Against Kool: Martin Seay on “Bull in the Heather”

Reader, I have tried.

I have listened, and I have listened again. I have set aside and I have returned to, time and again, always open to the possibility that the problem is me, that there’s something I’m just not hearing.

I have even arrived at a reluctant understanding that Sonic Youth are good, to the extent that they consistently hit what they aimed at, and in the course of doing so opened new possibilities for rock music: new ways for audiences to listen, new ways for musicians to play and to speak. I admire Sonic Youth.

But I don’t like ’em, and I’m trying to figure out why.

I first took note of the band—and I don’t think this is unusual, and I do think it’s significant—in print. Sonic Youth’s music was not something that one heard on the radio in the late ’80s and early ’90s, at least not in the Houston suburbs, or in San Antonio, where I respectively grew up and went to college. I probably saw their videos on 120 Minutes or whatever, but they sailed past me, seemingly intended for somebody else.

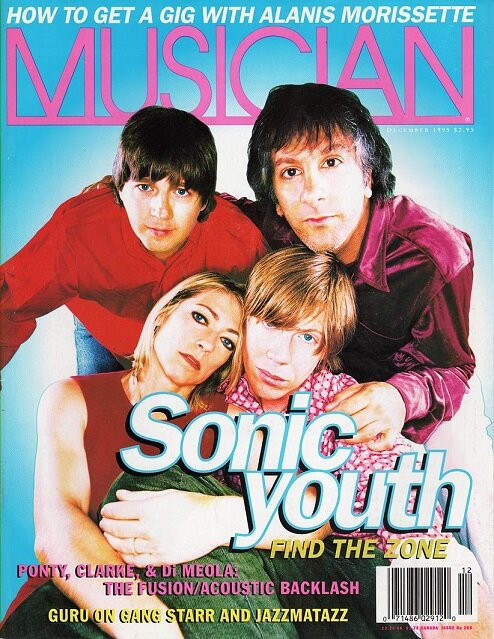

I didn’t give them any thought until I saw them on the cover of Musician, a now-defunct magazine that I read every word of every month—although I was not, and have not since become, a musician—and that still informs my understanding of art in fundamental ways. Almost uniquely among glossy music mags, Musician tried to explain what songwriters actually do, and by extension how songs actually work. So when it paid attention to Sonic Youth, I did too.

As you might expect of a magazine focused on craft, Musician didn’t have a lot to say about the punkier sorts of rock, and therefore it was a surprise to see the impassive faces of Thurston, Kim, Lee, and Steve emerge from my mailbox in late 1995. I’m pretty sure the profile was written by Mac Randall; like most of Musician’s content, it seems not to exist on the internet.

The occasion was the release of Washing Machine—an album that arguably marks the end of Sonic Youth’s punk period and their transition into more abstract territory, which is probably what put them in the good graces of Musician’s editors—but the profile opened with a detailed description of a much earlier song: “(I’ve Got a) Catholic Block,” the second track on their 1987 album Sister. Had I stumbled across “Catholic Block” by chance on a college radio station I think I would have heard a propulsive clatter held together kebab-style by a very pointy riff; my impression wouldn’t have been mistaken, but Musician took note of things that I’d have missed, or heard only as noise.

The song starts, for instance, with the static of guitar leads being plugged into and unplugged from jacks, followed by the sound of strings “tuned to some incomprehensible interval”—the phrase that really got my attention—resonating without being plucked. Although the song’s in F♯, Kim Gordon’s bassline sticks stubbornly to C♯, gesturing toward a resolution that never quite arrives. When Steve Shelley hits his hi-hats on the one and three, he keeps them wide open, yielding a beginning that sounds like an ending: a square-wheeled, inside-out pattern that’s splashy in exactly the wrong places. Stuff like that.

Anyway, I bought Sister, and Washing Machine, too. I thought they were pretty good. I didn’t listen to them much.

Sonic Youth casts a long shadow over the March Plaidness bracket—yet they’re also not an obvious candidate for inclusion, and in fact went unselected by the tournament’s 64 essayists. In an era defined by local scenes in midsized cities and college towns, they were an archetypal Manhattan band. Rather than being comfortably contained by the alternative/grunge era, their career spanned thirty years, from 1981 to 2011. (The four longest-tenured members are all Boomers, not Xers; three were born in the ’50s.) From a purely musical standpoint, their most groundbreaking and influential material dates from 1988 or earlier. Their most consequential contributions to the rise of Alternative Nation took place in the back office: they were one of the first established indie bands to sign with a major label—DGC, a subsidiary of Geffen—and they did so under terms that allowed them an impressive degree of independence. Most importantly in the Plaidness context, they also served as artists-and-repertoire people for DGC, which signed Nirvana at their suggestion.

One hesitates to put too much emphasis on single events, but this was a big one: the point at which “alternative” rock began to emerge from subculture into culture, propagated by resources and apparatus that had previously ignored it and against which it had, at least to some extent, defined itself. By January of 1992 “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was in the Billboard Top 10, Nevermind was the best-selling album in the USA, and alternative rock was no longer optional: people who hadn’t sought it out were obliged to have opinions about it anyway.

Given their role in making this happen, it seems nearly as plausible to argue that March Plaidness fits inside Sonic Youth as it is to argue the converse.

The story of Sonic Youth is, among other things, the story of a marriage. Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon were newly a couple when they started the band; it ended when they divorced.

Lee Ranaldo, to be fair, was on board from nearly the beginning—when Moore and Gordon didn’t have much more than that name, Sonic Youth—and he stayed for the duration. Ranaldo was a Long Island kid, a skilled guitarist, and a fan of Bay-Area psychedelic groups like Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead; he’d moved into the city after studying art at SUNY Binghamton. Gordon, who’d grown up in Los Angeles with stints in Hawaii and Hong Kong, had an even more intensive art-school background, a BFA from Otis; after graduation she headed east to seek her fortune among the lofts and galleries of Lower Manhattan. Moore was a college dropout from Connecticut, lured to NYC by the punk scene. Gordon and Moore both had professor fathers—his taught music and philosophy, hers was a sociologist who studied subcultures in high schools—and they both had rocky young-adulthoods: Moore’s dad died suddenly, and Gordon’s older brother has schizophrenia. Before Sonic Youth came together, Gordon, Moore, and Ranaldo had all played in other bands in an at least semi-serious way.

We should note that in downtown Manhattan circa 1980 the notion of playing in a band in a semi-serious way would have been pretty broadly interpreted. By then most of the punk and new-wave acts that piqued Moore’s interest had either faded away or outgrown the local venues. The most noteworthy bands that succeeded them were inspired by their predecessors’ ostensible willingness to discard rulebooks and instruction manuals, but were also frustrated by the music’s failure to match the rhetoric. As they (correctly) saw it, punk was retrograde, a reversion to the first-generation rock-’n’-roll of the mid-1950s, while even at its most innovative, new wave’s careerist reliance on technique left in place conventional barriers between performers and spectators. What punk had merely stripped down, these newer bands sought to throw out entirely; instead of an accord with audiences, they prioritized an expressionism that veered toward the unintelligible, personal to the point of perverseness. The resulting scene—short-lived, fractious, sporadically documented—became known as no wave.

