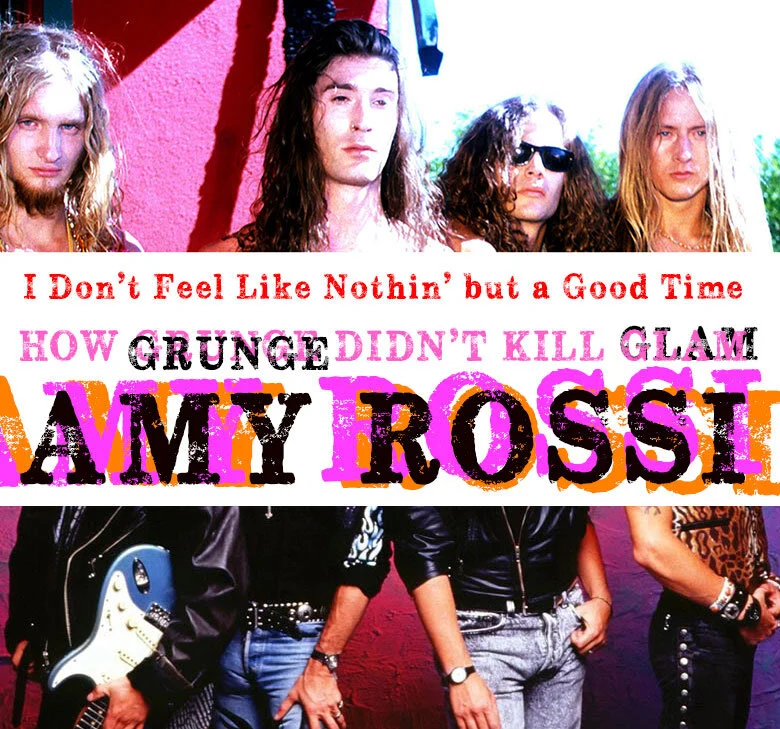

“I Don’t Feel Like Nothing But a Good Time”: How Grunge Didn’t Kill Glam by amy rossi

Most rock docs or essays with a retrospective bent on 1980s glam metal offer the same clean narrative: Quiet Riot’s number one album, the rise of Motley Crue then Poison, the music videos, the copycat bands and Guns N’ Roses blowing onto the scene with something new and raw, “Cherry Pie” as emblematic of everything wrong, and then grunge ending it all.

It’s a tidy story. And it’s not true.

Quiet Riot’s Metal Health reached number one on the Billboard charts in November 1983, the first heavy metal album to do so. Nirvana’s Nevermind, the album credited with ending glam metal’s reign, took the top spot in January 1992.

In between? A pretty solid run, aided immensely—and then cut down—by MTV.

Ever since white people stole rock music, television has helped make rock stars, selling an image and experience, packaging cool. Variety shows like Ed Sullivan’s helped create a rock n’ roll image long before MTV was an idea. What MTV did was make music constantly, pervasively visual. And glam metal bands who cut their teeth trying to stand out by any possible measure—confetti cannons, strippers on stage, silly string, searing neon flyers—in a 1.5-mile stretch of the Sunset Strip, where you could choose between seeing a show at the Roxy, the Whisky, or Gazzari’s, were ready to be pervasively visual.

Just not forever.

There’s a binary created by the grunge-killing-glam narrative, a kind of musical purity test. Glam metal was oversaturated with copycat bands pushing a tired formula of anthems and power ballads; grunge bands were doing something new and different, speaking to the time. Nevermind that the versions of the same argument followed grunge-era bands as well. One was artifice. The other was real.

Alice in Chains as Diamond Lie, in full 1988 style, covering “Suffragette City.”

The basic facts are true enough, to a point, but somehow it ends up implicating only the glam metal bands and not the executives who were trying to cash in—the ones who were actually pushing the formula, paying for hair extensions, repackaging bands who had failed to attract an audience before, signing new groups because they were similar enough to a successful act rather than looking for something different.

It’s not insignificant that “Cherry Pie” is the song and video that’s used as a stand-in for the tired excess of glam metal. Jani Lane had planned for the album’s title track to be “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” a song he was truly proud of. The president of his record label wanted something else, something catchier. Lane cranked out “Cherry Pie,” and apparently the pizza box on which he scrawled the lyrics in less than an hour could at one point be viewed at a Hard Rock Cafe in Florida.

