Patrick thought he got it from a one-night stand after his boyfriend broke up with him. It was hard to imagine anybody breaking up with Patrick, though. He looked like he’d stepped out of a Ralph Lauren ad, all patrician, hardy, and mythically American. Once you got over the shock of his looks, it was his kindness and generosity that set him apart from a magazine model. After I got a job at the coffeehouse where he worked, taking a shift in the cruel hours of the morning, he’d get there even earlier, finish all the opening tasks, and meet me at the door with a cup of tea. We’d sit behind the counter and listen to Kate Bush in the calm light before the morning rush. I soon discovered a sharp wit and withering sarcasm hiding behind his swimming pool eyes.

Patrick was also the first man I knew who had ARC, as they were calling it then. AIDS-Related Complex. As I understood it, ARC was a kind of pre-AIDS, in which somebody could carry markers of the disease without the weight of a full-blown death sentence. Something about saying ARC instead of AIDS also suggested the possibility of reversal, if not recovery. Like having a cold that never turns into the flu.

Once I started working the weekend closing shifts, I didn’t see Patrick as often. He tired easily and cut back his hours. I supposed he had better things to do than sling coffee to the entitled members of the university’s panhellenic associations. One of the jokes going around the fraternities that year was that “gay” stood for “Got AIDS Yet?”

At night the cafe became a gathering place for artists, intellectuals, and other denizens of the leisure class. Every Friday and Saturday after the bars closed, people streamed into the coffeehouse to wind down or to have another slug to keep the party going. A new dance club had just opened and the after-hours revelers made me feel like I was missing out. I did my best to flirt in the way I learned from watching Patrick. Simple questions with a smile and plausible deniability if the potential hookup wasn’t receptive to more. How’s your night going? What are you up to later? Patrick made it look so easy. As it turned out, it was. Occasionally I could take somebody home, if they didn’t mind waiting til 3 after I closed up shop. We were young, after all, and lack of sleep was no impediment to a good time.