The short version of the tale of the death of no wave goes like this: Brian Eno killed it. Eno produced No New York, the compilation that for decades constituted the most widely-available survey of the music, and he opted to include sixteen songs split evenly among just four bands; everybody who got left out was pissed, and the community collapsed. That, of course, is not the whole story. For one thing, a quick listen to any of the tracks on NNY will reveal certain, ahem, inbuilt commercial limitations working against long-term sustainability; we ain’t exactly talking about the Grand Ole Opry here.

For another, as Alec Foege points out in Confusion Is Next, his 1995 book about Sonic Youth, the no-wave scene was already plenty fragmented before Eno showed up, with the major division being between East Village bands and SoHo bands. The former, generally speaking, were primitivist, chaotic, and improvisatory; their music nodded obliquely toward blues, jazz, and funk. The latter were regarded as artier, more deliberate; they prioritized avoiding clichés—particularly the bluesy gestures that undergirded rock ’n’ roll—and sometimes adopted new systems and strategies to help them do so. East Village bands played in scuzzy clubs; SoHo bands preferred an emergent network of lofts and galleries. Without question, their mutual animosity contained an element of class conflict. The four No New York bands all came from the East Village faction.

Sonic Youth’s closest connections, at least at first, were to the SoHo faction. Ranaldo played in early groups led by Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca, both of whom were making music that emphasized massed overtones, and therefore depended on increasingly large numbers of precisely-tuned electric guitars. (By “increasingly large” I mean sometimes north of a hundred; these projects became rites of passage and networking opportunities for a bunch of up-and-coming guitarists, including members of Swans, Band of Susans, and Helmet.) Gordon was also a friend of Branca’s, and she connected Moore with him, which ultimately led to Sonic Youth’s debut as recording artists: Neutral, the tiny indie label that Branca founded and ran, released the band’s first EP and first album.

Chatham’s and Branca’s work drew from punk’s edgy energy, but like most of the SoHo artists, their creative ambitions were broader and more arcane. Chatham was a multi-instrumentalist associated with an early branch of minimal music based on long drones; Branca’s background was in experimental theater, and he regarded his rock-band projects as drama by other means. In this sense, both were representative of their milieu. A Venn diagram of the rock, jazz, modern composition, visual art, poetry, criticism, publishing, dance, theater, film, curating, and collecting then underway in Lower Manhattan would look like a rainstorm in a poorly-graded parking lot: not only did many of the participants work in multiple forms, the forms themselves tended to meld. In rare cases—Laurie Anderson, for instance—these artists have managed to resist classification for the length of their careers, generating a coherent body of work without getting pigeonholed. In even rarer cases—Madonna, for instance—they’ve managed to camouflage their underground origins while applying lessons learned among the avant-garde to command the attention of an unsuspecting bourgeois public.

Whether they picked it up in art school or by osmosis, the SoHo crowd seemed to share an emphasis on audience reaction over artist intention: what a particular work is and does was regarded as less interesting than what an audience might make of it. In short, it was a great time to be a critic. Being a critic and an artist was even better, given that the lines between the two had become very smudgy indeed. Here, for instance, is an excerpt from “I’m Really Scared When I Kill in My Dreams (from a Lyric by Glenn Branca),” an often-cited—but not often cited at length—and rather striking essay that appeared in Artforum in January of 1983:

The club is the mediator or frame through which the music is communicated. The band literally plugs into the technology of the club in order to magnify the sound, turning a possibility into actuality, making what is heard by the musicians themselves accessible to an audience. People pay to see others believe in themselves. Many people don’t know whether they can experience the erotic or whether it exists only in commercials: but on stage, in the midst of rock ‘n’ roll, many things happen and anything can happen, whether people come as voyeurs or come to submit to the moment. As a performer you sacrifice yourself, you go through the motions and emotions of sexuality for all the people who pay to see it, to believe that it exists. The better and more convincing the performance, the more an audience can identify with the exterior involved in such an expenditure of energy. Performers appear to be submitting to the audience, but in the process they gain control of the audience’s emotions. They begin to dominate the situation through the awe inspired by their total submission to it. Someone who works hard at his or her job is not going to become a “hero,” but may make just enough money to be able to afford to be liberated temporarily through entertainment. A performer, however, as the hero, will be paid for being sexually uncontrolled, but will still be at the mercy of the clubs and of the way the media shapes identity. How long can someone continue to exert intensity before it becomes mannered and dishonest?

The author of the piece, you will not be surprised to learn, is Kim Gordon; it’s one of several she wrote around that time, while also playing gigs, making art, and scraping by on odd jobs. Her aphoristic statement “People pay to see others believe in themselves”—in her 2015 memoir Girl in a Band she archly calls it a line “that the rock critic Greil Marcus quoted a lot”—is best read in context, where it’s easier to catch the full range of its awkward implications about authority, authenticity, and the way a piece’s content is jointly generated by performers and spectators.

In a way, this loosening of constraints and diffusion of control was itself a callback to the mid-’50s: not to the birth of rock-’n’-roll, but to the early days of free jazz, when improvisors began exploring how many seemingly indispensable aspects of their craft they could jettison without losing the coherence of their music. (Ornette Coleman: “It was when I realized I could make mistakes that I decided I was really on to something.”) Even shorn of regular rhythm and conventional chord changes, a forceful and deliberate performance could succeed by persuading its audience—well, at least some of its audience—to help make sense of the music by listening perceptively and creatively.

No wave often sounded more like amplified free jazz than punk, and the way it worked was similar, if not quite the same: those in the crowd who chose to stick around and tough it out would reliably take on the task of finding things to appreciate, or at least to take note of, amid the chaos. As Gordon’s essay suggests, the forcefulness of these bands empowered their audiences, but not necessarily through the kind of communitarian mutual uplift you’d see at, say, a Minor Threat show. Instead, it empowered them as interpreters—or maybe as connoisseurs, as Gordon’s slightly clinical tone suggests. Depending on the band, and depending on the audience, it might elevate the power of interpretation above the power of the performance.

Even at its most expressive and passionate, no wave had to stay ahead of its audiences’ expectations, and therefore had to be a little calculating. One common strategy was to avoid standard musical techniques and/or tunings, or just to never learn the “proper” way to play in the first place, an approach favored by many on the art-school-to-rock-band track. Gordon, for instance, still frequently asserts that she “doesn’t consider herself a musician” despite having gigged regularly and remuneratively for forty years. Coming from a major figure in alternative rock this may sound like a preposterous affectation, but it’s one you hear fairly often in a no-wave context. While most of those bands flamed out too soon to put anybody in peril of developing chops, those who stayed in the game inevitably gained some kind of facility on their instruments, even if they persisted in tuning them only by feel, or in playing them “wrong”: scraping and whacking and maiming their guitars, letting them feed back, jamming objects under the strings, and so forth. Musicologists have a name for such unorthodox methods; they call them “extended techniques.” A player might start doing stuff like this spontaneously, in a moment of inspiration and/or agitation, but when they try to repeat the effect later it becomes something else: a technique. You see how this stuff works.