In the book I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution, Adam Levine of Maroon 5 announces that “even at 12 years old, I thought, ‘wow, how tacky,” when he first saw the video for “Cherry Pie.” Of Montreal’s Kevin Barnes writes in Pitchfork that being a hair metal fan as a teen is a “skeleton in his closet,” and even if it’s tongue-in-cheek, we’re supposed to get what he means—the confession is inherently embarrassing.

It’s the purity test in action: the line of thinking assumes glam metal as lesser. Even a kid could find it tacky (or an adult could claim that they found it tacky at the time). It’s just a production. It’s inauthentic—all style, no substance.

But a lot of art is authentic before money gets involved.

It happened with glam metal, and it happened after Nirvana hit number 1. Steve Knopper calls it the Grunge Gold Rush: every label was looking for their Nirvana—just like every label had looked for their Poison, Guns N’ Roses, or Motley Crue a few years before. The genre that was supposed to save us from videos and bands that looked and sounded the same was quickly going to be packaged and replicated and commercialized by record labels who were prepared to treat another scene as a monolith in order to cash in.

In the 1996 documentary Hype!, about the early-90s rise of what outsiders would call the Seattle scene, Megan Jasper of Sub Pop Records described the frenzy as “quarter until six on Christmas Eve at a shopping mall when the mall closes at 6 o’clock, when it’s too crazy and it’s loaded with sub-moronic idiots prancing around buying anything they can their hands on.” And Nirvana’s former publicist Susie Tennant recalls bands who’d never played live receiving huge advances.

By 1995, Spokane’s Spokesman-Review was lamenting the second wave of copycat grunge bands, placing Stone Temple Pilots firmly in the first wave. STP were the poseurs, cogs in the corporate machine and fodder for Beavis and Butthead, for no reason that seems to hold almost 30 years later. Sure, early singles may have included Scott Weiland making use of Eddie Vedder’s rigid-jawed yarl, but the band’s only real transgression was having the misfortune of releasing an album after Soundgarden, Nirvana, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam did. Swap out a few adjectives and band names, and you could probably find something similar in LA Weekly 10 years before.

“It’s so profitable, and they’ll keep taking and taking and they can’t restrain themselves,” Vedder said in Hype!

This is 100% accurate, and also Pearl Jam themselves signed to a major label, as did Nirvana.

To be clear, I’m not questioning the authenticity of either of these bands.. You can participate in the commercial music industry and also push it to be better. The more interesting thing to me is how it opens up questions about accepted definitions for the visual signifiers of authenticity versus artifice, as videos made image important for the consumption of each genre.

While watching both Hype! and a 1997 MTV program called “It Came from the Eighties,” I was struck by Selene Vigil of 7 Year Bitch and Tom Keifer of Cinderella having the same dispirited response, almost word-for-word, to reading their reviews: all anyone wrote about was what they looked like, not about the music. Even the name of each genre is based on image—both grunge and glam (or hair metal) became shorthands for appearance as much as, if not more than, sound.

So why is the image projected by Pearl Jam viewed as more authentic than that of Poison? After all, there are some pretty impressive coifs in early Pearl Jam videos. Both images are consumed and commodified; both are styles that are intended to define the person embodying them. A stripped-down anti-style, even one based on weather, is still a style. It’s entirely possible to feel like your most authentic self in leather and eyeliner, regardless of your gender. It doesn’t feel like a coincidence that the bands brushed off as shallow are the ones who appropriated traditionally feminine—read: obvious—styles.

For me, the narrative of grunge killing glam persists because in its neatness, it gives hair metal a comeuppance that hindsight has suggested is necessary. It was too excessive, too decadent, too much—something had to give. The unspoken part of “grunge killed glam metal” is that the latter deserved it.

Photo from metalsucks.net.

One of the problems with the narrative is that it assumes glam metal intended to stay static and that grunge ignored an entire decade of popular music. It avoids the overlapping period of commercial success—at the end of 1991, both Nirvana and Firehouse were occupying the upper quadrant of the Billboard Top 200. It skips over the fact that Alice in Chains opened up for Van Halen and Poison in 1991, the latter at Bret Michaels’ request, as he tells it, right in the Pacific Northwest. (The openers were even invited back on stage to join the headliners for a cover of “Rock and Roll Nite.”) It ignores the fact that Alice in Chains first played as both Diamond Lie and Alice N’ Chains as a glam metal band in their own right. It overlooks glam rock’s clear influence on Stone Temple Pilots, the elements of the genre that were in full force on 1997’s Tiny Music... and in the band Scott Weiland would later form with members of the Cult and Guns N’ Roses.