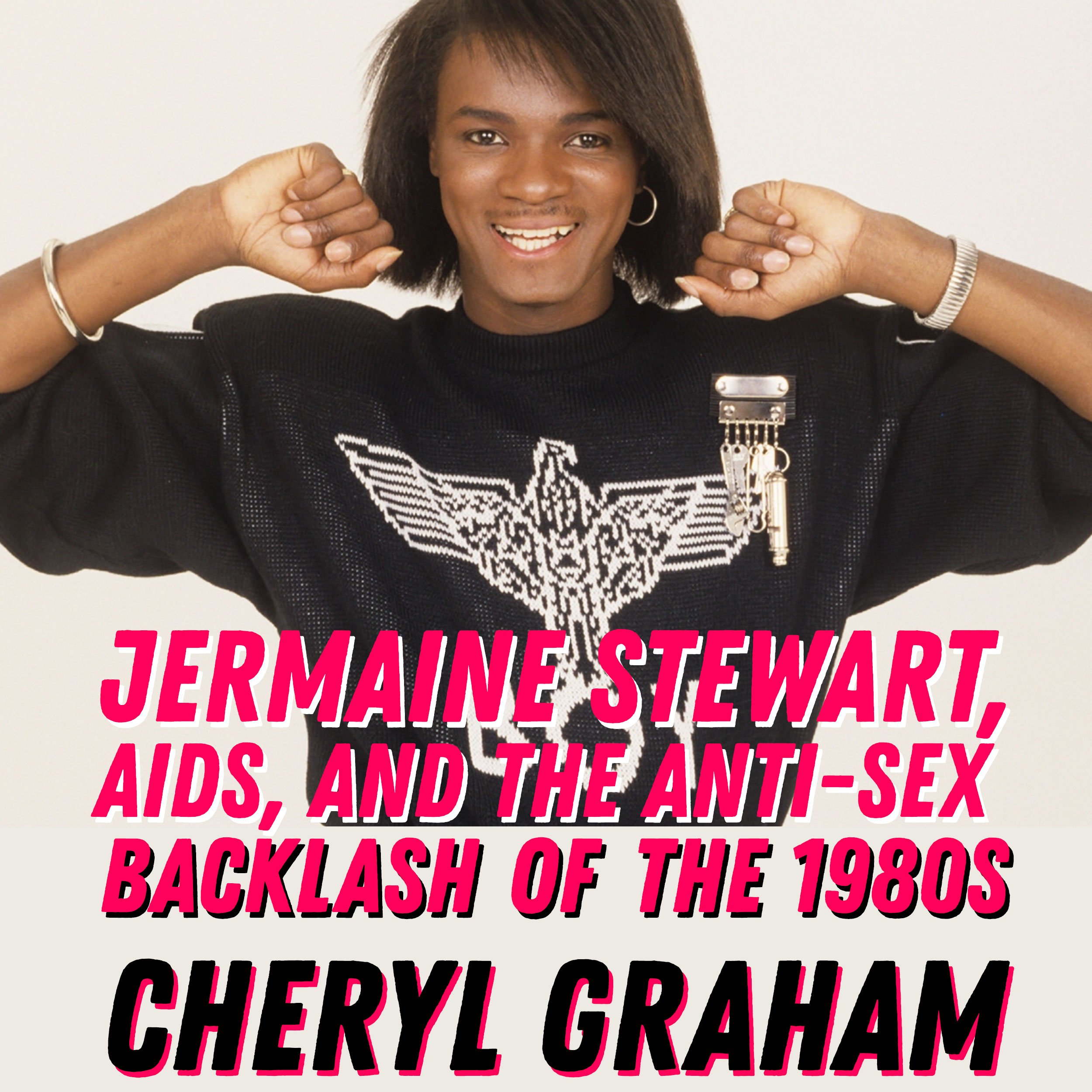

One of the songs I would have danced to that summer, 1986, was Jermaine Stewart’s “We Don’t Have to Take Our Clothes Off,” a floor-filler whose syrupy synth bass, chiming keyboards, punchy horns, and singalong hook made the whole club levitate.

The song’s promotion of abstinence—or at least of pumping the brakes on promiscuity—reflected the growing anti-sex backlash of the 80s. In 1986 the President of the United States had uttered the acronym AIDS in public only once. By that time, nearly 25,000 people were dead in the US and 36,000 were infected with the virus. There were no drugs to treat the disease; it was 100% fatal. Many right-wing pundits and indeed members of the Reagan administration considered AIDS a moral issue rather than a public health one. The President’s Press Secretary made jokes about it, taunting a reporter who simply asked whether Reagan was going to do something. Before he became White House Communications Director, Pat Buchanan wrote a column in which he sneered, “The poor homosexuals — they have declared war upon nature, and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.” North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms wanted to quarantine anyone who tested positive. Conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. proposed tattooing HIV-positive gay men on the buttocks.

No wonder songwriters in the 1980s began turning away from the free love ethos of the 70s toward more conservative themes. Many hits from the time reflect that shift. “Papa Don’t Preach,” in which the young Madonna with child declares she’s keeping her baby, was seen by some on the left as promoting teen pregnancy, while conservatives embraced it as an anti-abortion anthem. George Michael’s provocative “I Want Your Sex” was banned from radio in the UK, and MTV insisted on a video edit in which the singer writes “explore monogamy” on his TV girlfriend’s naked back. Even Prince, that self-described Sexy MF, only wanted “your extra time and your kiss.”

“We Don’t Have to Take Our Clothes Off” begins:

Not a word from your lips

You just took for granted that I want to skinny dip

A quick hit, that's your game

But I'm not a piece of meat, stimulate my brain

Stewart, with his peach-fuzzed upper lip, pressed hair, and effeminate style was hardly a piece of meat. He barely had any meat on him. His voice, while strong, could easily be mistaken for an alto belonging to disco-era divas like Cheryl Lynn or Gwen Guthrie.

Before his breakout song, Stewart grazed the Top 40 with a tune called “The Word Is Out,” about a secret love that’s no longer under wraps. The word might have been out, but Jermaine wasn’t. In the song’s video he plants a chaste kiss on the woman who plays his paramour, then spends the next three minutes dancing in a ballet studio. The dance sequence might have been a clue to Stewart’s sexual orientation, but only to anyone with working eyesight. This is not to say that all male dancers are gay or that leg warmers weren’t all the rage in the 80s, but as one YouTube commenter put it forty years later, “I knew that boy was sweet the first time I laid eyes on him.”

Nevertheless, director David Fincher paired Stewart with a woman for “Clothes Off.” The video doesn’t exactly align with the song’s chorus, we don’t have to take our clothes off to have a good time. It starts with a young seductress already in a state of undress, casting off her gloves, hat, and coat well before the song’s refrain. Stewart himself goes through a supercut of outfit changes over the course of the video, so his clothes had to have come off in between. And he’s obviously having a good time. By the song’s end the woman, down to a bow tie and blazer, paws at Stewart’s shirt buttons while he lip-synchs oh no, no, no as the music fades out.