Which brings me to “Bull in the Heather.”

In its wisdom, the Selection Committee chose “Bull in the Heather”—the best song from one of Sonic Youth’s least interesting albums, 1994’s Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star—to represent the band on the March Plaidness longlist. It’s a smart pick, for a lot of reasons. First, it’s a concise representation of what SY is all about: weird, dissonant, and sinister, but also nimble, catchy, and fun.

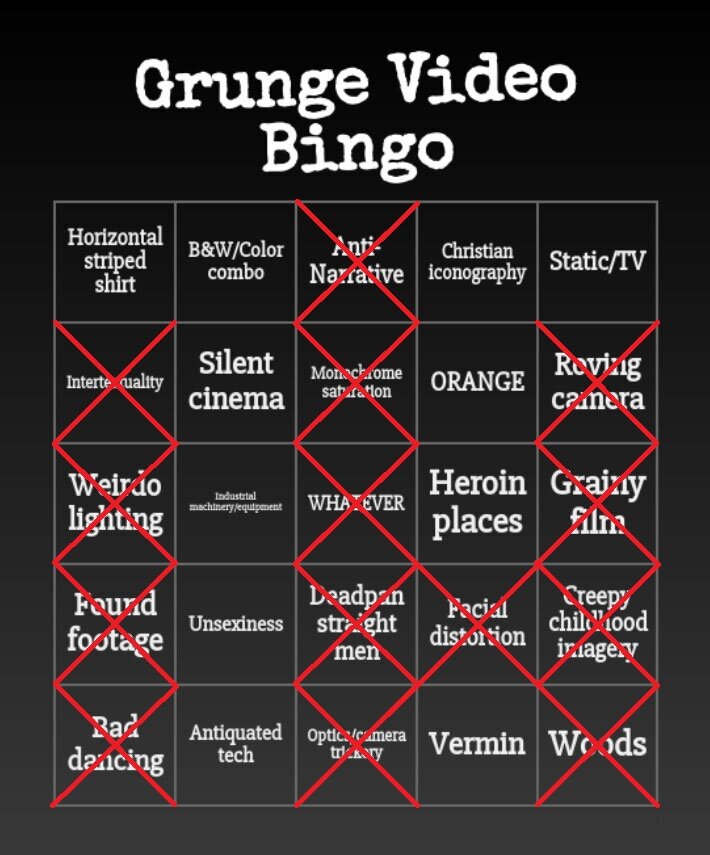

It has a great video, too, directed by frequent collaborator Tamra Davis—who’d go on to helm Billy Madison and the Britney Spears vehicle Crossroads—and it famously features some top-notch winsome frolic by alt-rock culture hero Kathleen Hanna, a founder of the band Bikini Kill and the zine Riot Grrrl, whom history records as the origin of the phrase “smells like Teen Spirit.” Hanna’s appearance checks the “intertextuality” box on Will Hansen’s grunge video bingo card, but “Bull in the Heather” doesn’t even need it for bingo:

Most intriguingly, the song is a relic of the fraught moment when alternative rock’s ascent into the stratosphere had begun to falter and careen: the big labels were binging indiscriminately on soundalikes in the wake of Nevermind’s multiplatinum success, while high-profile releases by established indie crossovers—including SY’s previous LP Dirty, and for that matter Nirvana’s In Utero—were underperforming expectations. Sonic Youth read the room, sidestepped the pressure to expand market share, prioritized retaining their cred, and basically made a Pavement record: relaxed, slapdash, undercooked, a little silly. “Slacker” is not a vibe that the industrious sophisticates of SY can convincingly sustain, and the album isn’t great. Nevertheless, retreat-and-regroup was a canny move, especially given the stakes and the perils: DGC released “Bull in the Heather” as a single two weeks after Kurt Cobain died.

So what are we hearing here? Well, right off the bat, extended techniques: Moore plays his opening riff with harmonics—picking strings while touching them lightly in precise spots to produce chiming overtones but not the fundamental pitch—and he intersperses some quick strums behind his guitar’s bridge, a move of which the Fender Jazzmasters that he and Ranaldo favor are particularly susceptible. Moore is also using one of the non-standard tunings for which Sonic Youth is renowned, in this case (the internet informs me) G G D D D♯ D♯. That tuning of adjacent strings to the same pitch is a favorite Glenn Branca trick: it produces a droning effect, plus the sort of shimmer associated with twelve-string guitars, mandolins, and other coursed instruments. The overall result sounds a bit like the intro riff to “Gimme Some Lovin’” performed by evil marionettes. While Moore is doing his thing, Gordon is summoning whales by scraping her pick along the strings of her bass, and Ranaldo is engaged in some scraping of his own, with a delay pedal contributing additional eeriness.

Then … maracas!

Okay, here’s the deal: although alternative rock tends to be characterized in terms of the electric guitar’s resurgence over the synthesizer, it is no less a tale of the trap set’s revenge on the drum machine. Dave Grohl, Georgia Hubley, Matt Cameron, Britt Walford, Phil Selway, Jim Eno (I’m from Texas; Spoon is a ’90s band), et al. did as much as anybody to shape the sound of the era, and Steve Shelley, a later but crucial addition to the Sonic Youth lineup, belongs on that list too. SY cycled through a few distinguished bashers in their early days—jazzy/funky Richard Edson, punky/rocky Bob Bert, heavy/bluesy Jim Sclavunos—and while they recorded cool stuff with all those guys, the band didn’t quite click as a stable unit until Shelley came along. Although his punk credentials are impeccable—he was a founding member of the Michigan-based Crucifucks, one of those names that almost obliges whoever came up with it to start a band—Shelley’s heart ultimately belongs to Ringo, which makes him simpatico with his three SY bandmates, all of whom harbor a fascination with ’60s pop culture, particularly when it’s evil, disreputable, and/or embarrassing.

The drums and percussion on “Bull in the Heather” could have been lifted straight from any number of British Invasion hits. For fifteen seconds or so, the song turns into a breezy little bop for cruising down the autobahn. Then tension creeps back in as the first verse starts, by way of woozy, meandering melodies on both guitars. (If you’re planning to try this in your garage, Ranaldo’s tuning is G G C G C D.)

Gordon’s congested alto doesn’t exactly put listeners at ease, either. “Ten, twenty, thirty, forty,” she sings, tacking a decimal place onto the typical rock-’n’-roll count-off, along with three weak-rhymed unstressed syllables: a heartbeat-flutter under the rhythm. It’s not clear what she’s counting—cash? time? distance?—but it’s adding up in a hurry. Those repeated “-ty”s grid out into the symploce of the next lines—“Tell me that you […] me”—made increasingly urgent by the imperative mood and their breathless, insinuating tone. Gordon is Sonic Youth’s principal scholar of hard-boiled fiction and film noir, and in “Bull” she’s speaking in the voice of a femme fatale, suggesting a sadomasochistic entanglement with some brutish antihero who wants (or whom she wants to want) to both “hold” and “whore” her. True to form, she also prompts us to wonder about the extent to which her narrator’s performance is for our benefit as well as the imagined lover’s: the great line “Tell me that you’re famous for me” abruptly casts what had seemed like an intimate or even secret exchange before the public eye.

