first round

(5) Shakira, “Hips Don't Lie”

bent

(12) Spoon, “I Turn My Camera On”

148-82

and will play in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the song/essay with the most votes at the end of the game. If there is a tie, we will play a one-hour overtime (and repeat until we have a winner). Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/4/24.

Authenticity and Shame in the Time of Shakira: sara sams on “hips don’t lie”

lleva, llévame en tu bicicleta

Like any good obsessive pop star fan, I can easily connect almost all of my important life stages to whatever Shakira song was most popular on the radio at the time. In 2017, I was preparing for a move from Spain back to the US following the death of my father, and “Bicicleta” was everywhere. It’s a cutesy, infectious song with a good-humored back-and-forth between Carlos Vives, a Colombian singer songwriter, and Shakira, who he hails as the “girl of the zone” in the song. Take me, take me on your bicycle. I think it’s a cousin to the Queen song in that the music somehow mimics the feeling of wind in your hair, and I didn’t mind that it was following me everywhere, reminding me that joy was still possible.

When I play the song today, I can remember sitting near the beach in Barcelona, watching two friends ride rented city bikes. When I gushed to them about how they appeared to be living the “Bicicleta” dream, one of them reminded me, sweetly, that the song is really a love song for Colombia. When you show Piqué [1] Tayrona [National Park in Columbia], he won’t want to go back to Barcelona. Later that night, we talked about the plagiarism allegations against Shakira, and my soul spasmed. I wanted to unsee some of the YouTube proof they showed me. Ok, sure, “Waka Waka” seemed an obvious steal, but “Hips Don’t Lie”? My subconscious began spinning with a defense of the songwriter.

Seven years later, I’m still trying to figure out why I care so much about Shakira’s artistic integrity.

viajé de Barein hasta Beirut/ fui desde el norte hasta el Polo Sur

In 2005, Philadelphia Inquirer’s Dan DeLuca described Shakira’s music as a “mongrel mix,” praising her ability to incorporate influences from her parents’ different cultural backgrounds— let’s pause to draw one line from Colombia to New York to Lebanon, and then another from Colombia to Cataluña. He also credits her mix for blending qualities from distinct popular genres; he mentions, among others, Metallica and Alanis Morisette. (No wonder I fell for her.) While “mongrel” leaves a bad taste in my mouth, I do like DeLuca’s honest review of Oral Fixation, Vol. 2: “But Shakira’s fervid persona and anything-goes aesthetic— mariachi horns here, a children’s chorus there— makes everything her own. And she’s always nervy, to say the least….”

Shakira’s combined “anything-goes aesthetic” and nerve has raised a lot of eyebrows since then. People lost their shit when she died her hair blond, and while I find it annoying that every female artist gets so closely scrutinized for her hair color, I also understand how easy it must have been to read “blond” as metonymy, a stand-in for Shakira’s “increasingly commercialized (read: anglicized) image” (Oxford Reference). [2] Of course, that’s an image we’re all familiar with by now; we’re savvy to Shakira’s savviness, her ability not only as a singer-songwriter but also as a marketer of global music. I have no grounds from which to make the following claim, but I can imagine her and Piqué conspiring behind the scenes about how much money a good breakup song would make, about how best to play up the sour mood for the press. [3] Her “I” is always a supposed “I,” after all—and DeLuca had it right when he spoke about her lyrical persona using the poet’s terminology.

It’s fairly easy to investigate the succession of artistic inspiration these days. Shakira co-wrote “Hips Don’t Lie” with Wyclef Jean, a song that is overtly in conversation with Jean’s own “Dance Like This,” a song which (again, rather overtly) sampled the salsero Jerry Rivera’s trumpet trill. So should Shakira have also credited Rivera? Or is there some transitive-property kind of understanding, a breadcrumb trail that’s so clear that outright crediting Rivera becomes unnecessary? I’m not asking about what Shakira should or shouldn’t have done legally—the lawyers determine right or wrong when it comes down to money, and it always comes down to money with Shakira, because she’s a woman who makes a lot of it.

Morally speaking: It must have been like an open secret, right? I mean, was there any way that no one would ever trace that musical phrase to its earlier appearances? The way the brass announced itself so unabashedly, with leaping notes of prowess, in so many rooms, in so many cities, in so many countries, for months on end? Maybe in a 2005 world, when YouTube was a rabbit hole you had to go down on purpose? I’m not asking you, not really. I am asking myself: Does she need forgiveness? Why do I need to forgive her, for me? Is it because I’ve romanticized what music critic Lopez refers to as her transnational identity (in “Ojos Así,” she brags, I’ve traveled from Bahrain to Beirut), and that romanticization is key to my own self-conceptualization? Or is it because the attacks on Shakira so often feel like they’re part of a larger problem?