In a 1988 interview, Stewart reflects on the song, saying, “I think it made a lot of people’s minds open up a little bit. … We wanted to use the song as a theme to say you don't have to do all the negative things that society forces on you. You don't have to drink and drive. You don't have to take drugs early. The girls don't have to get pregnant early. So the clothes bit was to get people's attention, which it did and I'm glad it was a positive message.”

I don’t remember anybody forcing me to drink and drive, or girls getting pregnant of their own accord, nor do I remember the song’s “message” as positive or negative. I just remember it, in today’s parlance, as a banger. Only without the banging.

Just slow down if you want me

A man wants to be approached cool and romantically

Does he though? Not according to the overwhelming majority of songs in the pop canon sung from a male point of view. I appreciate that the track offers a different take, but its buoyant melody seems to be underscored by shame. Shame at simply enjoying what AIDS activist Robert Rafsky called a “human thing.” What if Stewart had really been allowed to live his truth? What if the women in his videos were men? What if instead of derision and hysteria, AIDS was met with compassion and courage?

Patrick moved back east to be with his family. He seemed to be in fine health when he came back to Tucson for a visit several months later. We hennaed our hair one afternoon, sitting in the sun, heads wrapped in plastic bags to set the color. Patrick’s chest was still broad and his skin glowed in the sunlight. His smile still lit up an already brilliant day. When I drank from his beer can by mistake, worry snagged my mind. The concern was fleeting, but the guilt I felt for even entertaining that fear lingered for years.

It couldn’t have been easy to be a gay Black man in the 80s, in or out of the closet. Stewart didn’t possess the cultivated, rough-hewn masculinity that allowed George Michael to pass for straight. He might have loved to make a video filled with debauched leather men, à la Frankie Goes To Hollywood, or one with the fraught but redemptive narrative of “Smalltown Boy” by Bronski Beat. Those two videos were the exception to the rule. They may have paved the way for a more authentic expression in later years, but the men in those bands were privileged and white. Stewart had to use feminine pronouns in his songs and dance with women in his videos to maintain the pretense of heterosexuality.

Despite the need to keep his private life hidden, Stewart’s public image was always happy and gracious. In every interview from that year, he comes across as shy and a little impatient, as though he can’t wait to get back on the floor to dance and sing. The smile on his face seems to say that he can’t believe his good fortune, living his dream as his song climbs the charts. Even as the success of that song and his rising star kept him in the closet.

In 1987 Ronald Reagan finally made a policy speech declaring AIDS to be a high public health priority. On the very same day, he gutted the budget earmarked to study the disease and care for those afflicted with it. 41,000 Americans were dead.

Patrick died the next year, among his family on the east coast. He was 28. I didn’t see him suffer, I only knew the exuberant and gentle soul who loved tea and Kate Bush and life. At his memorial service, one of his friends told a story of the two of them driving on Cape Cod one night. Patrick was near the end at this point, his body diminishing and in pain. He lay back in the passenger seat, looking up at the clear sky through the sunroof. He stayed silent for such a long time that his friend worried she’d lose him there in the car before they got home. She checked several times to make sure he was still breathing. When at last he roused, his eyes fixed on the stars above, he looked over, smiled, and said, “It doesn’t get any better than this.”

A decade later, in 1997, William Jermaine Stewart died of complications due to AIDS, one of 16,516 US AIDS deaths that year. He was 39. Roughly 400,000 Americans had died since the beginning of the epidemic. For the next 17 years, the stylish young singer whose song became a worldwide hit lay in an unmarked grave. A fan placed a stone at the site in 2014.

When I hear “We Don’t Have to Take Our Clothes Off” now, I can conjure those years in the mid-80s, filled, as they were, with frivolous dance songs. It’s a low bar, but We can dance and party all night and drink some cherry wine remains one of the more risible lines from the era. Nevertheless, when Stewart adds uh-huh after the refrain, I hear yearning. The subtle but plaintive break when his voice slides up to that A-flat summons a visceral melancholy, and I can’t help feeling wistful when the na-na-na’s fade out at the end. Living through the ensuing four decades, when some of my friends didn’t, has left me attuned to the sound of lost potential. In 1988, with the rest of his life before him, Stewart said, “I want people to know that I’m here, I’m gonna be here, I’m not a one hit wonder.” In the 1980s, so many young men wanted the same thing.

(L-R) Friends Cheryl Graham, Patrick Grace, and Tim McConville, Tucson, March 1988

Cheryl Graham, like many of her generation, spent the 80’s playing in bands and going to art school. Many (many) years later, she wound up in Iowa City, playing pub trivia and going to writing school. Her essays have appeared in the New York Times, Essay Daily, Barren Magazine, Identity Theory, and others. She writes about music for PopMatters. [TWITTER]