What is this song about? Well, strictly speaking, it’s about a racehorse, a 29-to-one longshot that won the Florida Derby in 1993. Even more specifically, it’s about a bumper sticker about that racehorse, a gift that Sonic Youth got from Pavement utility player Bob Nastanovich, a confirmed thoroughbred obsessive. Probably nobody in Sonic Youth gives much of a damn about horseracing—apart from an oblique reference to luck, the verses don’t mention it—and therefore we should take “betting on the Bull in the Heather” as a metaphor. But for what?

While doing publicity for Experimental Jet Set, Gordon told New York magazine that the song is about “using passiveness as a form of rebellion—like, I'm not going to participate in your male-dominated culture, so I'm just going to be passive.” If we take her at her word, then we can read the racehorse’s strategic last-minute surge out of nowhere as a feminist parable about waging asymmetric warfare against patriarchal oppression. If we stick to the text of the lyrics, the analogy lands a little differently: come-from-behind winner as ostensible submissive topping from below.

The ambivalent figure of the femme fatale gained fresh currency in the early ’90s, adopted in some cases as an icon of empowered sex-positive feminism, exploited in others as the same misogynist projection that we find slinking through midcentury films and pulp novels. It occurs to me that listeners who come searching for either trope in “Bull in the Heather” can find it there. In other well-known Sonic Youth songs sung by Gordon—“Pacific Coast Highway,” “Kissability”—she adopts the persona of a harasser or predator, a rhetorical move that feminist fans can take as a way to make shitty male behavior visible and subject to censure. Then again, shitty male listeners can hear these same songs and be titillated by the idea that Gordon’s adoption of their creepy speech constitutes acceptance of it, or even tacit endorsement of it via her identification with or eroticization of the oppressor. The songs support both readings, and consequently can appeal to both sets of prospective fans—though significantly it does not seem likely to serve as an opportunity for those two sets of fans to negotiate their differences. (Gordon pulls off something even trickier in “Kool Thing,” SY’s collab with Chuck D from 1990’s Goo: as she herself points out in Girl in a Band, it’s ultimately impossible to say whether the song is a critique of sexism in hip-hop, or sendup of a white girl’s radical-chic fetish for rap stars, or both, or neither.)

Gordon has done a lot of hard thinking about audience reception, so it’s clearly not an accident that this keeps happening: it’s what these songs do, how they work. This undecidability is impressive as an end in itself, yielding complex results that reward closer examination. It’s also a means of having it both ways: drawing in listeners who hold contradictory values, while at the same time foregrounding the songs’ ambiguity in order to maintain inscrutable agency by way of listeners’ recognition that their preferred interpretation isn’t the only one.

Not unlike an extended technique, this ambiguity loses some of its effectiveness when it becomes expedient or rote: a default mode. In Girl in a Band, Gordon detours to take a shot at Lana Del Rey, “who doesn’t even know what feminism is, who believes it means women can do whatever they want, which, in her world, tilts toward self-destruction. […] Does she truly believe it’s beautiful when young musicians go out on a hot flame of drugs and depression, or is it just her persona?” It’s an interesting question, but it’s also hard to shake the sense that Gordon’s discomfort lies less with Del Rey’s lack of feminist rigor than with her pronounced willingness to commit to the bit.

I’m starting to figure out what bugs me about this band.

In Confusion Is Next, Foege pegs Sonic Youth with a wince-inducing but apt tagline: “the band that has cool cornered.”

In their 2000 book Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude, Dick Pountain and David Robins propose as a “rough working definition” of cool “a permanent state of private rebellion” (italics theirs). Notwithstanding the authors’ caveat that cool is intrinsically resistant to being defined, this is honestly pretty good, encapsulating as it does Marlon Brando’s iconic statement of purpose in The Wild One. (“Hey, Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” “Whaddya got?”) The permanent nature of the rebellion means that it’s detached from aims: it can never completely succeed or fail. Because the rebellion is private, even if it did have specific demands, those demands wouldn’t or couldn’t be completely articulated. Cool can be understood as a kind of perpetual adolescence—a kneejerk resistance to authority coupled with an abiding investment in one’s own subjectivity—which helps explain why a band that prioritizes being cool might, say, have “youth” in its name.

The resistance to definition that Pountain and Robins warn of is in fact exactly the point of cool, and exactly the problem. “Cool is not a collective political response,” they write, “but a stance of individual defiance, which does not announce itself in strident slogans but conceals its rebellion behind a mask of ironic impassivity.” (Cf. Gordon’s “using passiveness as a form of rebellion.”) While the private character of cool’s defiance places it outside politics, its permanence—the fact that it has no demands that can be met apart from the aesthetic and hedonic—puts it largely outside ethics, too. When Humphrey Bogart turns Mary Astor over to the cops in The Maltese Falcon, or when he tells Ingrid Bergman to board the plane in Casablanca, the audience is moved not because what he’s doing is right (although it is), but because what he’s doing is cool—as is, crucially, the way he’s doing it. The coolness is what sells us on the rightness, what makes it appealing. The rightness does not reside within the coolness, however; the coolness can get along just fine without it.

As Casablanca illustrates, while political commitment may be anathema to cool, cool was refined and propagated in a particular ideological context. As a component of pop culture it’s largely a Cold War phenomenon, and its classic manifestations—abstract expressionism, bebop jazz, serialist composition, existentialist literature—were deliberately amplified by American propaganda apparatus as an appealing individualistic alternative to communist collectivism. Perhaps needless to say, cool doesn’t readily lend itself to nationalistic purposes, and American democracy has never quite figured out what to do with it.

American capitalism, on the other hand, has known exactly what to do.

Of what does Sonic Youth’s coolness consist? Two things, principally. The first is connected to the “mask of ironic impassivity” that Pountain and Robins mention, though there’s both more and less to SY’s irony than may initially meet the eye. Theirs isn’t a laconic façade that protects inner sensitivity and sentiment à la Lester Young or Paul Newman, nor is it the acid omnidirectional disgust of Lenny Bruce or Johnny Rotten. Instead, Sonic Youth were practitioners of a postmodern style of irony, one that probably originated with Andy Warhol, and that later came to dominate the ’90s, thanks in no small part to SY’s influence. It’s a style that partakes of punk skepticism but not punk anger, and that even more notably one-ups the self-protective function of midcentury cool by dispensing with the implication that there’s much in the way of a stable self to protect. This is scare-quote irony, the shopping-mall-food-court cousin of the deconstructionist tactic of putting certain terms “under erasure”—i.e. striking them out but leaving them legible—when one wants to use them without taking full responsibility for using them. This is irony that seeks to have it both ways.