And, despite the visual evidence, it ignores the very simple fact that fashion and style were changing by the late 80s, and plenty of glam bands changed along with it.

You can only push excess so far before it loses its thrill, its originality. Cinderella is remembered for how they appeared in the “Nobody’s Fool” video but the lace and corset tops were gone with the second album. By the time we get to the “Don’t Go Away Mad” video, Tommy Lee and Nikki Sixx have traded big hair and platforms for undercuts and Docs. Once Poison caught everyone’s eye with their heavy makeup for the Look What the Cat Dragged In cover, they toned it down significantly, embracing a more biker aesthetic, and Bon Jovi wasn’t too glam for Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready to basically crib Richie Sambora’s entire look in Pearl Jam’s “Alive” video.

Not Richie Sambora.

Or take the much-maligned Trixter, a New Jersey band that gets casually thrown into conversation as synonymous with an oversaturated, copycat glam metal market. But if you watch the video for “Give It to Me Good,” it’s just as much jeans and flannel as it is hair, almost like it’s two different bands. The action takes place primarily in a garage and in a park—no fireworks or spandex or glitz. There’s even a young woman wearing umbros. Maybe Trixter was a copycat band, but looking at them in 1989, straddling the aesthetic of the past and the future, they don’t appear to be too concerned about copying style.

Which is to say they didn’t look all that different than Alice in Chains did around the time “We Die Young” was released.

These signifiers persist in telling us who to take seriously and who to brush off. Grunge looks more unaffected, more accessible, and that makes it easier to take songs with a serious message seriously. The big hair glam look appears to nullify what’s in the music; power ballads are dismissed as chick bait (as though that’s automatically a negative) without any acknowledgment for how hard both Poison and Skid Row went in “Something to Believe In” and “18 and Life,” respectively. Jon Bon Jovi has said trickle-down economics policies influenced Tommy and Gina’s story in “Livin’ on a Prayer,” and if that sounds like a joke, well, sometimes the least threatening person carries the message best. Warrant’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is, at its heart, a song about corrupt law enforcement, and the video is truly weird in its attempt to do something different.

But that’s not the video that lasted. And one of the ways the narrative persists is through the very same means glam metal gained and lost commercial success. In the aforementioned “It Came from the Eighties” episode, glam metal artists are basically invited by MTV to distance themselves from the era.

There’s a deep pathos to Jani Lane saying, “Alright, it’s our fault. We were the band who brought down the 80s,” knowing how his story ends. Bret Michaels tries to answer a question about the demise of glam metal, a question that again ignores the fact that he’d enjoyed playing with one of the bands credited with bringing about his own group’s end. He rambles on about how in every genre of music there are the A-list performers who raise the bar and then the B and the C, before finally getting exasperated and saying, “I don’t know what the fuck I’m saying. I don’t know. MTV stopped playing the videos.” Like Jani Lane, he’s laughing, but there’s a genuine pain in that moment.

And the fact that this aired on MTV, without the MTV interviewer’s response, shows how the narrative took root—even though Variety had the answer by November 1992. Both columnist Lonn Friend and marketing executive Bob Chiappardi pointed to MTV’s abrupt pivot to grunge videos, not the existence of grunge itself. “The big thing that’s killing it, though, is MTV, because they’ve basically turned their backs on a lot of these bands. I don’t know if it’s fair or not because they made it the monster that it was,” Chiappardi said.

It continues now: a recent A&E special about the early years of MTV recounts how its staff became tastemakers—for a certain kind of music, anyhow. Executives look back on their decision to exclude Rick James and cite the sexual content of the “Super Freak” video, noting that it didn’t get past the approval board. Gale Sparrow, who was part of talent relations, makes her disgust clear: “That video should have been shown in a strip club. He was a pimp with a bunch of women.”

No one has much better things to say about the hair metal videos—distilling them all into basically the worst parts of “Looks That Kill” (1983) and “Cherry Pie” (1990) despite the time gap that exists between the two. Whatever made Rick James inappropriate in 1981 didn’t seem to apply any longer.

Misogyny is often cited as a reason hair metal needed to die. And grunge undoubtedly took rock music in a much stronger direction there, with more women artists receiving attention, men artists taking vocal feminist stances, and songs and videos that weren’t seeking sex.

But from this vantage point, it looks like the people programming the videos are comfortable dismissing glam now without taking any culpability. It’s one thing to evolve your position, like some metal artists who’ve taken to using their platform for social issues. It’s another to act like these videos spanning nearly a decade came out of a vacuum and that MTV had no role in creating and promoting this as a sellable image for others to replicate and no role in dumping it.