Accusing Shakira of plagiarizing his trumpet arrangement, Rivera called Shakira “indecent.”

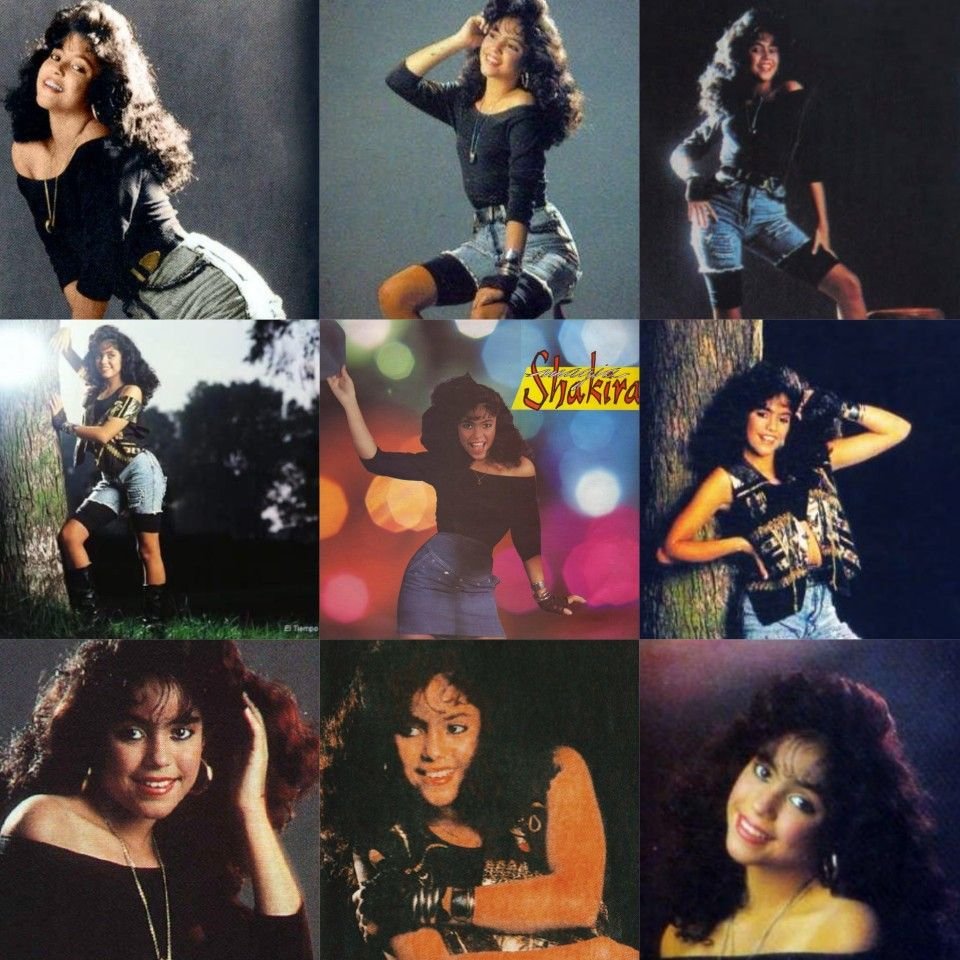

Her hair might lie, says another news anchor, after watching a video of the brunette Shakira at age 13, but her dance moves sure don’t.

From Shakira’s Magia, 1991

cada vez que se aparece frente/ a mí tu anatomía

When I was thirteen, Shakira released Donde Estan Los Ladrones (1998). I was wearing too-tight t-shirts my mother shouldn’t have bought me from a store ridiculously called Bebe, and I discovered Shakira on my Discman on a bus ride home from a Spanish field trip. To this day, I thank you, Jasmine, for letting me listen. Jasmine and I were both white girls who excelled in Spanish class, although I think she had tenable experience with a Spanish-speaking culture, whereas I just had what felt like a “really special relationship” with the language. I’d been educated in a bilingual elementary program, so I spoke Spanish somewhat fluently, and it was a language that, at home, felt like something I could keep all to myself. Linguistic doors opened up to universes I could enter, places I could go where most of the people in my life couldn’t follow me.