In his landmark 2001 indie-rock survey Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad recounts a 1985 interview in which the members of Sonic Youth apparently disagreed among themselves about whether the cover of the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” that appears on their debut LP Confusion Is Sex was sincere or tongue-in-cheek. (Ranaldo argued for the former, Gordon the latter.) The band later fielded similar inquiries about other pop-culture references—from the Creedence nod in the title of Bad Moon Rising to the Madonna covers and hip-hop pastiche of their Ciccone Youth side-project—but journalists gradually learned to avoid that particular quicksand patch: the joke was always on them, either for taking the band’s gestures too seriously or for not taking them seriously enough. At its best, as discussed above, the ironic concealment of artist intent engaged fans more intensely by honoring their role as interpreters. When done repeatedly and automatically, however, it gives the impression of a band that always keeps its weight on its back foot, never making any assertion of value that it can’t strategically evacuate. What I’m unable to avoid saying—and I hope you can forgive me for this—is that irony is the shackles of Youth.

The other main component of SY’s cool is connoisseurship. In Cool Rules, Pountain and Robins point out an ostensible paradox, namely cool’s tendency to resent conventional society for sneering at subcultures while itself being hyperjudgmental about subcultural expressions that it views as inauthentic, inept, clueless, or out of date. The apparent contradiction is, of course, easily explained by the fact that always we base our verdicts on lots of criteria. We make moral and ethical decisions according to fixed principles, whereas aesthetic assessments are fun precisely because the targets move. The mainstream, by definition, rewards conformity in cultural matters, while cool prizes novelty, originality, exclusivity—hipness, if you prefer, in the sense of being hip to the latest shit.

Sonic Youth were unfailingly hip to the latest shit. They weren’t shy about advertising it, either. Take, for example, the music video for “Teen Age Riot”—the opening track from Daydream Nation—for which the band is credited as director:

In addition to some pretty standard concert and b-roll footage, the video is littered with citations: blink-and-you-missed it clips of the band’s friends and heroes, some of whom were pretty obscure in 1988 (and all of whom were less so by the mid-’90s, thanks in large part to Sonic Youth). When I first found the video on YouTube, it reminded me of the famous-in-some-circles “influences list” included with the 1979 debut album by the British avant-garde group Nurse with Wound, with, I realized, one huge difference: the Nurse with Wound list is just that, a printed list, and it therefore equips the vanishingly small portion of the population inclined to do so with the key information they need to track the obscure artists down. The clips in the SY video don’t give us any leads; they’re just an occasion for hip fans to congratulate themselves for spotting the references, and for the band to show off its curatorial acumen. The Nurse with Wound list is nerdy; the “Teen Age Riot” video is cool. (Both, to be clear, are obnoxious.)

It’s notable that SY took pains to include peers and pals like Lydia Lunch, J. Mascis, Mike Watt, Ian MacKaye, and Henry Rollins in the video, because it is almost impossible to overstate the degree to which the band was connected to other prominent creative folks, and to which their career was shaped by such connections. This was mostly Gordon’s doing, at least in the early days, and therefore the art-world ties were closer than those to the music world (although Danny Elfman—yes, that Danny Elfman—was Gordon’s first serious boyfriend in high school). Her entrée to the SoHo scene, for instance, came via her mentor Dan Graham; when she drove to New York from California she carpooled with her friend Mike Kelley; upon arrival she crashed with Cindy Sherman; later she sublet a corner of Jenny Holzer’s loft. These people were not particularly famous at the time.

That’s a big part of what made Sonic Youth sustainable: instead of seeking help from friends in high places, their networking was largely lateral and organic. (Their only real A-list advocate was Neil Young, and the series of shows that they opened for him in 1991 was mostly a disaster.) I say “largely” because the networking wasn’t subtle, and verged at times on pushy. Gordon’s Artforum piece on Branca, for instance, came out about a month before Branca’s label released the first SY album. When the band decided that the best way to become a national act was to get signed by the California-based indie label SST, they initiated a charm offensive that included writing “Hello to Black Flag”—the band that SST founder Greg Ginn led—“from Sonic Youth” on the wall of every green room in every venue they played.

But although SY weren’t above instrumentalizing their connections, they also distinguished themselves as an investment with a good rate of return. While the band capitalized on early buzz generated by their associations with art-world up-and-comers like Kelley, Tony Oursler, James Welling, Judith Berry, Richard Kern, Gerhard Richter, Charles Atlas, Todd Haynes, Richard Prince, et al.—all of whom allowed SY to use their images or worked on SY videos—it’s also clear that the artists, many of whom were musicians themselves, got a kick out of messing around with indie rock. It didn’t exactly hurt their careers, either. While it’s possible that Gordon is just very good at picking winners—maybe she should have gotten into thoroughbred racing!—it seems rather more likely that these artists benefitted from associating with the hip indie-rock band that discovered Nirvana. I’m not sure what it would have cost to buy one of the Richter candle paintings that appear on the Daydream Nation sleeve when the album came out in 1988, but suffice to say it would have been less than the $16.6 million that a work from the series sold for in 2011.

The band applied this mutual-back-scratching approach to its relationships with other musicians, too. Moore in particular was inspired by hardcore punk, and although the other members of SY didn’t totally connect to the music, they were all duly impressed by the self-sustaining network of bands, labels, venues, fanzines, and people with spare couches that constituted and vitalized the hardcore scene. They also understood that the model was transferrable to other types of music, and scalable to some degree. This led to what’s arguably the most admirable and enduring of Sonic Youth’s achievements: their exceptionally good indie rock citizenship. Neither mercenary nor uncritical—mention Billy Corgan’s name to a former member of SY and watch what happens—they took pains to scout interesting younger bands and help them reach wider audiences by featuring them as opening acts, producing their recordings, and in some cases releasing their albums; Shelley and Moore respectively founded the indie labels Smells Like Records and Ecstatic Peace! (exclamation point Moore’s).

Some of these younger acts sounded quite a bit like Sonic Youth, and some of them ended up being very successful. Not many of the successful ones sounded much like Sonic Youth, though, which adds weight to the argument that SY’s most enduring influence is curatorial rather than musical or inspirational.

It occurs to me that the economics of the whole Sonic Youth project may actually reflect this. In Confusion Is Next Foege includes a quote from a DGC exec that almost slipped past me, about how Sonic Youth “can bring things to the label in an A&R capacity […] and they will be given credit for that, in terms of points,” i.e. a percentage of sales revenue. Sonic Youth, as you’ll recall, brought Nirvana to DGC, and Nevermind, as you probably know, is one of the best-selling albums of all time, with something like 30 million units in circulation. A tiny percentage of the sales of 30 million albums still comes out to a shit-ton of money. If I’m inferring correctly, this casts SY’s increasingly experimental late- and post-’90s work in a somewhat different light, or at the very least suggests that they were making artistic decisions with a different set of financial considerations than other working bands of comparable prominence.

SY definitely evolved over the years, in ways that generally made them better. To their credit, they seem to have recognized early on that their signature postmodern irony came with limitations, and they addressed the problem posed by this aspect of their coolness by doubling down on the other major aspect of their coolness, namely their connoisseurship. If they couldn’t quite manage the no-safety-net intensity that comes from unselfconscious commitment to an idea or a performance, then they could do what they do best: cite that commitment.

