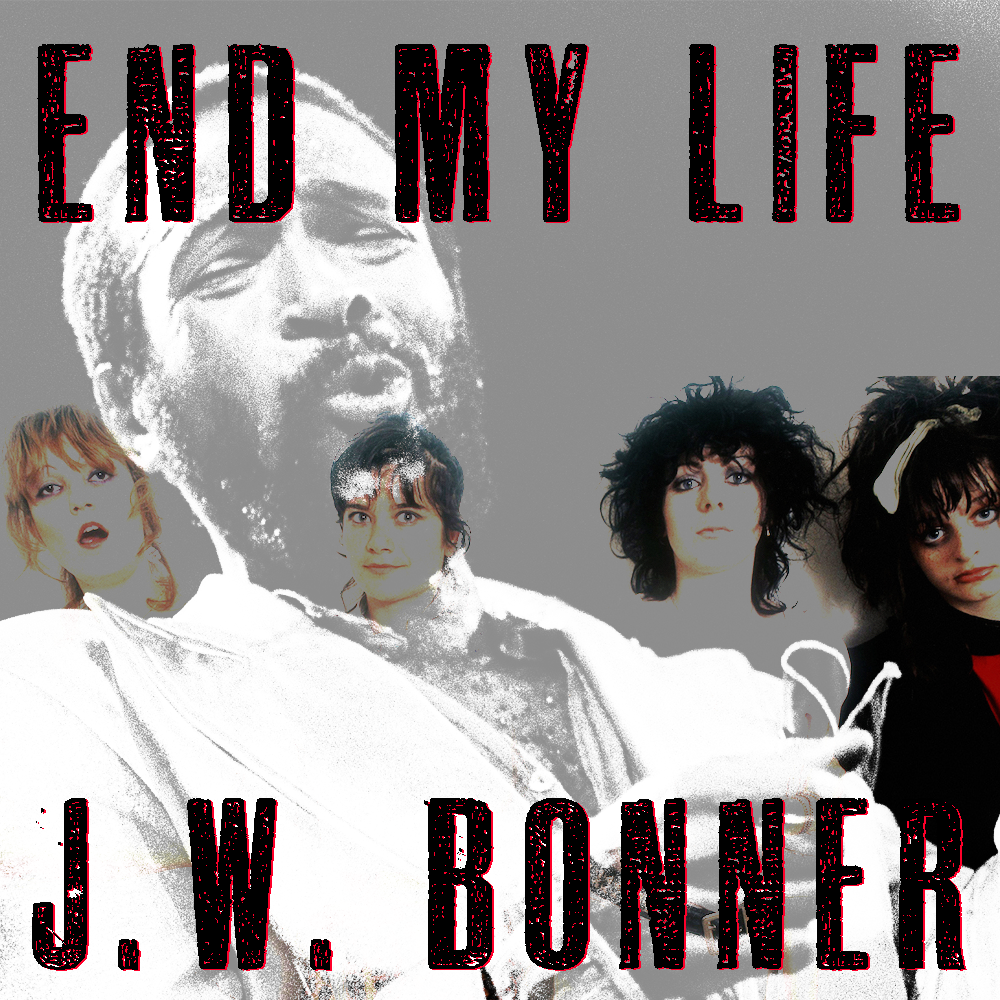

end my life: marvin gaye and the slits’ versions of “i heard it through the grapevine” by j. w. bonner

There is no history without nuance.

—Norman Mailer, Miami and the Siege of Chicago

[A] critic’s job is not only to define the context of an artist’s work but to expand that context.

—Greil Marcus, Mystery Train

Natty [Bumppo]is a saint with a gun….[H]e kills…only to live.

—D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature

Prelude: He Kills Only To Live

Durham, North Carolina 1968

We were headed home from a regular school day at Lakeview Elementary. My mother drove our VW bus, the same vehicle that was pushed wildly from side to side whenever we ventured on the road in high winds, creating quick, gut-wrenching moments not unlike a plane in turbulence. I sat on the passenger side, in the front with my mother; my two sisters claimed seats behind us. Our daily drive, from school to our rancher-leased Cornwallis Road home on fifteen acres in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, routed us through a housing project. On this early April afternoon, warm enough to roll the windows down, we encountered stopped traffic. In the distance, the lights of police cars. I thought of possible reasons for this delay: driver license check, an accident.

Then, I saw her headed toward us. She was moving quickly between the opposing lines of cars, threading her way in a jerky hurry down the two-lane center line. She wore a light trench coat, opened, flapping. One arm appeared to clutch a bag or sack of some sort to her ribs; the other arm was tight to her side, the hand fisted by her throat, an image of grief or worry. She might have been fleeing a demon, personal disaster. Her spastic way of moving, hampered by coat and emotion, suggested bereavement, sorrow.