In those teenage bedrooms parallel to the real one I inhabited in suburban east Tennessee, I heard Shakira express what a local preacher might call “my innermost thoughts and desires.” And she was doing it in a way that somehow didn’t feel at odds with the evangelical cultural soup I was swimming in. Part of this magic likely had to do with my doubtful translations. What does it mean to say sin ti el mundo ya me da igual—“I could give a damn if you leave me,” or “I could give or take the world without you?” I chose the latter but I also heard hints of the former in her voice, and the cognitive dissonance was thrilling.

But another part of the reason why Shakira has—and has always—had this special way of speaking to me through her music is that her personas always seem to know how to toe the line between “sexualized” and “sexual,” between desirable and free to desire: I run out of arguments every time I see your anatomy, she sings, in “Ciega, Sordomuda.” As if she had a good-girl list of reasons not to act on her desires, which she could finally discard. Finally outside of the realm of reason, she didn’t need to worry about, well, giving herself consent.

Of course I don’t know what Shakira’s life has really been like, and I can’t speak to Colombian culture even a little. I knew far less in high school. But as a young girl going through puberty, I could tell that Shakira’s personas lived in a world where to be a loveable woman meant to try and bank on your sex appeal, all while being coy enough to pretend you had none. One needed to be both sexy and pure, somehow, and this required logical acrobatics—and quite a bit of self-denial (enough to drive one mad, blind, dumb).

Surrounded by Baptist churches and peer-pressured into Young Life, such a world was familiar to me. I was taught at summer camp, for instance, that masturbation was a sin, though it was clearly somehow also funny if you were a dude. It was not funny if you were a girl.

One high school boyfriend, in response to my fierce jealousy (I’m as good at jealous as I am at shame), differentiated me from a pretty girl in my grade by explaining to me that I was the sexiest, and she was the cutest. That is a contest you just can’t rig, I thought at the time.

And it was a contest I could hear Shakira mocking. Her personas all seem to know that the men around her wanted a woman to say: hey, I will make you meals for free and blow your mind in bed, if only you stay faithful. Which, I’d argue, translates to, I will do your chores and you because I love you so much, and all you have to do is try to love me in return. Song-Shakiras usually recognize the absurdity of the patriarchal romance scheme. But they also recognize that understanding the absurdity doesn’t preclude one’s desire to be wanted in the first place.

so keep on reading the signs of my body

Two questions come up for me, at this point, and they both have to do with sexuality and authenticity.

If sexual desire is a cultural phenomenon, how can a girl entering puberty in a patriarchal (and evangelical) society learn how to “read the signs” of her body without first translating them, in her mind, for an audience?

If a female pop star is bound to be scrutinized for her sexual appeal, how can she reclaim agency while embracing the performativity necessary for market success? How can she balance her desirability with her personas’ open embrace of desire, along with all of the other “uglier” emotions that come with those wants?

“My Hips Don’t Lie” is a game of tension and release, lyrically and musically. When Shakira lauds “the attraction, the tension” as “perfection,” of course she’s singing explicitly about sexual tension (we’re doing this dance perfectly together), but I think she’s also singing about the tension of sexuality that she has experienced in a global, euro-centric, patriarchal market. It’s not just that she walks the line perfectly between being sexualized, objectified and confident, powerful: It’s almost as if is trying to draw the line, here, herself.

In her essay on the “My Hips Don’t Lie” music video, popular culture critic Anamaria Tamayo Duque writes: “Clearly, dance is the medium to get noticed and to establish some kind of agency and presence.” Her main argument is that Shakira purposefully manipulates the settings, costumes, and expressions of self in the video to represent different versions of corporeal identity. These different versions of self appeal to her vastly different global audiences—those in Barranquilla, Colombia, who felt betrayed by her international stardom; the Haitian and Colombian diasporas, as well as the larger Latino immigrant communities in the US; a euro-centric audience that would necessarily read the other presentations as “wild” and … and finally, a fourth “presentation,” that slides comfortably and easily between all of the former, holding the tension with ease.

