sound and vision, signifying nothing

cheryl graham on THE HUNGER

Just after punk morphed into New Wave, and before the Jack Daniels-soaked abomination of hair metal reared its Aqua-Netted head, there was a promise of a better day. It was a time when we thought the self-indulgence of the 70’s would finally be killed by a dagger through the heart at the hand of the cool modernism of the 80’s, and nowhere did that promise shine more brightly (or darkly, as it were) than in The Hunger, Tony Scott’s 1983 gothic horror movie.

In particular, The Hunger’s opening sequence served up an erotically-charged fantasy of urban sophistication, where the people were hot, the palette was cool, and the music was a secret language by which its devotees staked their identities along tribal lines.

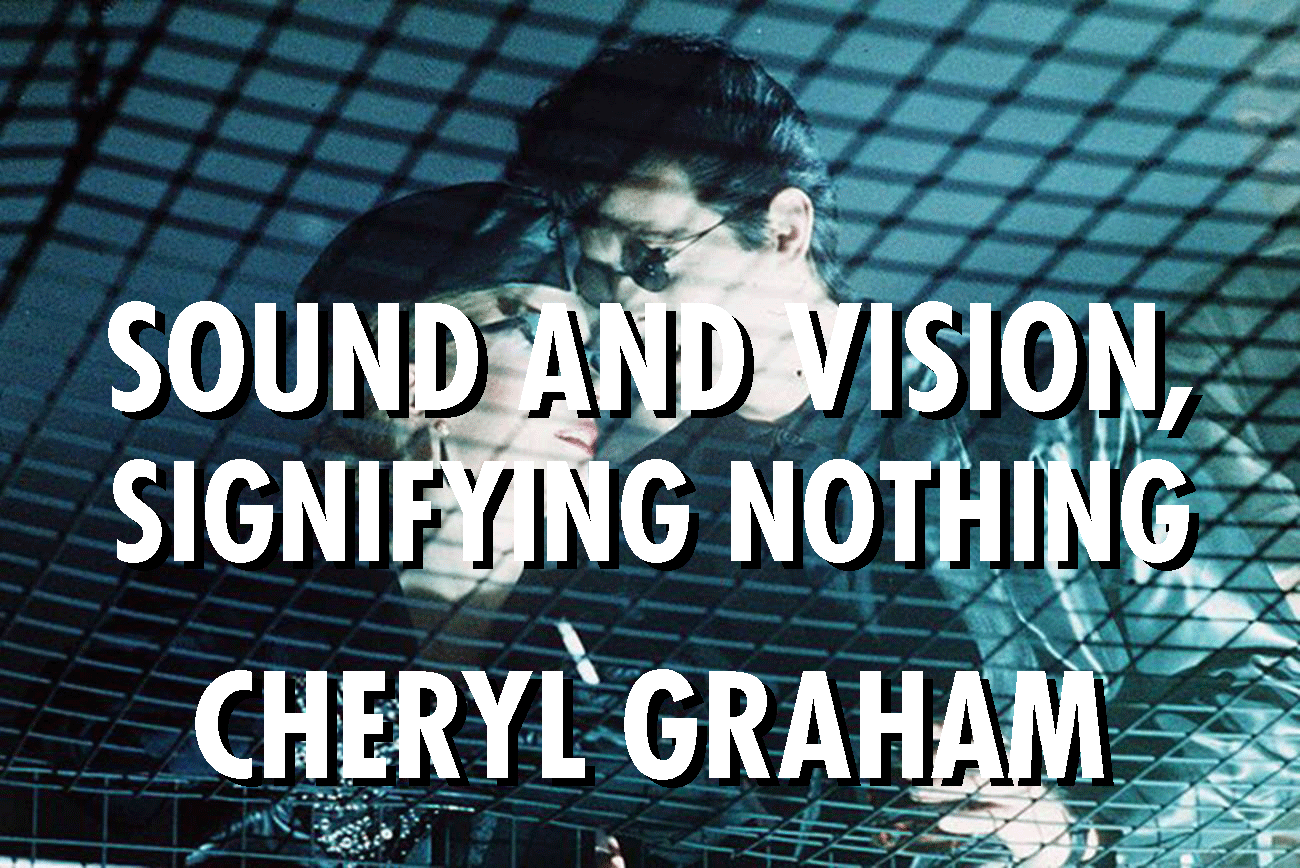

The credits roll to the industrial percussion and animalistic feedback of Bauhaus’ “Bela Lugosi’s Dead,” heard by many Americans for the first time, four years after its release, in this very scene. Silhouetted against misty blue spotlights, Peter Murphy writhes and vamps behind a wire fence like a specter, his cheekbones arriving a beat ahead of him through the fog.

Interspersed with Murphy’s dark entries, the names of the three principals flash on screen: Catherine Deneuve. David Bowie. Susan Sarandon.

The camera pulls back briefly on a subterranean nightclub crowd, then cuts to the blood red lips, sunglasses, and cigarette of Miriam Blalock, played by Deneuve. She and her suave companion (Bowie in a black wig) scale the stairs above the dance floor, surveying the throbbing crowd like appraisers at a cattle auction. They train their predatory gaze on a punky couple dancing, and after a few cruise-y looks between John and the male half of the duo (the first indication of the fluid sexuality to come) he confers with Miriam, and the rest of the evening falls into place.

