1.

There’s bad, and then there’s baaaad. This essay concerns the former.

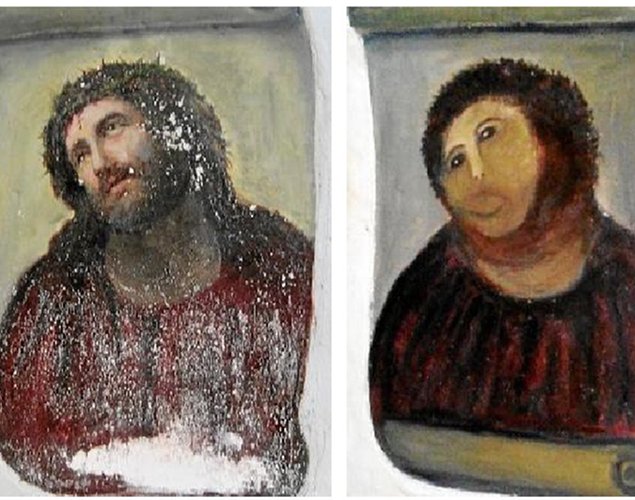

I have set as my phone’s screensaver the catastrophically baaaad restoration of “Ecce Homo,” by Cecelia Gimenez—a century-old fresco of Jesus Christ revisaged as monkey-faced Munch scream:

My girlfriend will attest that there is nothing in the world that has ever made me laugh harder than this painting, but also, I think, that there is nothing ironic about my love for it. It is, I insist with my whole heart, better in its restored state (if you can call it that) than the original—in this Gimenez and I are in complete agreement. For starters, who really needed one more fresco of Jesus looking like practically every previous painting of Jesus? The phony idea of what he is supposed to have looked like (if he even existed) repeated ad nauseum, I mean, what possible purpose does that serve that isn’t a cynical one? It is a near cousin to nihilism, this notion that value, much less holiness, can be conferred on so thoughtless and empty a gesture. Yet, at the same time, I must admit that my love of Gimenez’s contribution begins not with a thought of her consciously revisioning a new Christ for the ages, but instead discovering, in a kind of muted panic, as I imagine it, that whatever solvent she was using—in whatever concentration she’d deemed appropriate—had instantly and irreparably dissolved the previous image under her careful hand, turning it into a soupy gumbo of brown beard and white face pigments, into which she seems to have hastily, and with roughly the same lack of skill that I might apply, sketched a stick figure’s eyes and nose, and there, in place of a mouth, sort of more or less articulated the old line of beard and mustache into a yowling maw.

I mean to say that both of these are true—I see this painting as a colossal fuck-up and also as really great. It is (again, unlike the previous, unrestored version) wholly original, memorable, and singularly joyful. A mistake, maybe, but, more importantly, unmistakable. Not only is its path to greatness unbarred by its baaaadness, I would argue that, in order for anything to be truly great to this day and age—by which I mean profoundly relevant—it must risk a degree of baaadness. What else is Gimenez’s portrait, if not an infinitely more accurate depiction of our current world’s Prime Mover than those stately, noble and heroically tragic Christs of previous centuries? Our president is ten pounds of shit in a five-pound bag, our oceans are nearing the moment when they will have more plastic in them than fish. I wouldn’t know how to begin to explain the mess we’ve made to Jesus Christ. But Gimenez’s Savior understands.

2.

Hannah Gadsby hates Picasso; she thinks he’s bad.

This would be an instance of the first order of badness. Like baaaadness, there’s plenty in this category upon which, hopefully, we can all agree. Hitler is bad. Malaria is bad. Big Pharma, jingoism, crotch rot, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—you get the idea. Unlike its quirky cousin, there’s no delight to be had parsing out the details here. Fireworks appear only if we, like Gadsby, attempt to pry something commonly held to be “good” out of its privileged position and wrench it over to the malaria column. In effect to do this we have to perform a sinister variation on Gimenez’s task—we must deliberately approach the beloved object with the intention of ruining it. What separates our act from vandalism is that a vandal merely mars the surface of the object he or she assaults, whereas we are interested in literally de-facing ours. We want to remove what we see as a false exterior, in other words, and expose its rotten brain. Whereas the vandal devalues an established artifact by adding some unique flourish to the composition—a hastily scrawled penis, for instance—we are convinced that the valuation itself is in error, buttressed by some misplaced element which we have set about to eliminate. In a “reverse Gimenez,” if you will, it is as if we are denied a vision of the Savior and see only the yawning chasm.

