeat.

Living in Danger

That’s where the work of a cover brings us full circle. Music is processed differently now—whether it’s how we listen to albums, where we get them, how we find out about it, et al—but the work of a cover isn’t entirely different now than it was in 1994 or 1999. It’s a tribute. It’s an interpretation. It’s an aural fan page. It’s an opportunity to build a communal experience through song and through literal community.

Voulez-Vous danser

This is all prelude to the real point of this fan page: The Mountain Goats’ cover of Ace of Base’s “The Sign” is the apotheosis of what a cover can do.

WHAT CAN A COVER DO!? (A non-exhaustive list of thoughts)

- Sometimes it’s The Hold Steady covering Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City.”

- You know or would have guessed that the band loves the artist they’re covering. They wear the influence on their sleeve. It’s passionate. It’s a love letter. It can be good. It ultimately does not reinvent the wheel. It’s a tribute. It’s rarely a profound listening experience, though. That’s subjective as hell. Still, it’s not a reinvention. It’s a tweaked facsimile.

- Sometimes it’s Bruce Springsteen covering Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream.”

- It can be a reappraisal. A metal band covering a pop song. A Springsteen-level musician covering a no wave band. It can be a joyous and unexpected combination. You may have never paired this artist with this song, but it’s loving.

- Sometimes it’s Goldfinger covering “The Thong Song.”

- Sometimes it’s basically #2, but it isn’t as much a love letter as an artist having fun. I saw Goldfinger cover “The Thong Song” at a festival more than two decades ago. If my failing memory serves, I never once got the impression that they thought they were covering a great song. They were having fun. They were surprising expectations. But there was a layer of non-confrontational cynicism in it.

- Sometimes it’s The Mountain Goats cover “The Sign.”

- Sometimes it’s a combination of these things.

Mr. Ace

Not all covers are tributes. Not all covers have a desire to build a communal experience. When The Mountain Goats cover “The Sign,” it’s a reappraisal. It feels full of love. It says, ‘Listen up. This song? This song is better than you remember. Did you dismiss it when it came on Z100 in 1994? That was your mistake. We’re going to kill it, but also want to give you a new perspective on what this song can accomplish. We are going to open up your eyes when you hear “The Sign.”’

A good cover in this vein tells a joyous story about the myriad ways that music impacts life through the connections it builds. But when John Darnielle covers “The Sign” that joyous feeling hits another level devoid of cynicism that sometimes accompanies an indie band covering a pop song. A room full of people there to see The Mountain Goats along with a tour mate like Lydia Loveless or Loamlands or Nurses or Megafaun, they’re now singing along, maybe laughing at a story told about how this resplendent cover has a history in their own lives, that people have doubted its greatness and he has long evangelized for this song.

The Sign

For a not insignificant number of people, Ace of Base has been easy to forget. Darnielle knows—whether or not that’s explicit or implicit— that a cover like this involves community. It lives for the relationship between artist and audience. There is joy. There is memory. There is an experience that is being shared. Also, the cover is pretty fucking good.

That might all make a great cover sound easy, but Darnielle invites everyone to participate. That’s not as easy. It needs love. But it also thrives because he’s willing to be tongue-in-cheek as well. That’s borne of a dismissiveness of the original song, but because it’s a catchy song. Saying “this is fun” rather than ”this is holy” opens the door for everyone to participate in the moment. It’s a Rorschach test with no wrong answer.

“The Sign,” as a cover, elevates the song—with respect to the original songwriters—from something you forgot to something you are reconsidering. It’s Proust’s madeleine if you hated madeleines and forgot they existed until you had one again years later and it totally fucking shook up your shit.

Dustin Luke Nelson writes comics and stories and lives in Minneapolis and has seen The Mountain Goats so many times. He wrote the poetry collection "in the office hours of the polar vortex" and has had poetry in Best American Experimental Writing, Fence, Nervous Breakdown, and elsewhere. His non-fiction has appeared at Thrillist, Rolling Stone, Sports Illustrated, the Walker Reader, Men's Journal, Tiny Mix Tapes, The Hockey News, and elsewhere.