“I just held my breath and thought, ‘This has to be over soon.’ It was demoralizing,” says Judy McGrath of the glam metal video era in the A&E special. McGrath rose from MTV promo writer to eventual CEO, and her concerns are reiterated in I Want My MTV—and brushed off by a male colleague as an “internal controversy.”

Glam metal’s misogyny is worthy of critique. It’s curious when people only seem to invoke misogyny when it relates to something they don’t like, but not when, say, it comes to ignoring concerns voiced by a colleague like McGrath.

And think about the language employed to talk about glam as opposed to grunge: in 2009, Chuck Eddy referred to certain musicians as “glam poodles” in SPIN magazine; Kevin Barnes did the same while also describing Ratt’s look as the “gayest biker gang ever.” Music critic Dawn Anderson puts the bands who came from Seattle in context against “this big poodle metal scene, just tons and tons of hairspray, eyeliner…”

In 1990, Jani Lane talked about Warrant being stereotyped as a young girl’s band, and Susan Orlean’s profile of Bon Jovi explains how the release of “Wanted, Dead or Alive” as a single was rushed because the band was drawing too many female fans and needed to delay the next ballad. Not only did the feminized image hurt glam’s credibility, so did the legions of women who found the genre more accessible.

It becomes an ouroboros of sorts. In perpetuating the idea that glam needed to die, it becomes all too easy to slip into speech that degrades or dismisses women: the very thing glam is (fairly) critiqued for.

Of course, in all the commodified nostalgia VH1 and MTV spent the early parts of the 2000s peddling, artists aren’t asked about sexism in lyrics or videos—or even about their decision to appropriate style. Those angles aren't really pushed. It’s kept as surface-level as the bands are accused of being, limited to the rise and fall and advent of grunge without much context for the world the music was created in.

Distinct time periods launched glam and grunge, the things that inform the kind of music people want to make and hear: coming out of a recession and entering one, the beginning of the Reagan era and the repercussions of it, AIDS as ignored and misunderstood and AIDS as a part of public health. It makes sense that rock fans needed something more or at least different—the world itself was both more and different.

Instead of it being another moment when music evolved in response to its surroundings, this time, audiences were saturated with 24-hours’ worth of visual markers of that change.

Grunge didn’t give Tom Keifer vocal cord paralysis. Grunge didn’t create conflict between George Lynch and Don Dokken. Grunge wasn’t responsible for the addictions that fractured bands like Guns N’ Roses, Motley Crue, Ratt, and Poison. And grunge didn’t program the video schedule.

The music you want to make when you’re 22 isn’t necessarily the music you want to make at 28. And the music you make when you’re wanting is different from the music you make when you’re having, which is likely where the real authenticity versus artifice argument lies. What Kurt Cobain said of the grunge label applies across the board: “You have to take a chance and hope that either a totally different audience accepts you or the same audience grows with you.”

Every era has its expiration date, for whatever reason. We should continue pressing the issue of misogyny in glam metal because being honest about music’s past helps build a more equitable path forward—as we should press the predation and abuses of the so-called “baby groupie” era in the early 70s and the culture that gives credence to speculation that Courtney Love had anything to do with her husband’s death (and that persists in defining her artistry in relation to his). And, while the stakes are not the same, it’s also reasonable to question why big fun songs that attract a lot of women and bands who adopt an over-the-top feminine style are dismissed as lacking substance. Big fun isn’t the most important thing, but it’s part of rock.

To position glam metal as having failed or grunge as a killer because one didn’t last forever and the other happened to be next is to ignore everything that came before and everything that came after. The conclusion grunge met looked different, and was more tragic, but it came all the same.

In the end, grunge couldn’t have killed “the hair bands” because neither of those things exist. Those particular labels were useful primarily for record companies, for scouts, for the people who choose which videos to play or to stop playing. It’s marketing, and if anything helped MTV end the glam metal era, it was the choice to try to make bands fit in a box of what had been successful before rather than play to individual strengths, the choice to create a formula rather than highlight what made a band popular in the club scene, the choice to focus on a quick buck now and developing talent later. While glam metal bands indulged in excess, so did the corporate machine.

And instead of learning from these missteps, when Nevermind hit #1, it was time to do it all again.

Amy Rossi might be the only person who went from grunge to glam metal instead of the other way around. She writes fiction and essays, mostly about music, and is currently at work on a second novel. She thinks a lot about Guns N’ Roses’ live cover of Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun.” Find out more at amyrossi.com.