Policemen: they, too, moved toward our car. The woman scurried closer. My mother, without comment, began to roll up her window. As the woman drew alongside our VW bus, her hand, the one that had been positioned by her throat, struck out. There was a clack of something sharp hitting glass, a glint off a blade. The woman continued past us, policemen closing.

I don’t know why I closed the window, my mother said. She trembled. We stare more wide-eyed and intent on the world around us, hoping to lose nothing of the legal pursuit of this woman assailant.

That night I listened to the radio’s grapevine reports: martial law declared by the mayor; downtown Durham had burned. Dr. Martin Luther King, the man whose voice had entered my ears with a deepness and authority of the most ancient and venerated of my family tribe, had been murdered, assassinated. That woman had tried to claim vengeance, pay back: my mother’s white life. Toni Morrison’s Seven Days members, from her novel Song of Solomon, would not appear in print for almost another decade, but that woman—frustrated, enraged, unhinged—had wanted some reclamation, some maintenance of a ratio, though my mother, whom I love, would not have come close to serving as an equal sacrifice for the man, the year, and the decade.

The Sixties: All of It

Marvin Gaye’s first number one hit, “I Heard it Through the Grapevine,” was a song written in 1966, and it became a hit for him at the end of 1968. (It’s a song that was recorded by other artists before Gaye’s recording of the song, so it’s already a bit of a cover of covers, and Motown released a version by Gladys Knight, just after the Summer of Love, in September ’67, a year before Gaye’s version was authorized for public release.) The song focuses on a relationship that is a lie; he hears through the grapevine that his love is back with an earlier lover. She has been unfaithful in her promise of love to him. As the country came to the end of ’68 and entered the first weeks of 1969, that sense of betrayal may have been palpable outside the AM radio dial: the promise of love in ’67 reduced to the loss of Dr. King and Bobby Kennedy in 1968. Those dreams, of racial and economic equality, of a possible reclamation of the myth of Camelot (never mind its messy reality, though the myth-mongerers, too, were providing a reading of the Arthurian myth that conveniently left out the political and sexual intrigue that the Kennedy administration rhymed), were finished, dead.

In the final essay, titled “Goodbye to All That,” from her 1968 collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joan Didion describes her post college graduation New York City years, moving into a four room apartment and leaving it almost entirely empty except for “[hanging] fifty yards of yellow theatrical silk across the bedroom windows, because I had some idea that the gold light would make me feel better, but I did not bother to weigh the curtains correctly and all that summer the long panels of transparent golden silk would blow out the windows and get tangled and drenched in the afternoon thunderstorms.” Those golden dreams of equality and freedom were proving as messily tangled, those golden moral decisions as difficult to weigh, as these improvised curtains. The decade’s improvisations ended, as did Didion’s New York experience, with the “[discovery] that not all of the promises would be kept, that some things are in fact irrevocable and that it had counted after all, every evasion and procrastination, every mistake, every word, all of it.” The whispers of those evasions and losses and their consequences filtered through the grapevine of politics and culture: love and loss conjoined in one country, in one year. Gaye turns that anger and violence of the American landscape at decade’s end and makes them soar in song.

The Grave’s a Fine and Private Place

Four weeks after charting, Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” entered the number one position on December 14, 1968, bumping the Supremes and “Love Child” to number two. Gaye has turned from the sweet, summery Motown sound on which he’d built his reputation (the Temptations follow this shift as well) and jumped into murkier musical waters. Norman Whitfield, co-writer and producer of the single, one of the greatest producers during this time period in American pop music, has created a driving song of psychedelic-tinged soul music. At the same time, “Grapevine” creates a claustrophobic and unsettled sound and tone. The song is the sound of suspicion—about a lover, about authority, about love, about truth—bitterly confirmed.

Clearly the song is about infidelity. The Gladys Knight version, which made it to number two exactly a year earlier, is a classic tale of a righteous woman scorned by her man. She overhears the whispered tales of his philandering in the church pews on Sunday and in the supermarket during the working week. She doesn’t really want to know: she has kids at home, bills to pay, and a no-good, sonofabitch sharing her bed at night—when he makes it home. She’s innocent and heartbroken. She’s the conventional stock victim of soul and country music, but with the added fire that comes when you’re competing with Aretha Franklin for rave-ups and record sales.