And it’s that last presentation that I think I found so compelling as a young white woman, who had inherited euro-centric notions of beauty— and the patriarchal Christian enforcement of what a woman should and shouldn’t do with the scraps of sexual power I was allotted, literally, in my flesh.

si te vas, y me cambias/ Por esa bruja, pedazo de cuero

“Hips Don’t Lie” was released the semester I turned twenty-one, and I was studying abroad in Madrid. Stalking my former self, I realize that I named a quaint 2005-era Facebook album “Te Dejo Madrid <3,” complete with a smarmy emoji heart, after the only Spanish song on Laundry Service (of “Wherever, Whenever” fame). The collection features very few photos of the city, and rather a lot of my blurry face. I remember the digital Canon I would put in the clutch I’d take with me to the discotecas, how it would barely fit next to the compact powder and chunky international cell phone and the birth control pills. I’d have to be careful when opening the clutch in the disgusting bathrooms with their infinity mirrors, the beat to whatever electronic DJ set thumping in my throat.

When I could stand to examine myself in the harsh light, I could have also noted that I had: great hair, even when it was covered in sweat; what I never understood to be a flawless hourglass figure; and a smattering of hormonal acne on my cheeks. But when “My Hips Don’t Lie” came on, I wasn’t me or any of those rateable attributes, I was pure adrenaline, an unstoppable feminine goddess, doing whatever the fuck I wanted to do on the dance floor. Nothing about the way I moved was inauthentic. I’d throw my gorgeous hair back and move my shoulders in a groovy elliptical; my hips would follow suit. I didn’t need a man to see me to feel sexy; I was following my own wants. Drink, dance, love thyself. Shakira’s directives— Be wise, and keep on— seemed to open a portal into a shame-free dimension for me.

*

I will never forget a romantic rival in high school dissing me publically for my oily skin. To this day, I often lead with this descriptor of myself. I’m in my late thirties and I live my life in a desert with severely cracked ankles. But when I’m talking to cosmetic representatives, girls who want my money but who otherwise have no reason to try and ruin my “reputation,” I can hear Angela’s voice come out of my mouth as I say “my skin is just so oily.” Angela. What was her last name? There’s a special level in hell for women who are cruel to other women, Shakira said in a recent interview. And yet, her personas so often unabashedly diss her romantic rivals—Shakira is doing the same thing, in that very interview—, and they have done so, all the way back to Pies Descalzos and “No Te Vas,” a song in which she bitterly disregards her sexual competition as a pedazo de cuero. I have to hand it to Colombian slang: old leather is a vividly putrid way of describing a vagina that has gotten around.

God, I love that song, and I especially love that angry break in her voice, if you exchange me for that witch. If women share an unspoken covenant to protect each other from the shame game, we break that covenant too often: Angela, Shakira, and me, too. While I was always too scared/ ashamed to have sex, I could be awarded a special prize for the amount of friends’ crushes that I’ve kissed. I used to acknowledge this, at least a little, by describing myself, remorsefully, as a “horrible flirt.” A roommate in my early twenties joked about what she called my handful of “Christian sleepovers”; she was describing my special art of seduction that was unabashedly sexual but that also made it clear there would be no actual sex. Looking back at those years, at me groping through those discotecas, I can see that I was trying to rake in the ability to feel desire by attempting to collect others’.

In the long run, it didn’t work.

When I met my now husband, his insatiable desire for me gave me a high I thought I wasn’t capable of experiencing, one that had belonged to a version of me that had lived only fully in the dark corners on the dance floor. It’s hard to admit, but before him, I’d never felt and acted on my lust, fully, before—never acted without stopping myself, that is, either physically, by abruptly ending a sexual encounter, or mentally, by dissociating. And I only “went for it” with him because—why? I always say that I loved him from first sight, and I know that sounds straight out of a Shakira song (I am waiting for you, seated on the corner of forever), but it’s not a lie. Also, he had—has—this way of wanting all of me, and of sharing his want in a way that doesn’t make me try desperately to imagine myself being wanted from afar—like a star in a music video. Although admittedly, that is a game I still have to play with myself, sometimes.

no fighting

I took the clamshell of pills with me everywhere I went because they were supposed to help me with my acne and I didn’t want to miss a dose if I stayed out all night. I wasn’t having sex in Madrid, I just wanted to look like someone who was. I wanted the full power of my sexuality without any of the consequences. I wanted what one critic deemed Shakira’s personal brand of “innocent sensuality,” and I wanted it so badly that I dressed up as her for Halloween. More specifically, I dressed up as her hips, pinning a piece of computer paper to my skirt (which was indeed a scarf), saying something like, “I hereby certify the veracity of these hips.” I hope it was bilingual.