I’ve been watching Gadsby’s Netflix special Nanette, in which she takes on this colossus of the art world because I’m looking for pointers as to how best to mount my own campaign against another deeply entrenched icon. In my case, it’s the John Lennon song, “Imagine.” I think it truly bad. What I’ve been struggling with, though, is what exactly it means to tell this to other people, many of whom, I understand, don’t just like, but love this thing. Why would anyone, for that matter, wish to expend good energy convincing others not to love something that they love? Yet I feel a commensurate urge to shout my hatred from the rooftops. Or, even better, like Gadsby, from the stage of the Sydney Opera House. And perhaps nowhere in her special do I feel a greater affinity with the comedian (anti-comedian?) than the moment immediately following her confessed Picasso hatred when she remarks, “but you’re not allowed to.”

This is a clearly paradoxical statement, yet it speaks to a deeper truth regarding the reverse Gimenez: it’s the protected status we perceive, shielding the object of our derision from an honest reckoning, that functions for us—the offended—as its “false face.” Even more than the object itself, this construction is what we object to and wish to dismantle. The image of Picasso as the twentieth century’s preeminent visual artist is emblematic for Gadsby of a canon which privileges genius above humanity. Whereas, if I’m honest, I must admit that it’s the sanctity afforded “Imagine,” more than its lyrical insipidness or soft-focus sound, that turns my stomach; the distinct impression that I am not allowed to say what I’m saying when I question its worth.

In Rolling Stone’s 2011 list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, “Imagine” is celebrated at number three as Lennon’s “greatest musical gift to the world.” The citation notes his song’s “serene melody; the pillowy chord progression; that beckoning four-note figure...and 22 lines of graceful, plain-spoken faith in the power of a world, united in purpose, to repair and change itself.” In his 1971 review of the titular album, however, Rolling Stone writer Ben Gerson described the track somewhat differently: “The singing is methodical but not really skilled, the melody undistinguished, except for the bridge, which sounds nice to me.” There’s no accounting for taste, of course, but what pleases me here isn’t just Gerson’s dismissal, it’s the fact that he’s responding to the song as it was released and not its long shadow. “From the shock of Lennon’s own death in 1980, to the unspeakable horror of September 11th,” the Rolling Stone citation concludes, “It is now impossible to imagine a world without ‘Imagine.’” While this may, in fact, be the case, I would counter that it’s become equally impossible to actually hear the thing.

The problem, to borrow a term from the wizarding world of Harry Potter, is that “Imagine” is no longer a song at all, it’s a horcrux. Like that talisman of dark magic, it contains both a fragment of spirit and resonant violence of the act which wrested it. The song now echoes with gunshots, even, apparently for some, the collapsing Twin Towers. And it’s precisely this darkness that lends the airy, insubstantial anthem any illusion of depth. Not only did it rise to its number one position (and longest occupancy) on the charts only after Lennon’s murder, but the profundity ascribed to it, as attested to by the bracketing tragedies in the above quote, coalesces in the wake of that heinous crime. “Imagine,” in other words, is a song reconstituted in Lennon’s assassination, belonging more to 1980 than ‘71. As such, it carries for its fawning adherents, I would suggest, a metaphorical heft, nowhere present within its verses. It has become a pair of blood-splattered spectacles; the moment when the self-professed Dreamer—and, by extension, the “dream” of sixties counter-culture revolution—fell resolutely at the feet of the Reagan years. It is now, in a sense, the site where many have chosen to bury John Lennon, and for whom criticism of it feels akin to desecrating his grave.