Tellingly and typically, this citation sometimes required bringing in hired guns. The best thing SY did prior to recruiting Steve Shelley is “Death Valley ’69” from Bad Moon Rising, and the best thing about it is the unhinged, ecstatic guest vocal from Lydia Lunch, who cowrote the song with Moore. While SY’s three singer-songwriters are all effective in their own ways—Ranaldo’s clear tenor is sweet and engaging, and Gordon has developed a bunch of pungent timbres within the constraints of her range—it’s impossible to imagine any of them risking embarrassment the way Lunch does here. In the “Bull in the Heather” video, it’s equally impossible to imagine any member of the band goofing around as resplendently as Kathleen Hanna does. (Gordon gets a dispensation from cavorting for being pregnant at the time … but compare, if you will, the scenes of Hanna’s prancing to Moore’s and Ranaldo’s imagined reenactment of a teenage punk-rock bedroom: goofing around versus “goofing around.”) It’s not only wild abandon that SY outsources; sometimes it’s fussy, dorky attention to detail that they’re unable to reconcile with their default stance of shoot-from-the-hip nonchalance. Unpopular opinion, maybe, but for my money the three best SY albums are the ones they did with post-rock polymath Jim O’Rourke: NYC Ghosts & Flowers, which he co-produced, and Murray Street and Sonic Nurse, on which he’s credited as a fifth member. O’Rourke’s perceptive ear and steady editorial hand activated compositional possibilities that had previously been inert or fleeting, capturing SY’s noisy weirdness at its most effective and affecting while yielding some of their best songs.

Of course, for their citational strategy to work, Sonic Youth needed an audience that caught the references, and appreciated them as references. Back in the lofts of SoHo this problem took care of itself, but SY knew they had prospective fans among the sarcastic clove-smokers of every midsized college town, and they wanted to reach them; thus their longstanding and awkward entanglement with the world of music writing. As we’ve seen, Gordon had done serious arts criticism as SY was taking off, and she certainly knew how to talk to critics and music journalists; Moore, on the other hand, was a punk-rock fanzine guy who didn’t hesitate to vent his pique at the rock-critic establishment by, say, calling out music editor Robert Christgau in angry letters to the Village Voice and in the lyrics to “Kill Yr Idols.” Gordon’s and Moore’s good-cop/bad-cop routine doesn’t seem to have been calculated—their behavior squared with their respective temperaments—but it was certainly effective, assisted no doubt by the fact that approximately zero rock critics want to be known as “the establishment.”

In Our Band Could Be Your Life, Azerrad quotes early SY drummer Bob Bert on this topic:

One thing Sonic Youth always did, almost to a gross point, was that they always knew who the hot journalists were and they always became really close. […] You’d go to a party and Kim would know who the Village Voice writer was in the corner of the room and she’d make sure she went over there. They were really good at schmoozing in every respect. They always made sure they met as many popular, famous people as they could, whether it be the art world or the music world. They were always really good at that—they always knew who to meet, who to know.

Does Bert have axes to grind? Sure. Is his account consistent with the available facts? Absolutely. Okay, but, I mean, c’mon, we’re not talking about jury tampering here. Is there anything actually wrong with a band working the refs? Well, that depends.

Christgau eventually came around. Robert Palmer—the chief pop critic for the New York Times during the ’80s, not the “Simply Irresistible” guy, although of course there’s an SY connection to him too—was another big supporter, featuring the band as a kind of evolutionary apex of guitar music in his Rock & Roll: An Unruly History, the companion book to a major PBS/BBC documentary series. Sonic Youth also formed a lasting friendship with the inimitable Byron Coley, a longtime Forced Exposure editor whose Father Yod label occasionally issued joint releases with Moore’s Ecstatic Peace!, an arrangement that would surely make the staffers of the Rock Criticism Accountability Office—if there was one—sweep all the papers from their desks and jump out their windows.

The publication that was probably Sonic Youth’s most consistent champion during their later career is the great UK experimental music magazine The Wire, for which Coley is a regular contributor; it has put SY or its members on its cover six times, and has twice picked its albums for the top spot on its Records of the Year list. Notably, it adopted SY as a cause starting around the time “Bull in the Heather” came out, just as it was becoming clear that the wheels were coming off the alternative-rock bus, and that the future of guitar-based music lay in increasingly discrete and commercially irrelevant niches. The pages of The Wire documented Sonic Youth’s gradual reframing, from venerable indie rockers to protagonists in various avant-garde currents ranging from minimalism to free improv to freak folk.

That’s not to suggest that the magazine’s coverage of the band has been hagiographic, or less than insightful. Way back in 1989, Chris Bohn—writing under his nom de plume Biba Kopf (this was a thing people did in the indie-rock era)—profiled Sonic Youth in the wake of the attention they’d garnered for Daydream Nation:

Live, Sonic Youth’s excitement is generated by the hectic activity in the music’s overtone layer […] the result of guitarists Ranaldo and Moore atomizing the song’s harmony, each one subsequently attacking a severely restricted area of the scale while playing tag with the melody and all the while striking up o-tones that pattern and cluster in ever more unpredictable combinations. Once upon a time I’d interpreted Sonic Youth’s excitement according to the level of noise they created. Rather it is its opposite, the harmonic overload, that is responsible for its immense erotic pleasures, even if the final result is not that dissimilar in effect from that caused by the friction of noise.

That’s a smart analysis, one that accomplishes the important and unfortunately uncommon task of pointing out how and why Sonic Youth sounds different from other loud guitar bands. It’s also a distinction that helps trace them back to a cohort, specifically the SoHo no-wave musicians who split from the East Village faction by abandoning Dada atavism to seek out new ways to organize sound.

In fact, Bohn’s analysis may be a little too good. To be sure, Bohn is writing here about SY as a live act, and I never saw them live—certainly not when Bohn did, in the late ’80s, in packed clubs where volume and feedback can produce acoustic phenomena that recordings never quite do justice to—but I’m still skeptical. I buy his description as accurate; I just think it seems pat, particularly the implication that the band is making choices in the moment to produce the effects that he’s describing, the way that jazz players might. That seems unlikely; I think they’re just rocking out. The harmonic overload that Bohn hears is no accident, but the major decisions that generated it were probably made much earlier. Ranaldo and Moore are playing in “a severely restricted area of the scale” mostly because their guitars are tuned to drone intervals that encourage such restriction. A lot of the extended techniques they favor—harmonics, feedback, playing behind the bridge, etc.—have the effect of isolating upper partials. What SY is doing is cool and innovative, and there’s always a fine line between technical and compositional, but Bohn seems to put their approach closer to the latter than I would.