Wyclef Jean’s infamous “no fighting” throwaway lines are self-sampled—a cocky show of prowess—girls, don’t fight over me! Then quoting himself, “Girls, don’t fight over me!”The arrogance is infectious and reads with as much humor as it does pride. But the confidence of “Hips Don’t Lie” feels to me the most overwhelming tone, and I always took the command somewhat seriously: Do Not Pick Apart These Lyrics. The World’s a Dumpster Fire But This Song is Great. We’re Not Down, We’re Up. Just Move Your Hips. They’re Not Fuckin’ Around, Are They? No One Here is Trying to Steal Your Man. And so on, for a glorious three minutes and thirty-eight seconds.

With “Hips Don’t Lie” as my anthem that fall of 2005—how could it not have been; it was everywhere—the dance floors in Madrid felt like pure potential. This, I think, is what a good dance song should do to any of us—to all of us: take us out of our doldrums into an unadulterable euphoria, even if for only three minutes and thirty-eight seconds. As Duque puts it, “the lyrics emphasize the power of the body to convey the truth and assert her presence in a space,” something that, if a bit hard to explain, is something I think we can all recognize needing.

there’s nothing left to fear

I know that many singer-songwriters and pop stars before and since Shakira have entered their own answers to the unsolvable problems I’m bringing up here. I’m interested in Shakira specifically because of how she spoke to me in the dark; she found me first as an awkward, overly sexualized and scrutinized thirteen-year old (she's a perfect girl— she has perfect tits and a perfect ass, someone said of me in eighth grade), and she stayed with me through early adulthood. In the early 2000’s, when romcoms like Old School still pitted women you could marry against hotties wrestling in KY Jelly, Shakira in my car, on my iPod, at the club, was a balm.

I remembered that balm when I was preparing to give birth to my daughter in 2020: I made a playlist called “Strength" that ended up being 85% Shakira. It included her tongue-in-cheek “She Wolf”—“let her out!”; “Ciega Sordomuda,” with its own signature trumpet blazing, brass-ing her strength into my veins—if there’s one thing I won’t ever stop doing, it’s loving you; and of course, “My Hips Don’t Lie,” because if there’s anything I inherited from the women in my family, it was certainly good birthing hips.

And isn’t that something else Shakira is saying to us in “Hips Don’t Lie,” too?

Dudes can deify women's bodies. They can certainly shame them, attempt to control them via that shame, and they can definitively control them via (shameful & immoral) legislation—but all of those powers seem like a farce when you compare them to what women do: conceive, grow, and birth every human on the planet. Not a balm exactly, but it isn't a lie, either. Duque concludes her argument, giving me chills:

Shakira states over and over in the song that she has the truth, the authenticity, in her exotic body, and specifically in her hips. Even though this may be the claim of the song, it is not an issue of truth or authenticity because, if Shakira’s dancing body is the place of fluidity and multiplicity, it cannot be labeled authentic or true to anything. It will never be constructed as authentic but as continually shifting and ambiguous. Let us then keep on reading the signs of her body.

Shakira’s signature sensuality might be an impossible illusion, something her female fans will never be able to perform; but at least it gave me an ideal to strive toward that allowed a little room for myself. If I can see more clearly now, approaching my forties, and as mother of a mixed-race daughter, that I don’t want to be walking that line at all, I feel like I can thank her a little bit for that, too.

Citations

Cepeda, María Elena. "Shakira." The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States: Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference.

Deluca, Dan. “Shakira’s World.” The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Duque, Anamaria Tamayo. “Body, Space, and Authenticity in Shakira’s Video for ‘My Hips Don’t Lie,’” The Routledge Companion to Global Popular Culture.

Lopez, Daniela Guitérrez. “(Dis)identifying with Shakira’s Global Body: A Path toward Rhythmic Affiliations beyond the Dichotomous Nation/Diaspora.” Race and Cultural Practice in Popular Culture, edited by Domino Renee Perez and Rachel González-Martin, Rutgers University Press, 2018, 152-174.

notes

[1] Shakira’s now ex-husband, a famous Barcelona football player

[2] In Lopez’s article on Shakira’s transnational identity, she notes that it wasn’t just the hair: Pre-Blond Shakira’s music was more outspokenly political, and after 1998, “Shakira became blond permanently…Through makeup (contouring) and lighting tricks that altered her skin tone, showcasing a paler hue, her features appeared slimmer….further accommodating Euro-American standards of beauty…”

[3] If you need a primer on the relationship gossip, and the way the press talks about Shakira always in the same breath as shame/shade, here’s this from a People article: “But despite their efforts to remain under the radar, the couple made headlines after Shakira seemingly shaded their relationship in two songs, "BZRP Music Session #53" and "TQG."”