Recently, borrowing a page from Gadsby’s playbook, I told one similarly affronted fan, “You realize the John Lennon who sang ‘Imagine’ is the wife-beater, not the martyr, right?” This was a mistake, though not due to any issues of factual inaccuracy. In Lennon’s own words, “I was a hitter. I couldn’t express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women.” His physical abuse of first-wife, Cynthia Powell, has been well-documented. As has the assault which put The Cavern Club’s Bob Wooler into the hospital for insinuating homosexuality on Lennon’s part. At least as late as Lennon’s “lost weekend”—the eighteen months he spent estranged from Ono in 1973/‘74, a full two years after the recording of “Imagine,” the singer notably struggled with this troubling aspect of his personality, throwing a punch at a waitress in L.A.’s Troubadour nightclub, after an evening spent heckling the Smothers Brothers. On a separate occasion at the same club, he wore a Kotex on his head to an Ann Peebles concert.

Lennon is sort of the Hamlet of pop music—a figure routinely lauded for possessing the noblest of human virtues based upon almost no evidence of decent behavior on his part. All the while, sharing thoughts best kept to himself at full voice from the lip of the stage. He proclaimed his son Julian to be the product of a whiskey bottle, sang “baby, you’re a rich fag, Jew!” at manager Brian Epstein during a Beatles recording session, and confessed in the revelatory Playboy interview conducted shortly before his death that, contrary to the image he projected, he was a “most religious fellow” whose earlier politics and protest-singing was based largely on “guilt for being rich.” In his pro-capitalist, anti-evolution and increasingly isolationist rhetoric in that long conversation with journalist David Sheff, he comes across as a man whose personal ethics were dove-tailing nicely with the eighties, not some sacrificial lamb slaughtered on the altar of a new world order. “’I’m not going to get locked in that business of saving the world on stage,’ he tells Sheff, ‘the show is always a mess and the artist always comes off badly....’”

The mistake I admit to in employing Gadsby’s strategy here, as evidenced by my listener’s capsized expression, is that it’s not my intention to raze Lennon to the ground; it’s just the one song I’m after. I’m actually a fan of a lot of his work. Unlike Gadsby, I have no expectation that good art be made by good people. I’m as suspicious of her desire to replace the fifty thousand estimated works attributed to Picasso with one hack sketch of the artist, as I am of the Lennon fan’s need to recast their hero in the mold of his mooniest song, as some modern-day Prince of Peace. Both of these substitutions trade in that murky middle territory where badness meets baaaadness, and run-of-the-mill goodness runs up against her more angelic twin. I don’t question the ability of bad people to make good art. I question the Three Card Monty that seeks to swap-out aesthetic concerns for moral/ethical ones.

John Lennon himself played this game early and often with “Imagine,” variously trumpeting and bemoaning Phil Spector’s “sugar-coated” production as the chief reason why his song’s radical (“anti-religious, anti-nationalistic, anti-capitalistic, anti-conventional”) messaging was so easily absorbed by mainstream audiences. In an angry open letter to former bandmate Paul McCartney, published by Melody Maker magazine in December 1971, he lashed out, “So you think ‘Imagine’ ain’t political? It’s ‘Working Class Hero’ with sugar on it for conservatives like yourself!! Guess you didn’t dig the words. Imagine!”

All sarcasm aside, it really is worth trying to imagine this. Did Lennon mean to suggest that a song may contain politics in roughly the same way that a punchbowl can be laced with LSD? Can you truly slip potent, “anti-conventional” subtext to people in a 4/4 piano ballad written in C major? Or micky a song recorded, in Spector’s own words, “like the national anthem,” with a heady “anti-nationalistic” vibe? Which is to say nothing of the obvious irony in setting about to make an “anti-capitalistic” pop song. On the subject of the “Imagine” session, future murderer (if Lennon’s subsequent martyrdom has influence here, why shouldn’t his producer’s infamy, I figure) Spector remarked, “We knew it was going to be John making a political statement, but also a very commercial one.” Imagine that.