Murphy’s performance here refers back to Bauhaus’s interpretation of Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust.” In the video for their cover song, Murphy fonts the band inside a dark catacomb as desperate punks clamor to get closer to the stage. Jump-cuts of Murphy raging feral inside a wire cage are laced throughout the performance. From a distance, all spiky hair and skinny torso, he looks like Bowie on stage. Bowie, in The Hunger’s opening scene, with his black hair and light skin, bears a resemblance to Murphy. Bowie playing Murphy playing Bowie: It’s an infinite loop of 80’s post modernism.

In the next shot, the Blaylocks’ black town car glides along the Long Island Expressway in the pre-dawn light (this utopian gothic disco is evidently somewhere near Bay Shore), headed for an afterparty of four at an undisclosed location. There, after a bit of salacious foreplay, cross-cut with more Peter Murphy, some ferocious murderous monkeys (don’t ask), and lots of smoking, John and Miriam whip out the tiny daggers concealed within their respective ankh pendants and proceed to drink their victims’ blood with performative abandon. In the morning they return to their uptown Manhattan mansion for another kind of feed, this time unceremoniously slinging the couple’s body-bagged corpses into the maw of the incinerator in the basement.

The Blaylocks, sophisticated, avant-garde, and impossibly cool (except maybe for their actual bloodlust) are uber Goths: pale of pallor, preoccupied with the past, and post sexual rigidity. Miriam Blaylock is a centuries-old vampire of sorts, whose forever young lover John (through flashbacks we discern that she picked him up sometime around the French revolution) begins to age. Rapidly. He was promised everlasting life, so this development is decidedly not okay. He seeks the advice of Dr. Sarah Roberts (Sarandon), a gerontologist who studies progeria, an accelerated aging disorder. Dr. Roberts’ signature character traits are smoking heavily and running her fingers through her hair with dramatic intensity, the frequency of which would make for a potentially lethal drinking game.

As John becomes more fearful and desperate, Miriam already has her sights set on his replacement, none other than the good doctor Roberts. But first she must say goodbye to John, who doesn’t technically expire, but is instead relegated to everlasting death inside a wooden box in the attic, alongside Miriam’s other undead exes from centuries past. (Though we gather that Miriam is of Egyptian origin, it’s not explained whether she U-Hauled all those coffins to New York, nor is it clear how she is physically able to carry John’s {admittedly frail} body up all those stairs. But by this point in the narrative, if you haven’t completely suspended disbelief, well, not even a drop of fresh vampire blood can save you.)

After John is summarily cast aside, Deneuve’s telepathic magnetism lures Sarah to the townhouse where, after a languorous serenade and a spilled glass of sherry, out come the diaphanous scarves that are the hallmark of cinematic sapphic seduction. Bodily fluids are exchanged (though perhaps not the ones you’re thinking of), after which, presumably, Sarah is afflicted with The Hunger (“presumably” being the operative word here, because any semblance of plot coherence at this juncture is about as viable as Mr. Lugosi himself).

Critics (male, duh) at the time predictably fixated on this scene, reducing the film to a “lesbian vampire movie.” While these seven-and-a-half minutes of celluloid vaulted Deneuve to lesbian icon status, the scene is about transfusion more than titillation, sacrifice more than seduction. Don’t get me wrong, it’s definitely sexy (c’mon, it’s Susan Sarandon and Catherine Deneuve), but it’s not the whole movie. Or—spoiler alert—maybe it is.

Stylish and sepulchral, with more than a hint of danger, The Hunger is a cinematic analog to the credos of Goth subculture. The film’s moody reflections on everlasting love are well served by Scott’s phantasmagoric style, but like Goth itself, the film falls apart in a hazy mess of set decoration over story, posturing over principle. The Hunger was a revelation in 1983, challenging the preconceptions of what the vampire genre looked and sounded like. Goth, too, was an invigorating provocation of the rapidly-changing status quo at the time, one that encouraged a mining of the past, rather than blind insistence on forward motion. But then it got stuck. Just like Miriam’s lovers, Goth seemed forced to live out its days in a state of suspended animation, mired in portentous self-parody, always looking backward, growing old without growing up.

Watching it again thirty-five years on, The Hunger provoked in me a heady mix of emotion. Along with a fair amount of eye rolling came a nostalgia for a future that never quite materialized. I first saw the film when it came out (a couple of years before I came out) and thrilled to the possibility that I might one day be seduced by a chain-smoking, piano playing, French-speaking ice queen, and that I too, with the right music, clothing, and dramatic lighting could blithely pick up hot strangers at the club. (Nothing about that fantasy has changed much over the years, tbh).

The Hunger’s tagline was “Nothing Human Loves Forever.” But despite being savaged by critics, and a disappointment at the box office, it is nevertheless loved as an enduring cult favorite. Perhaps that, too, is the fate of Goth. It started out so well, but for a culture obsessed with death and darkness, it stubbornly refuses to die. Or evolve. Once strange and shocking, Goth is now dismally earnest, self-serious, and a little bit silly. The bats have left the bell tower, the victims have been bled. Undead, undead, undead.

c. 1983. Me with my band the Phantom Limbs. (L-R: Jim Parks, Cheryl Graham, Jefferson Keenan)

Cheryl Graham is a child of the 80’s, but has a secret love of self-indulgent prog rock from the 70’s.