Gaye’s version predates Knight’s. But, according to Fred Bronson’s The Billboard Book of Number 1 Hits, Gaye’s was not the first. Motown’s Smoky Robinson and the Miracles and the Isley Brothers recorded earlier versions. Barry Gordy, Motown founder and brother-in-law of Gaye, nixed the Gaye version when it was recorded in 1967. Maybe Gordy thought Gaye’s version was too dark to be marketable; 1967 Motown was dominated by the Four Tops and The Supremes, who just wanted their listeners to know how sweet it was to be loved.

By the time Gordy permitted the release of Gaye’s version of the song, America looked different. Detroit had burned shortly after Gaye’s recording. The deaths of MLK and Bobby Kennedy had led to fires and then to the raucous Chicago Convention. As Mailer documents in Miami and the Siege of Chicago, March through June of ’68 changed the political landscape: on March 31, LBJ announces to the nation, at the very end of a national address on the country’s Vietnam policy, in a single sentence (“I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”) at the beginning of the next to last paragraph in a speech of more than thirty paragraphs, that he will not seek the Democratic nomination (a Gallup poll of that time period indicated only 23% approve of the Johnson Administration’s handling of Vietnam); on April 2, McCarthy wins the Wisconsin primary; on April 4, Dr. King is assassinated; on April 23, Columbia University students barricade the Dean’s office (they are finally removed in a police raid that leaves 150 people hurt; a 1968 Time article on “today’s undergraduate rebels” opined that “none [of the student] requests are at all absurd”); on May 10, France experiences the Sorbonne student/worker uprising; on June 3, Andy Warhol is shot; on June 4, Bobby Kennedy barely wins the California primary (45% to McCarthy’s 42%: Humphrey wins a mere 12%) and is shot that evening, dying the next day. In August, Humphrey pulls out a tainted Democratic nomination; for example, as Mailer notes, Pennsylvania gave 90% of its primary vote to McCarthy but Humphrey wins the delegates at the convention, an accomplishment that Trump would certainly admire—if he were to read history.

In a significant event after Mailer’s coverage of the conventions but, again, a full month prior to Gaye’s single charting, the 1968 student protests in Mexico City lead to the massacre on October 2 of 200 to 2,000 people, a number that today is indeterminate, because of government fictions that posed as official history. (As reported on a December 1, 2008 NPR All Things Considered broadcast, a story produced by Joe Richman and Anayansi Diaz-Cortes of Radio Diaries, the truth: government agents were positioned to instigate the massacre; they fired on the troops, who, thinking the students had opened fire, responded with a barrage of gunfire—a prelude to Kent State and Jackson State, as if Nixon studied this event as a point of emulation. Ironically, based on the most recent analysis, the first person to fall in the massacre was the general leading the Mexican troops to the plaza, killed by the government he was attempting to serve. One can imagine the former Fox television series 24 having a field day with this kind of plot. Or maybe there’s a way to redo The Manchurian Candidate, though one has to wonder, given the more one learns about government cover-ups, if the premise of the film isn’t profoundly based on truth.) The Mexico City student massacre is a typical case of life imitating art: García Márquez writes in his magnificent novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, published in 1967, of a banana worker massacre of thousands of protestors that is never officially recognized by the government, so that the truth of the event becomes questionable. The Mexican PRI party apparently read the novel as a means or blueprint by which totalitarian governments might rid themselves of pesky troublemakers. (Perhaps the party officials missed the tragic and ironic point of the novel.)

In November 1968, Nixon, who in 1962 had promised the press they wouldn’t have Nixon to kick around any more, has defeated Hubert H. Humphrey, nicknamed the Hump in Mailer’s Miami and the Siege of Chicago, by a half million votes. George Wallace, running as a third party candidate, whose platform appeals to blue collar workers and whose politics appeal to white supremacists and racists, wins 46 electoral votes and almost thirteen percent of the popular vote. Who knows what messages are going through the country’s grapevine.

The “Grapevine” cuckold in Gaye’s version is a bit of a slippery character. If Gladys Knight is testifying to her husband in front of the congregation on Sunday morning, then Gaye is alone in a dark kitchen on a hot summer night when his woman walks through the back door stinking of another man’s sex. Gaye is vindicated. He’s heard the gossip, and now he knows the truth. And it’s really good drama. The cuckold in the shadows is ready to strike. He begins the showdown: “I bet you’re wondering how I knew.”

Gaye’s “Grapevine” opens with a percussive sound: one might imagine the loading mechanism of a carbine or the emphatic slam of keys on the kitchen table—time for our talk, honey. Then the shuffling, creeping organ lays down its track. Percussion, drums and tambourine, bubbles from the song’s bottom. These instruments create a sound almost tribal, almost as if the song were sending a message via the beat established, percussion coding the message to the neighborhood and town’s gossips: he’s starting. Horns and strings sweep in to announce Gaye’s vocal. Whitfield has pitched the arrangement just over Gaye’s usual register to draw out a rawer timber.