Generously I’d deem the song’s politics as aspirational as its lyrics. They are ideas of things he thought it would be good to try to do one day. Less generously, I’d suggest these are things he had no active interest in. Ever. Outside of his personal brand, that is. The man who sang “imagine no possessions” sang it on one of the two Steinway grands present on his estate at the time of the recording and died owning a fortune in cattle and a portfolio of houses. “Imagine” might be accurately described as the jingle of John Lennon Enterprises, a corporate interest which has been wildly successful at fusing these two entities—man and song—since 1972. The endeavor began that year with the made-for-tv movie, Imagine, and has continued through two documentaries—Imagine (1988) and Above Us Only Sky (2018)—as well as the Imagine Peace Tower, an art installation by Yoko Ono unveiled on Iceland’s Viðey Island in 2007, which projects a geothermally-fueled tower of light upwards of four thousand meters into the sky. The result is that “Imagine” has indeed achieved a degree of greatness, but it’s the greatness of scale—of coral reefs, cola wars and depressions. Even its most ardent fans don’t really consider it a good song; they consider it a song which performs Goodness. This is why they look at you, if you disparage it, like you’ve just punched a unicorn in the face. I can think of no other song which aligns itself to virtue in quite the same way.

Shortly before his death, Lennon conceded that “Imagine” owed much of its thematic content to Yoko Ono, adding, “Those days I was a bit more selfish, bit more macho, and I sort of omitted to mention her contribution.” In 2017, Ono was awarded a co-writing credit for the composition, but the fact remains that the John Lennon who sang the song couldn’t imagine sharing it.

That’s if we’re to believe his account. Personally, I think the real reason Lennon was reluctant to admit the collaboration is because his partner didn’t just pay lip service to anti- conventional thinking. Had he desired a truly radical song, Ono was the perfect co-pilot, not Spector. A one-time protégé of avant-garde composer, John Cage, and fervent collaborator with far-out musicians like Ornette Coleman and Charlie Haden, it was Yoko Ono who first introduced her husband to the musique concrète experiments that inspired “Revolution 9,” and who would continue, through Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band (1970), Fly (1974), and with singles, such as “Kiss Kiss Kiss,” from their Double Fantasy album (1980), to create the only truly disruptive, boundary-pushing music of the couple’s joint recording career. It seems likely that, beyond machismo, Lennon’s failure to acknowledge Ono’s co-ownership of “Imagine” at the time of its recording is because the ex-Beatle didn’t want an Ono/Lennon experiment, he wanted a hit.

He would end up with one, of course. One that would, in fits and starts, ultimately replace him—shooting beyond success even, to become the greatest song no one ever actually listens to. And perhaps this is why it’s so readily exchanged for a tombstone: “Imagine” resembles the sort of thing we’d etch into one, the nonsense said at funerals which doesn’t resemble the deceased at all.

For my part, I choose to bury John Lennon in the granite tomb that is “I Want You (She’s So Heavy).” Forced to select a peace anthem, it would be, hands down, “Instant Karma”—Instant karma’s gonna get you/ gonna knock you right on the head!—now there’s a line that smacks of some honesty.

The morning of December 9th, 1980, I was a nine-year-old sitting down to breakfast at our house in what was then the small town of Keller, Texas. I was only vaguely aware that something was amiss because uncharacteristically the radio on. The DJ was playing “Come Together” and I recall the contrast between my excitement at hearing rock-and-roll at the breakfast table—along with that song’s wildly elastic energy—and my parents’ downcast faces and slower-than-usual movement. The gunshots, for me, are there, but so is John Lennon’s humor, irreverence, cool, and phantasmagoria. I can barely hear that pathetic intrusion sometimes; the Lennon is so loud.

And that, perhaps, is the worst thing about “Imagine”—it’s hollow enough to allow Lennon’s murder to resound with greater force than his life. It is the original, untouched “Ecce Homo” for an audience determined to confuse worth with sentiment, profundity with moral posturing.

3.

Yoko Ono’s “Imagine” (2018):

She’s removed “the pillowy chord progression; that beckoning four note figure...”, flattened it to a dimly modulated synthscape which grows subtly out of its opening, siren-like drone. And the vocal line cutting through this is a jagged fissure. Plaintive and searching. There’s nothing easy about “easy” anymore. Where Lennon’s vocal was strident, almost as if he were merely asking us to be more like him, Ono’s is downright rueful. “It’s easy if you try...” she speak/sings, promising nothing of the sort. The kind of lie a mother might tell a child to keep her quiet while the two of them hide in a closet from an intruder. A lie freighted with a different kind of truth.