This probably seems like splitting hairs, and I guess it is, but what bothers me is that Bohn’s description does seem like a very good fit for the performances of Glenn Branca’s and Rhys Chatham’s guitar ensembles, performances that did focus tightly on building up earsplitting crushes of overtones. (Branca’s symphonies in particular give the impression that somebody figured out how to tease melodies out of the sound of a piano being dropped from a helicopter.) An obsessive interest in overtones eventually led both composers in the same direction, toward large numbers of modified electric guitars played in very particular tunings, because the effects they were after just weren’t achievable with two or three guitars, regardless of how they were tuned.

For most of its existence Sonic Youth was a four-piece rock band, with sixteen strings to work with. But Bohn knew that they were closely associated with Branca, and that Ranaldo and Moore had played in Branca’s and Chatham’s ensembles, and I think he was inclined to hear them in the context of those associations, and to write about them in a way that connected those dots. To his credit, he listened perceptively and creatively, exactly the way the SoHo no-wave bands relied upon their interpreters to listen. To be critical, and probably a little unfair, I think Bohn may have gotten Sonic Youth’s performance mixed up with its press release.

What bugs me about this band is that they get a lot of credit they didn’t earn.

In May 2009, in the depths of The Wire’s reviews section, there appeared a brief assessment of a tribute album to seminal krautrock band Neu! (exclamation point Neu!’s). The author of the review was Mark Fisher. Today, four years after his untimely death, Fisher is a beloved and influential theorist of the radical left; in 2009 he was a struggling university lecturer, a freelance music writer, and a blogger of some renown in the waning days of an era when blogs still mattered.

Fisher did not dig the Neu! tribute, panning it as an “exercise in rearview mirrorism” that betrayed the innovations of its honoree. He didn’t stop there. Noting that the album’s contributors included legacy indie-rock acts like Primal Scream, Oasis, and (of course) Sonic Youth, he asserted that these bands

all played their part in making this kind of retro-necro acceptable. As the most ostensibly credible of the bunch, Sonic Youth should arguably bear the most blame (indeed, if one were to locate the point at which rock modernism lapsed into curatorial postmodern pastiche, you could do worse than cite something like Bad Moon Rising).

Within a certain small but extremely active sector of the blogosphere, it was as if somebody had just nuked the moon. People could not fucking believe that Fisher had just written off SY—those uber-hip stalwarts of the far-out—as regressive, and that he’d done so in such a sweeping fashion. While prior to that point many reviewers had respectfully noted that the band’s recent albums principally succeeded at, um, being Sonic Youth albums, Fisher’s readiness to cast doubt on the integrity of their entire output since 1985—before their DGC sellout phase, before their Daydream Nation breakthrough, shit, before Steve Shelley even joined—was A Very Big Move, clearly intended to be provocative, and provoke it did.

Fisher’s not wrong. When I became aware of the kerfuffle via his k-punk blog, I was surprised by my own elation at hearing somebody call bullshit on Sonic Youth. Not just elation, but relief. Up to that point, I hadn’t been aware of the extent to which I’d felt guilty for my failure to connect with the band’s work, to ever manage to get excited about it.

But SY, of course, is a cool band, and this is how cool operates. The whole point is to not get excited, and to give an impression of arcane exclusivity in order to engender—especially among sincere dorks like me, who expect to get excited about stuff that is good—a sense that one is missing something. And I was missing something, because I was looking for it in the music, when in fact it resided in, and largely consisted of, the hype. “[N]o-one, even their own supporters, really expects SY to provoke any sort of strong affect at all, just elicit a bland admiration,” Fisher writes in a follow-up post. “This renormalisation of boredom, this re-establishment of consensus around ‘accepted standards,’ is precisely what is so pernicious about Sonic Youth now.”

I’m somewhat more forgiving of the band than Fisher was. Having evidently rightsized my assumptions, I now find that I am better able to appreciate SY’s careful cultivation of aura and buzz—which we can and should understand as a huge, indispensable component of their entire project—even as the music’s shortcomings become more apparent.

Let’s be clear about those shortcomings. SY’s major problem was the fact that their most dominant personality and most prolific songwriter was also their weakest singer and worst lyricist. I am 100% convinced that at any given moment during the thirty years of the band’s existence, every high school in America contained at least one kid, and probably more than one kid, who routinely wrote better lyrics than Thurston Moore, just while killing time during detention or whatever. Even the lines that are most frequently cited as evidence in Moore’s favor—“We're gonna fire the exploding load in the milkmaid maidenhead,” e.g.—prove the opposite point. The dude’s output is just jaw-droppingly awful at every turn. Of course, because Sonic Youth is unfailingly cool, Moore always has an out: maybe the lyrics are supposed to be bad, huh? You ever think of that?

In fairness, Moore can indeed write a catchy riff, and as we’ve seen with “Bull in the Heather” he’s particularly gifted at constructing such riffs out of unlikely, dissonant materials. Lee Ranaldo is a legitimately good songwriter; to my ear, most of the transcendent, scalp-tingling moments in SY’s oeuvre (there aren’t many) are his doing. And Gordon’s contributions seem progressively more impressive with the passage of time; just being a “girl in a band” (as her memoir has it) in the indie-rock era was notable in itself, but more specifically she demonstrated how to hold center stage on her own terms, simultaneously disclosing and withholding, developing a rhetoric of performance that turned potentially oppressive audience expectations to her advantage.

That’s all great. But set aside, just for a moment, the self-mythologizing, the high-art affectations, the well-earned rep as connectors and tastemakers, and just listen to the recordings. I think you’ll find yourself left with a loud indie-rock band that emphasizes timbre over melody. That’s it. That’s not nothing, but it ain’t exactly a thunderclap disruption of post-Reagan popular culture, either.

I mean, let’s just try to peek through the mists for a second. Once upon a time a four-piece rock ’n’ roll band with a fifty-percent-female rhythm section emerged from the cutting-edge New York art scene, immediately distinguishing itself through its confrontational attitude, its noirish sensibilities, and its prodigious use of droning, dissonant tunings. The year was 1967; the band was the Velvet Underground. Almost everything that’s distinctive about the sound of Sonic Youth is already fully in place on the Velvets’ early recordings. Sonic Youth were innovative, sure, but their innovations amounted to a gathering-in, not a pushing-out: they took some outré elements of the VU’s music and naturalized them, making them intelligible and palatable within the confines of indie rock. By Daydream Nation, in fact, they’d found other ’60s-era weird-tuning icons to productively borrow from: the Laurel Canyon folk-rockers and Bay Area psych bands that Ranaldo and Gordon had grown up listening to, people like the Byrds, CSNY, and Joni Mitchell. (Ranaldo name-checks Mitchell on Daydream.) SY’s innovative take on that material was simple: use the tunings and some of the chords, and play them vastly louder.

This is one of the aspects of Sonic Youth’s music that Fisher finds most objectionable, key evidence of their hidden conservatism. “Punk and postpunk’s significance was to have overcome the Sixties, to have fingered the Sixties as the problem,” he writes, “whereas SY […] re-established a continuum between punk and the Sixties, mending the bridges that punk had incinerated.” Here too I’m somewhat more forgiving; I don’t need (or want) all my music to be radical, and I can see some aesthetic value in merging techniques from two different eras.