“Grapevine” is a subtle number. There’s anger, down by the river anger, beneath the surface. It’s not just about the accusation. When Gaye sings, “losin’ you would end my life, you see,” it sounds like an ultimatum. In the chorus he sings, “I’m just about to lose my mind,” an ominous bit of self-awareness and pleading, laying the ground for all the blues songs of lovers left dead. (As Clutter family killer Perry Smith says in Capote’s mid 60’s classic In Cold Blood, “’It’s easy to kill—a lot easier than passing a bad check.’” This line might justify the lynchings paid to Blacks rather than any payment on the check or promissory note promised by the Declaration or by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, as noted in Dr. King’s classic August 1963 March on Washington Address. Speaking to thousands upon thousands on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, at what would prove in the decades to follow a political Woodstock, King invokes both the writers of the Declaration and Lincoln, the thickest walls of equality in our country he may reference for support, and states to those swelling on the mall before him that

we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the…Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.…America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.…we have come to cash this check—a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.)

You’re not exactly sure what happens in that scene following the last note in Gaye’s song, a fade that has him reminding her he has heard this whole event “through the grapevine.” Has her emotional account with “Grapevine’s” accuser proved insufficiently funded? The tension is not unlike that of the narrator in Poe’s “The Raven,” this sexual news as unbidden as the symbolic bird that may or may not correspond or respond to the poem’s narrator. Perhaps the female backup singers represent the women ready to care for him if he dumps his woman (figuratively in a break up or literally down the river bank), hoping for a bit of this true love, their voices the gossip chain that has led him to this news.

The song tells of three losses: love, mind, life—an order that echoes the savage madness of Vietnam’s worst atrocities. Think of Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried,” both story and collection or novel, in which Lt. Cross loses a man from his unit, partly, Cross thinks, as a result of his obsessive focus on the letters and photograph of a girl from college, mementos which, in disgust with his perceived weakness, Lt. Cross burns in a renewed resolve to become more of a military man and less of a human being. Cross now bears one: his perceived failure a moral, mental, and psychic wound. The stories or chapters of O’Brien’s book are the scars to show the (disbelieving) reader.

Gaye’s version of “Grapevine” is superb: every beat advances the plot, every note lends another dimension to its starring character. This song is Motown’s version of Othello. No other version captures the implicit menace of the song as performed by Gaye/Whitfield, the tone and attitude that were to define the final year of the decade, all the way to Altamont. The only other covers of the song with a special place in my heart include CCR’s eleven-minute epic, from the 1970 album Cosmo’s Factory, and the version by the Slits, recorded just over ten years after Gaye’s hit (an equally turbulent decade coming to its end just as Thatcher’s political rise is complete after over a year of British economic and social unrest), in which the song opens with a head wagging sense of public shame, a honey hummed sound of bees, fingers pointed at a naughty somebody, before the dub beat kicks in, Ari Up’s warbled vocal a strangled imitation of Gaye’s own vocal reach.

There could not be two more distinctive covers. CCR’s is an epic guitar jam, one that Neil Young might have attempted if John Fogerty hadn’t conceived it first. Guitar and percussion intertwine during the chorus and verses, the sound of chopping wood in a bayou byway. Fogerty’s unmistakable voice drawls and trembles, burdened by this news he must now share. When Fogerty finally leaves the words, his guitar gives vent to the anger that the voice has attempted to modulate. No holding back the minutes of the solo: once, a few more words, then, round two, a guitar that spits more vehemently than before, Fogerty strangling the neck of his guitar the way the narrator may be tempted to do to his woman, guitar noise masking mayhem in that little kitchen, coffee dribbling off the table and sugar scattered on the floor, a bourbon glass no longer able to hold whiskey, all words said, the final scratch of guitar notes someone’s nails dragging on wood to push from the floor and attempt some level of dignity.