This sky is empty—the onliest sky imaginable. In Denis Johnson’s The Name of the World, a grieving protagonist is freed from faith by a sky like this one, where prayers float unheeded until they dissipate in the blue.

Bass tones now. And something more deftly modulated, like an organ, bearing the imprint of human time-keeping—idiosyncratic and soulful. “Hard” is soft here—brittle—it breaks in her mouth. Is she crying? It’s a decent enough question, and I notice more than a couple commenters in the thread beneath the video voicing it, but the one I’m hung up on: Does anyone else hear how punk she sounds landing on the “too” after “no religion”?—a Johnny Lydon-level of insolence grinding that word out like a toe snuffing a cigarette butt on a sidewalk.

I love the way she “ooh-hoo”s. I feel like I’m at a late night karaoke bar watching someone washed in the glow of the prompter—someone who knows the song in her heart better than she does in her throat. How many nights have I spent like that? Understanding for the first time a piece of contemporary country, say, which had meant nothing to me before hearing the way it meant everything to the Iowa woman wringing out its verses after a long shift at a job she hated. Or that ridiculous Proclaimer’s jig that turned an off-duty Pittsburgh cop into the buoyant life-of-the-party for three minutes every Monday night back in the early ‘O-zies. Or the way a plastered friend of mine once sowed an inexplicable amount of chaos into the crowd of a rowdy campus dive here in Corvallis, nearly getting me into a fight with a newly enlisted marine, before plunging headlong into Counting Crows’ “Round Here”—a song I’d utterly detested until that moment—like it was Ophelia’s mad scene. I’ll never hear it the same again.

Ono has taken the linking conjunction out of “Imagine’s” chorus, somehow rendering it fresh—conspiratorial. “I’m not the only one,” she tells me, without a hint of wistfulness, and I feel like I’m being invited to a meeting of an underground resistance movement called the “Dreamers,” the sort of place I’d be taking my life into my hands to go. She searches me out, her eyes nervous. Or maybe just impatient, it’s tough to tell. She looks like something kiln- fired—like her years have only hardened her. ‘Course I’ll go, I think. If not now, when?

Almost in answer, the figure appears—the same four notes, but inchoate, practically the ghost of a piano. I’m uncertain at first if we both hear it, or if it’s just in my head. Or if I’m hearing the inside of hers? As if the moment we’re stuck in is playing a duet with the past. Her voice plays this trick, too. It’s still, unmistakably, the Ono of “I Felt Like Smashing My Face in a Clear Glass Window,” but, at eighty-five, the chimes are rusted, and it’s now as if the two women—young and old—are both present, or as if the song exists in the tension between them, between 1971 and 2018, between that ethereal piano and this chilly, cislunar ambience.

It’s a span, I suddenly realize, which accounts for nearly my entire life, and it’s as empty as the air where those prayers went.

This is what Ono’s song asks me to imagine.

No one has worked harder to preserve the memory of John Lennon than Yoko Ono.

But it’s a very specific memory. A child’s drawing, I used to think. It’s only now that she’s reclaimed her song from him, that I can hear it for what it truly is: her John Lennon. Yoko’s “Imagine” manages to both contain the original and transform it. In the same way, it holds the forty-seven years which separates these recordings while simultaneously flattening that span. Imagine there’s no past, it says, only what we choose to believe in and what we carry forward.

I may hear the original as borrowed sentiments custom-fit to scale a pop chart dominated at the time by soft rock luminaries like Carole King and James Taylor. But Yoko Ono has approached that song as a sacred object, while at the same time radically revising it on her own, very personal terms. This, I realize, may be as close as I will ever get to the sacred, and why an artist’s unique vision, warts and all, is so vital to me. I require a Howard Finster to show me Christian charity, just as I need Gimenez as a lens to view Christ’s face. And while I recognize that unlike these, Yoko Ono is a seasoned and sophisticated artist, I need to stand in Ono’s warbling “world,” in order to appreciate the beauty of “Imagine.”

David Turkel (pictured here in 1971, the year "Imagine" was released), lives in Oregon where he is currently at work on a book debunking the merits of Golden Retrievers.