My gripe is with the scrim of mystificatory bullshit that surrounds the band, with the fact that Sonic Youth still gets widely praised for being challenging and boundary-pushing when they were in fact mostly the opposite: translators of avant-garde material on behalf of a snobbish but conventional rock audience. And even that’s not the worst thing about them. The worst thing is that their cool substitution of ironic detachment for revolutionary commitment—of citational pastiche for legitimate innovation—encourages their audiences to congratulate the band and themselves for a venturesome catholic audacity that none actually exhibits or can plausibly claim.

Permit me two last quotations from the goldmines that are Fisher’s k-punk posts: Sonic Youth’s widely-insisted-upon status as an “experimental” band, he asserts, is only meaningful “in terms of brand identification, not in terms of any formal properties.” Elsewhere he writes that the idea that “there is a mainstream which repudiates Sonic Youth is the fundamental (rockist) fantasy which feeds their allure. [… W]hile punk annihilated prog after a mere half a decade of flatulent complacency, Sonic Youth are still lauded as countercultural heroes even though they have been making variations on the same record for over twenty years now.”

That parenthetical reference to rockism is important. One of the most notable tells that Sonic Youth isn’t actually as cutting-edge as their rep insists they are is their slightly sniffy insistence on their status as a guitar band, with the implication that eschewing synthesizers and samplers and drum machines earns them a kind of ascetic authenticity. Rockist assumptions overshadow much of the alternative era, and with the passage of time the critical attention that was lavished on Sonic Youth and the many flannel-clad guitar-slingers with hair in their eyes who followed them begins to look like a bigger and bigger mistake, especially in light of the less-publicized but massively more forward-looking trends that were then underway in, say, US hip-hop, or UK drum-and-bass.

And, hell, I even resent SY and their alt-rock fellow-travelers for sucking oxygen away from more interesting musicians who weren’t making particularly trailblazing records. As I was writing this, it unexpectedly occurred to me that the main functional differences between Sonic Youth and, say, Shawn Colvin—who was afloat in the same postpunk downtown NYC milieu at the same time, using similar nutty Joni Mitchell tunings—are a lack of volume on Colvin’s part and a lack of sincerity on SY’s. Chris Whitley was doing comparably wild guitar stuff then too, very consciously channeling East-Village-style no wave through a Bentonia blues idiom; after his first album was a big hit, he chose to run straight at the alt-rockers on his sophomore release, immediately alienating his nascent fanbase and blowing up his career. I bet we can all come up with our own lists of artists who were doing their most ambitious and risky work in the early ’90s—mine includes Los Lobos, American Music Club, even fucking Sting—only to see that work come and go with minimal attentive analysis while the music scribes of the Anglophone world pursued Perry Farrell across the grounds of Lollapalooza.

Much of this neglect is attributable to the credulous or cynical herd mentality of music-mag and arts-section editors, but in Sonic Youth’s case there’s also evidence of the band carefully shoring up their cutting-edge credentials in order to keep turning reviewers’ heads. Between albums for DGC they continued to sit in with all manner of free-improv groups all over the world, and in 1999, not long after The Wire granted them their first record-of-the-year award, they released Goodbye 20th Century, a sort of covers album consisting of pieces by avant-garde composers whom they claimed as influences, John Cage, Steve Reich, Yoko Ono, and Cornelius Cardew among them.

All that activity certainly signified copious hipness, and it did not go unappreciated by those who were meant to appreciate it. It also amounted to a fatuous mishmash of citations that are irreconcilable in ideological and even practical terms. People who know only one thing about SY’s early benefactor Glenn Branca, for instance, probably know that Cage forcefully criticized his music, more or less condemning it as fascist. Contrary to popular caricatures, Cage also strongly discouraged improvisation, believing that it encourages musicians to play what they’re most comfortable playing rather than listening and making new discoveries. Cardew was a committed communist who characterized punk rock as politically reactionary in terms that certainly would not have left Sonic Youth unscathed.

And yeah, sure, sometimes breakthroughs result from reconciling apparently contradictory ideas. But SY weren’t reconciling any contradictions. They were just ignoring them, engaging with avant-garde precursors on a superficial level, putting them to use as ornaments and signifiers while displaying no real understanding of—or much of an interest in understanding—the problems and aspirations that had prompted their novel approaches in the first place. Cool, of course, is permanent, and is therefore not super-interested in solving problems or achieving goals.

In Confusion Is Next, Foege quotes SY’s old Village Voice sparring partner Robert Christgau on the topic of the band’s experimental affectations: “My basic view of the avant-garde is that it’s where interesting ideas get started but aren’t necessarily brought to fruition,” he says. “Bands think other bands are important because those people are working on little details of ideas that also concern them.” That, alas, is not incorrect, and it serves as a decent summary of Sonic Youth’s working methods.

It is also very precisely how capitalist recuperation works. Whenever a few visionary people come up with expressive gestures that challenge existing systems or suggest transcendent alternatives to them, those systems react defensively, not by suppressing those gestures—that’s amateur-hour stuff—but by defusing them, detaching them from their assumptions and implications, and repurposing them to reinforce the very authority that keeps the systems in place. The call to action that those gestures once constituted vanishes, along with the memory of it, while the feeling that that call sparked remains, allowing and encouraging us to revisit it as nostalgic consumers. The systems don’t have to dispatch secret police to accomplish this, only to offer incentives and wait for somebody to show up and do the work. And somebody always shows up. Sometimes the record label even gives them points on the sales of the other artists they recruit.

In Girl in a Band, Gordon writes glumly of the transformation that Sonic Youth’s home city has undergone in the years since she first arrived. “In 1980 New York was near bankruptcy, with garbage strikes every month, it seemed, and a crumbly, weedy infrastructure,” she says. “These days, it gleams and towers in ways most people I know hate and can’t understand. […] It now feels more like a cartoon than anything real. But New York has never been ideal, and people have always complained sourly about the changing face of the city, the loss of authenticity.”

As ever, Gordon is able to retreat from the concerns that she’s just raised in the direction of apolitical and ahistorical cool—hey, y’know, people have always complained, it’s always been like this—but I think the words “can’t understand” are doing quite a bit of work in that passage. Today New York is the way New York is for a lot of reasons, but the professionalization of its ostensible avant-gardes and their acquiescent abdication in favor of shitty simulacra certainly belong somewhere on the list. And Gordon and her bandmates own a piece of that.

In a 1994 profile in The Wire—one that ran roughly contemporaneously with the release of “Bull in the Heather” and Experimental Jet Set; the first of several instances when SY made the cover of the magazine—Ranaldo gives the interviewer a recap of the band’s many recent collaborative rendezvous with musicians and artists from multiple unfailingly hip creative sectors across the globe. “Either we have a broad range of interests,” Ranaldo explains in a moment of admirable candor, “or we’re dilettantes.”

The beauty of being in Sonic Youth is that you never have to choose.

Martin Seay’s debut novel The Mirror Thief was published by Melville House in 2016. Originally from Texas, he lives in Chicago with his spouse, the writer Kathleen Rooney.