But as covers go, what the Slits do in transforming Gaye’s “Grapevine” into their own mini, four-minute, reggae-infused, Euripidean tragedy is almost unprecedented. (Writer Reynolds Price used to tell his writing students that if dealing with autobiographical elements, allow them to marinate at least ten years before trying to use in fiction. Maybe the same is true of taking on a cover.) It’s the first recording session for the band since drummer Palmolive’s departure, and she’s been replaced for this song’s recording, as Slits guitarist Viv Albertine notes in her absorbing memoir Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys., by a proper reggae drummer, Maxie “Feelgood” Edwards, who has played with, among others, Dennis Brown and Big Youth. What this band accomplishes with their reimagined Motown sound is a far cry, in only two years, from one of their first recordings, 1977’s demo of “A Boring Life” (as heard on Rough Trade’s 1993 Lipstick Traces), which is all pleasure principle abandonment, giggles and verbal strutting, followed by an assault of guitar, bellows and shouts, screeches and squawks. There’s such profound glee in this musical mayhem--it’s rock n roll romper room; these kids are gonna be all right. No boring life for these gals; they’ve turned the rules topsy turvy. It’s a sonic boom, clearing the anarchic ground as much as anything the Sex Pistols manufactured.

And here they now are playing Motown and making it new. The Slits’ “Grapevine” opens with a hum and a percussive clacking that seems from a well, background music to some foregrounded scene buried deep in the mix. (It’s clear that Steve Albini and PJ Harvey learned a thing or two from this cut, the faint vocals and guitars suddenly cyclonic and overwhelming speakers.) Then comes the drum and the sound’s all foreground, whatever scene played out in silence about to take a turn more dramatic. Jagged guitar bursts scratch as if at eyes, a neck, and then Ari Up tries to spit out, stuttering with repressed rage, what she’s here to say: “I bet, I bet, I bet, I bet you wonder how I knew”—and here it comes, voice rising in frustrated anger, trying to say what she needs to say, the truth her lover won’t want to hear, that she can’t believe she has to say, and, if we’re taking bets, mine are on Ari. There are moments when the words get caught in her throat; she can’t get them out: “your plans to make me blue / With some other guy you knew before.” Guy swings into upper register, a strangled sound (as a listener, can’t quite catch her enunciation), upset she has to even say this word in this context.

The vengeance continues to play out in rage with little sense in her voice of sorrow, merely of her betrayal. She sounds as if she inverts the standard lyrics, “I know a man ain't supposed to cry / But these tears I can't hold inside” to equate her anger with a man’s: “these tears I can hold inside” is what I hear—or want to hear.

Midway through the song, metallic percussion carrying the song, a voice starts to count off: “one,” and a pause, “two,” and a pause, then “now” with a rise, almost the mewling of a cat—as when a parental demand has been made and the countdown’s begun before all punishing hell is about to break loose. And the song transitions into a dub beat, song title chorus in repeat, Ari Up’s voice rising with each repetition, a kind of scat replacing the lyrics, the band making sounds (“’Dah dah dah dah!’”) to fill in for the Motown horns (“because,” as Viv Albertine explains in her memoir, “we can’t afford horns”—the true can do spirit of punk), time running out on this lover.

Indeed, time’s running out, not even a minute of this drama left to play. And the song closes with the repetition, four times (a structural mirror to the vocal opening), of “I’m just about to lose my mind,” with the music suddenly cut as her voice lowers on the fourth statement: her voice now menace and calibration. What’s in her hand as the music stops and she says her final words? I’d be stepping back and looking for what might protect me (rolling up a window) from this person possessed (by this music, by this emotion), endowed with something more than mere mortal feeling. She’s been visited by Dionysius—and the question is what’s about to be visited on this person in front of her. There may be blood on the floor and blood on her teeth soon.

It’s not easy to separate “Grapevine’s” betrayal and anger and violence from any cover version—or from the events of Gaye’s own life. He won one Grammy in his lifetime, for one of his best singles, “Sexual Healing,” in the early Eighties. I purchased the 45, perhaps the last single I ever bought, and played the song throughout the spring of ’83, adrift in grad school desire for substantive women, so as to hold in fleshy reality someone my fictions of the time were only attempting to imagine. The song was more than metaphor in my mind. I believed in the Church of Marvin, and I wanted these Words made Flesh. Within a year, Gaye was dead, shot in the chest during an argument with his father in his parents’ home, killed the day before his 45th birthday.

Within a week of “Grapevine” assuming the number one position in the charts, the Apollo 8 spacecraft carries human beings outside the Earth’s gravitational pull for the first time, orbiting the moon and sending live broadcasts from lunar orbit. “Grapevine” remained Gaye’s highest charting success until five years later, when “Let’s Get It On” reminded all the chaste ladies of the world that we’re all sensitive people, with so much to give—Gaye’s updating of Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress.” No acting coy ‘round Marvin’s smooth heat.

J. W. Bonner writes frequently for various magazines, including Asheville Poetry Review and ARGO: A Hellenic Review. His work has also appeared in Artforum and Kirkus Reviews, and his fiction has appeared in The Greenboro Review, Tyuonyi, and The Quarterly. Bonner teaches at Asheville School (Asheville, N.C.).