Sara Sams is a writer and translator from Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Her first book of poems, Atom City, is about growing up in the Manhattan Project town and the militarization of science that made creating the atomic bomb possible. When she wants to dance away her lifelong grief about the former, she often turns to Shakira. She lives in Tucson with her family and teaches at the University of Arizona. You can find more of her creative work at saraesams.com.

peter mcdade on spoon’s “i turn my camera on”

I can’t remember exactly when I gave up on the idea of being a good dancer, but it was early in life. If someone had managed to capture the moment in a photo, perhaps a faded Instant Polaroid, it would probably show a confused young me in third or fourth grade, hands awkwardly clutched by an enthusiastic teacher or nervous looking young girl, my left leg undercutting my right in a way that makes it clear I am about to hit the ground. Or maybe it’s a snapshot from middle school, when sadistic P.E. teachers decided to make square dancing a two-week unit. Shouting commands at me, while my feet struggled to keep from stepping on the Mary Janes of the unlucky girl I was partnered with, was not the best way to increase my confidence.

I was a shy child. I was a child whose body often felt like someone else’s. These are not ideal conditions for dancing.

I started playing the drums around the time of those theoretical snapshots. I’d discovered my love for music when I borrowed my sister’s copy of The Beatles’ Red Album, and I tapped my way through my entire academic career, much to the annoyance of my teachers. The way that music moved, the ways that time could spin up or slow down or even come to a halt inside the rhythms and melodies, made much more sense to me from behind the cover of a drum set; I can see the music as well as hear it, when I am playing the drums. Now, after fifty years of playing, on my best days I think I’m a good drummer, but I still dance the way I did when I was ten—arms and legs akimbo, each limb somehow moving at different tempos. Oh, I can hear the the groove in a good piece of music, and I can feel the groove and I can play the groove, but take me out from behind a drum set, stand me up, and ask me to move to the groove? Then I need help. A lot of help.

But here’s the thing: even after I gave up on the idea of being a good dancer, I did not give up on dancing. I think everyone likes to dance, even people who say they don’t. Society only allows us to move in a limited number of ways, most of the time, our everyday actions controlled by one of those old Atari joysticks with a limited number of options. Once we start dancing the possibilities increase exponentially. Moves that would be frowned upon in most circumstances are suddenly allowed, even encouraged. Hold your nose and pretend to dive underwater? Sure! Move like a robot, or a worm on the floor? Why not!

What is a good dance song, then? My needs are few but non-negotiable. I want clear instructions, in the form of sonic clues, about ways my body should move in order to match the specific groove of this specific song, and I want those instructions as quickly as possible. When a good dance song begins, the whole crowd will instinctively move as if they have known it their whole lives, even if they have never heard it before. When a good dance song begins, this movement comes easily not just to the natural dancers, the people who dance even when there is no music, but also to me, the poorly dancing drummer doing his best to maintain his balance.

Which is what makes “I Turn My Camera On” such a damn good dance song. It’s written and performed by Spoon, indie rock darlings from Austin who I have loved for many years now, even if my husband fell asleep during one of their concerts. Yes, our first kid had just been born, so we weren’t sleeping much, but his power nap is admittedly a sign that the band is not embraced by everyone. I love the minimalism I hear in their best songs, a sense that every unnecessary sound has been erased, even as they build great melodies around jagged rhythms.

As much as I adore Spoon, I would not have expected them to write one of my favorite dance songs. A good dance groove can really shine when given some space to breathe, though, and that is something the band has always excelled at. The best dance grooves also benefit from a great drummer, ideally one who ignores flash in order to better serve the song, and that’s something else Spoon has.

“Camera” was released ahead of the band’s fifth album, Gimme Fiction. By this point I was the kind of fan who listened to every new song as soon as I heard about it, and I downloaded “Camera” the day it dropped. It was thrilling to hear the Spoon sound I loved on top of a classic dance beat. I was doing the musician’s head bob within seconds, and how could I not? The first eight bars provide an easy-to-read map for my body to follow, in the clear language of the musical stars of the song, the drums and the bass.

That is exactly how it should be, of course. Some things in life are best not overthought: coffee should be strong but not bitter, spring and fall are the best seasons, and when it comes to a dance song, the bass and the drums should climb in the front seat to serve as driver and navigator. Their job is to get us there safely, to create the groove we must slide into if we want to move to this song. Oh, and they should work together in a way that doesn’t just make us want to move to the music. They should create such a groove that we have to move.

This is a good time to go and hit play, if you haven’t already. Listen to the way the bass melody carries the song, pushing the downbeat just enough to make the song feel faster than it really is. The bass drum hits on the one and three, with extra upbeat kicks at the end of every other bar to push us back to the start of that bass line. The guitar chords are stabbed, not strummed, adding a layer of tension―first on the two and the four, with the snare, and then on every downbeat, shadowing the bass. We’re rolling along at 100 beats per minute, a speed that lets you feel like you’re dancing, but also lets you feel confident that you can keep up with the music for however long it lasts. Just keep moving your feet in time to the bass, and you are, in fact, dancing.

The vocals come in at start of the ninth measure. Lead singer Britt Daniels’s falsetto immediately calls to my mind Prince, in case we were in any doubt that we are here to dance. Occasionally doubling the vocal, and adding background chants sung in a lower register, creates layers of voices that mimic the range of instruments, with the falsetto living in a sonic land near the guitars, and those lower voices hanging out with the bass and drums. And while there may be those who argue that lyrics do not matter in dance songs―that the groove is all, and the words just need to provide syllables for the vocal melody to ride on—my brain needs something to distract itself with, even when, or maybe especially when, my body is being ordered around by the groove.

“Camera” delivers here as well, with lyrics full of images that are as vivid as they are open to interpretation, starting with the opening line, which is also the song’s title. A dance song with a deep groove that’s all about being turned on: what could be better than that? What’s being turned on, though, is a camera. Turning a camera on means I am getting ready to watch, to study what is happening from a safe distance. A camera provides an excuse to stare, but also offers an excuse to not actually take part.

You can see why this would appeal to me. On the dance floor, trying not to be aware of how I look, I love the idea of having that camera between me and the action. People pose for the lens, so that’s what they see. The person behind the lens disappears. No one dancing but us cameras.

The other key line of the song, “It hit me like a tom,” creates an image that is as sonic as it is visual. As a drummer, I can think of a perfectly hit tom as a beautiful thing―even for the tom, as it rings out. A full sound. A satisfying action. Perhaps whatever our voyeur saw from behind the safety of his lens moved him more than he’d expected, sending a positive shiver through his body. It could also be that our narrator experienced this as a bad thing. Other lyrics point to this possibility: “You made me untouchable for life/And you wasn't polite.” I love being able to imagine multiple meanings drifting through the bodies drifting across the dance floor, the shared motion and disparate interpretations existing at the same time.

The final thing I need to know from a dance song is when it is ending. Once I work up the nerve to start dancing in front of others, the last thing I want is to be left moving awkwardly when the music stops. After the last full chorus in “Camera,” the guitar stabs grow more menacing and a new keyboard melody hovers in the distance, indicating change is approaching. The phrases “I turn my camera on” and “hit me like a tom” start to lap each other, the second line beginning before the first line finishes, creating the sensation that time is speeding up, even as my feet keep moving at the same pace. The vocals began to crack into pieces but the bass and drums keep relentlessly driving, accompanied by a new, unsettling sound effect, a noise that sounds more like an earthquake than music. Finally, the guitar chords find one more level of intensity for exactly two bars, the last of the eight emphatic jabs bringing the song to a sudden, and satisfying, stop.

Everyone brings their own histories to each piece of music they hear, and my baggage and childhood scars are not necessarily yours. But a song that I can find a way to dance to, not only surviving the experience but enjoying it, even using the experience to escape, for three-and-a-half minutes, the limitations of my own body? That is a song that should be able to loosen any body it comes into contact with, and I can think of few greater accomplishments.

As drummer for the rock band Uncle Green, Peter McDade spent fifteen years traveling the highways of America in a series of Ford vans. While the band searched for fame and a safe place to eat before a gig, he began writing short stories and novels. Uncle Green went into semi-retirement after four labels, seven records, and one name change; Peter went to Georgia State University and majored in History and English, eventually earning an MA in History. He published his first novel, The Weight of Sound, in 2017, and his second, Songs By Honeybird, in 2022, and released an accompanying soundtrack of original songs with each. He teaches history to college undergrads in Atlanta, and lives in Atlanta with his family.